Forest Hills Gardens

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Despite the medieval, Germanic appearance of the buildings, this town square isn't in Bavaria—it's in New York City. Forest Hills Gardens in Queens, N.Y., was begun in 1909, a project of the Russell Sage Foundation, which had been founded by the widow of a successful Wall Street financier. The planned community of 142 acres, which introduced the British Garden City movement to the United States, was intended to demonstrate the latest ideas in town planning, housing, open space, and building construction. It's pretty obvious that in the intervening years, Levittown, N.Y.—not Forest Hills—became the prototype for American planned communities. But in an age of diminishing resources and an interest in walkable neighborhoods, it is worth revisiting Forest Hills. One of the strengths of the Garden City movement was that it dealt with town planning in a comprehensive way, and this 100-year-old piece of New York City remains a model for how the attractions of town and suburbs can be combined.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The town square faces a station on the Long Island Railroad, which connects Forest Hills to Manhattan, 20 minutes away—an early example of transit-oriented development. The buildings on the square have stores and restaurants at street level and apartments above, just the sort of mixed-use that many developers are promoting today. The tallest building, nine stories, originally housed the Forest Hills Inn, since converted into condominiums. Apartment buildings line the streets immediately behind the square (right), creating a more urban density in this part of the community. As you walk away from Station Square, the scale of the buildings becomes smaller, there are more trees, and the surroundings are greener and more parklike.

-

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. Photograph by Jonathan Wallen © 2009 Jonathan Wallen.

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. Photograph by Jonathan Wallen © 2009 Jonathan Wallen.Walkability, which is the goal of most town planners today, requires smaller lots and more compact houses in order to keep distances short. In the housing terrace at right, 17-foot-wide town homes use land efficiently, but even detached house lots at Forest Hills can be as small as 2,800 square feet (compared with a typical suburban lot size today of 20,000 square feet). Forest Hills has a variety of single-family houses: attached, semidetached, and freestanding. The aim of having many housing types was partly to give more choices to buyers and partly to create the kind of visual variety found in old towns. This is very different from the sort of homogeneity that characterizes most modern suburbs. Notice also the generous planting strip next to the sidewalk, which gives the street trees plenty of room.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The planner of Forest Hills was Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (1870-1957), son of the famous landscape architect. Olmsted was in his 40s, highly experienced, and he produced one of the great garden suburb plans of this period—or of any period. He showed how, in a relatively small area, it was possible to combine a variety of housing: apartment buildings, housing groups, and individual houses surrounded by gardens. The plan is not a simple grid—the streets curve—but neither is it the mindless "spaghetti" of so many modern suburbs. There is a clear hierarchy of larger avenues (called greenways), streets, and narrow internal streets that resemble back lanes. There is also a variety of open spaces: a town square, a village green, small parks, and this landscaped circle at the heart of a quiet cluster of houses (right).

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.One housing group, intended for lower-income buyers, consists of attached houses only 13 feet wide. (The end houses, with octagonal bays, are wider.) The houses are constructed entirely of precast hollow-concrete slabs and panels. A single house consisted of 140 panels and could be assembled in nine days. The successful use of prefabricated concrete in housing at such an early date (1913) was decades ahead of what anyone else was doing in the United States or Europe. The lively exterior doesn't look cheap or mass-produced, despite the limitation of the standardized panels, which are given an attractive rough pebble finish. Equally impressive is the fact that this experiment has survived more than 90 years and is in excellent shape. This probably has something to do with the rather conservative design, which sticks to the tried-and-true: pitched roofs, protective overhangs, dormers, and traditional windows. And these little (1,960-square-foot) three-bedroom prefabs have more than held their value; one of these houses is currently on the market for $929,000.

-

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. Photograph by Jonathan Wallen © 2009 Jonathan Wallen.

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury. Photograph by Jonathan Wallen © 2009 Jonathan Wallen.The architect of the prefabricated houses, Station Square, and of many of the buildings at Forest Hills was Grosvenor Atterbury (1869-1956), the subject of a recent monograph. Atterbury is not well-known, but he deserves to be. He belonged to an in-between generation of architects, younger than turn-of-the-century giants like Charles McKim and Daniel Burnham and older than the first Modernists, such as Eliel Saarinen and George Howe. Atterbury worked in a variety of architectural styles—and for a variety of clients. At the same time as he was designing his ingenious precast concrete system for low-cost housing, he was building a group of cow barns in Newport, R.I. (right), to house the prize Guernsey herd of Arthur Curtiss James, one of the richest men in the country. So, a society architect or a revolutionary? Perhaps both.

-

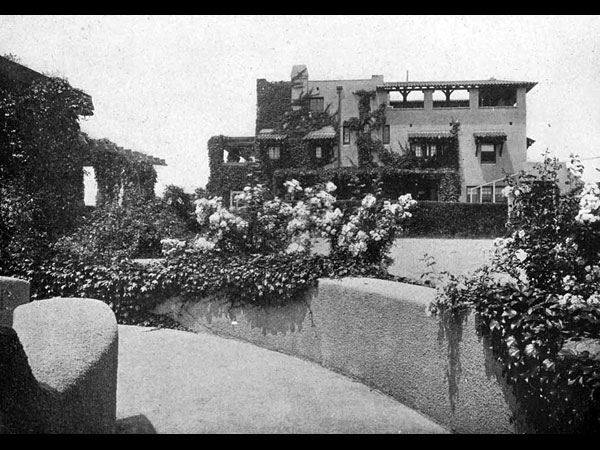

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury.

Photograph from CREDIT: The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury.One of Atterbury's first projects in concrete was a summer colony of 10 cottages, built in 1897 for sugar magnate Henry Osborne Havemeyer, at Bayberry Point on the south shore of Long Island. The houses were built out of cast-in-place concrete, but what is even more striking is that they have flat roofs and starkly unadorned surfaces, giving them the appearance of the Modernist villas that architects such as Viennese firebrand Adolf Loos ("ornament is a crime") would build some years later. Did Grosvenor Atterbury invent the International Style? Not exactly. The Bayberry Point houses, which were advertised as "creations of the fancy," were intended to recall the Moorish architecture of North Africa, which Atterbury and his collaborator, Louis Comfort Tiffany, had both recently visited. Still, it is a curious fact that these two American eclectics arrived at bare concrete construction a decade before the European avant-garde.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.There is nothing bare about Forest Hills—quite the opposite. The picturesque architecture of medieval towns was greatly admired by garden city architects, and Atterbury gave the buildings around Station Square a medieval air, using precast concrete to suggest half-timbering. Decorative fretwork and patterned brick complete the effect. One is tempted to see this as an early example of architectural theming, except that it is done with such conviction and inventiveness that it is more like a performance than a simulation.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.What makes Forest Hills different from—and much better than—most modern suburbs is not just the density, walkability, and architectural variety. It is also the attention to detail, whether in Olmsted's planting strips or Atterbury's distinctive street lamps. The designers understood that one of the great challenges of building a planned community from scratch is creating an instant sense of belonging. They achieved this by harmoniously integrating planning, landscaping, and architecture. That may be Forest Hills' most important lesson: Community building is an art. Not a pictorial art, but an experiential one, appreciated when you walk through the dark arcades of Station Square, beside the shaded town green (where a person sat in a deck chair the day I was there) and along the looping curve of Olmsted's greenway. This is not merely planning or building; it is place-making.