Detroit's Beautiful Ruins

-

Photograph by Shawn Wilson, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 1.0.

Photograph by Shawn Wilson, via Wikipedia. This image is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 1.0.From my hotel room in Windsor, Canada, the skyline of downtown Detroit actually looked pretty: the skyscrapers—old and new (Philip Johnson's neo-Gothic Comerica Tower is in the center)—the broad Detroit River, a cruise ship moored at a waterfront park, and an elevated train,* the People Mover, periodically tootling through the scene. An orderly, neat thriving city, one might say. One would be wrong.

Correction, April 16, 2009: The piece originally stated incorrectly that the People Mover is a monorail.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The day before I arrived, the frozen body of a man was found in the elevator shaft of an abandoned warehouse; only the feet were visible, the rest of the body being entirely encased in ice. The homeless men living in the warehouse, treating the corpse as unremarkable, ignored it for a month.* (It was later determined that the man died from a cocaine overdose.) The warehouse is next door to one of Detroit's most fabulous ruins, Michigan Central Station (right). The railroad terminal and the attached 18-story office building, which opened in 1914 and have stood empty since 1988, are the work of New York architects Warren & Wetmore, who also designed Grand Central terminal and the New York Yacht Club on 44th Street.

*Correction, April 3, 2009: The piece originally misstated that when the body was finally discovered by a journalist, who called 911, it took police two days to arrive on the scene. While Detroit police were initially criticized for a tardy response, police records show they arrived promptly on the scene after the 911 call.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Empty buildings are not unusual in the Rust Belt. Cities like Cleveland and Indianapolis, for example, have many abandoned factories, breweries, and industrial buildings—so do Philadelphia and Baltimore. What makes Detroit unusual is that there are so many of these abandoned hulks, that they are so large, and that they are generally surrounded by open land, since their neighbors have long since been demolished. The result is a curiously suburban landscape.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Between 1910 and 1920, Detroit doubled in size and became America's fourth-largest city. Thanks to the auto industry, it was a prosperous place, which is evident in the quality of the architecture. When the city of Highland Park, where Ford built the first assembly line, needed a library, for example, it commissioned New Yorker Edward Lippincott Tilton, who built libraries in Washington, D.C.; Wilmington, Del.; Springfield, Mass.; and Manchester, N.H. Tilton apprenticed with McKim, Mead, & White and trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and in most cities, his delicate brand of American Renaissance would be considered an architectural treasure; this building has been boarded up since 2002.

-

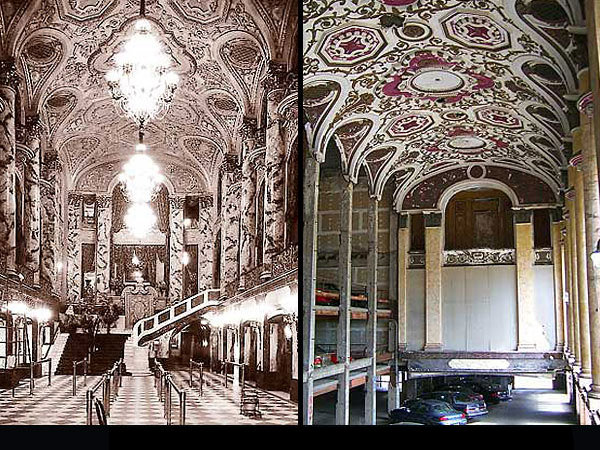

Photographs uploaded to Wikipedia by Gsgeorge. Images licensed under GNU Free Documentation, Version 1.2.

Photographs uploaded to Wikipedia by Gsgeorge. Images licensed under GNU Free Documentation, Version 1.2.Perhaps the most bizarre ruin in Detroit is the Michigan Theater, designed in 1926 by Rapp & Rapp, a Chicago architectural firm that specialized in theaters and movie palaces and built the globe-topped Paramount Building on Times Square. The Paramount originally included a 3,600-seat theater, later turned into office space. The Michigan Theater was converted, too … into a parking garage. I was chased out of the building by a scolding security guard, but not before seeing the lines of cars anomalously parked beneath a richly decorated plaster-relief ceiling.

-

Photograph by Jeff Haynes/AFP/Getty Images.

Photograph by Jeff Haynes/AFP/Getty Images.Detroit's residential neighborhoods are likewise distinguished by the quality of their homes, the numbers of vacant lots, and especially by the intimate adjacency of abandoned, empty, and often burned-out houses and inhabited dwellings. It's like Berlin or Warsaw in 1945. Just as in post-World War II photos of those ruined cities, the most shocking thing is to see people carrying on their everyday lives in the midst of so much physical destruction.

-

Photograph from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Photograph from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.Another striking building (this one still occupied) is the original General Motors headquarters building, designed in 1919-23 by Detroit's premier architect, German-born Albert Kahn. Kahn, who pioneered the use of reinforced concrete construction in assembly plants for Packard and Ford, and even built industrial buildings in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, was considered a pioneer of Modernism by European architects. But only Kahn's factories look like factories. The massive GM Building exhibits the relentless planning logic of a Bauhausler, but it is executed with all the delicacy of Kahn's friend Henry Bacon, who designed the Lincoln Memorial.

-

Photograph by Mike Russell via Wikipedia. Image licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0.

Photograph by Mike Russell via Wikipedia. Image licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0.Kahn's premier work in Detroit is undoubtedly the Fisher Building, a 30-story downtown office tower built in 1928 in the stripped-down American Art Deco style that was popular at the time. As Raymond Hood would do at Rockefeller Center, Kahn emphasized the vertical thrust of the building and made it stylish, ornamented, and entirely modern all at once.

Correction, March 18, 2009: This article originally misspelled the name of the Fisher Building.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Perhaps the oddest thing about the ruins of Detroit is that they are so close to downtown, and downtown Detroit is not so different from many other Midwestern cities: a mixture of solid buildings from the 1920s, utilitarian steel-and-glass towers from a later era, parking garages (since all the office workers live in the suburbs). The omnipresent Renaissance Center, still the tallest building in the city, is a weird sci-fi outer-galactic space colony designed by John Portman in the 1970s. There are even a few reminders of the old days, like Jacoby's "German Biergarten since 1904," where I had lunch. Its fuggy, convivial atmosphere was a reminder of the big city this once had been.

-

Rendering courtesy Doubletree Hotels.

Rendering courtesy Doubletree Hotels.Detroit is not disappearing anytime soon. At 1.03 million residents, it is the 11th-largest city in the country, larger than San Francisco, Boston, or Seattle. The current downturn in the fortunes of the automobile industry is a hard blow, of course, and it's difficult to be sanguine about a comeback for the city, unless you are the sort of urban booster who sees the construction of casinos as a harbinger of urban renaissance—I'm not. On the other hand, some of the large empty downtown buildings are being refurbished, like the old Fort Shelby Hotel (right), a 1916 building, with a high-rise extension by Kahn, which was reopened last year after standing empty for 30 years. Also, here and there, one sees smaller examples of urban enterprise: a renovated storefront, a club, a restaurant. Not exactly a hotbed of the creative class (which prefers warm climates, anyway) but something. If cities were movie characters, Detroit would be Mickey Rourke's Randy "The Ram" Robinson. Down, but not out.