Back to the Drawing Board

-

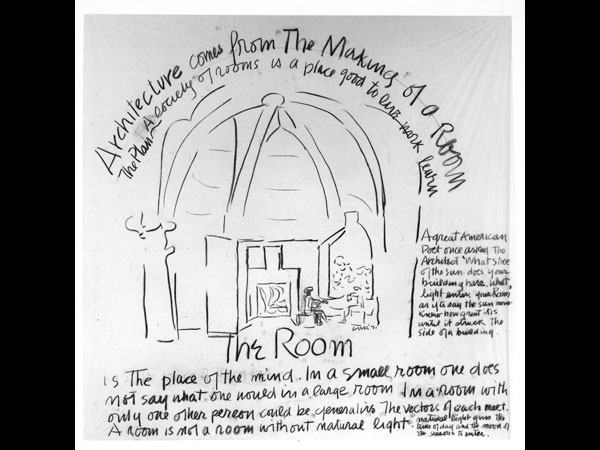

CREDIT: Architecture Comes From the Making of a Room, 1971. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of the artist.

CREDIT: Architecture Comes From the Making of a Room, 1971. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of the artist."Louis I. Kahn: The Making of a Room," a small exhibition at the Arthur Ross Gallery of the University of Pennsylvania, is a reminder that the famous architect still has much to teach us. This show, which concentrates on his drawings of interiors, begins with a sketch of an imaginary room, made for a 1971 Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition. Timeless is a hackneyed word, but how else to describe this little domed chamber: a fireplace, a window, two people talking. "In a small room one does not say what one would in a large room," Kahn writes. A characteristically gnomic utterance, but the humanist message of the drawing is crystal clear. This has something to do with the rough way in which it is made; in an age when architects are consumed—some might say overwhelmed—by whiz-bang digital wizardry, this scratchy charcoal sketch is a throwback to an earlier era.

-

Radbill Oil Company, Philadelphia, Stonorov and Kahn, 1944-47, renovation of offices. CREDIT: Elevation of Boardroom Including Table and Chairs. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Radbill Oil Company, Philadelphia, Stonorov and Kahn, 1944-47, renovation of offices. CREDIT: Elevation of Boardroom Including Table and Chairs. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.Louis I. Kahn was born in 1901, but his career was stalled by the Great Depression and World War II, and he didn't really get started until the 1950s. The oldest of the postwar generation of prominent American architects, he was unique in having had a Beaux-Arts education. This classical training would influence his later work, but in this rather stiff colored-pencil drawing of a Philadelphia boardroom we see him determined to be up-to-date, with a Picasso-like collage and a starkly functionalistic pinup wall made out of what appear to be oversize acoustic tiles. The chairs, also by Kahn, are a version of a Florence Knoll design of the same period. It's all very conventionally modern—no hint of what is to come.

-

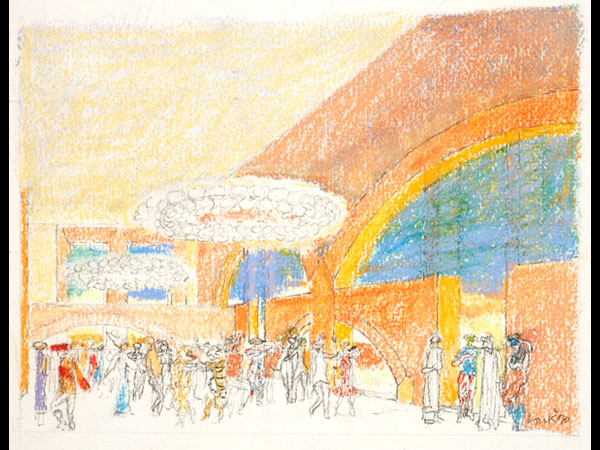

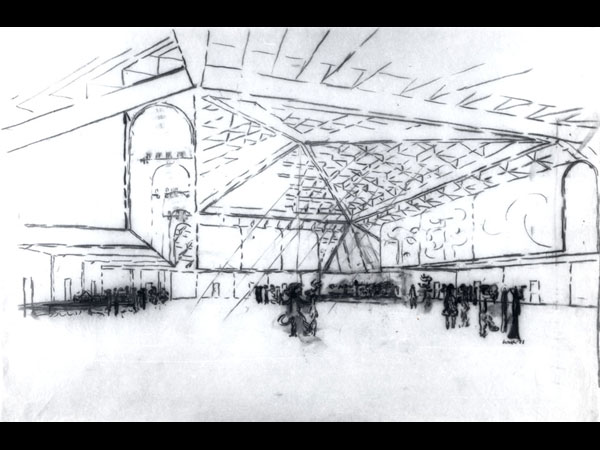

Performing Arts Center, Fort Wayne, Ind., 1959-73. CREDIT: Perspective of Upper Foyer. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Performing Arts Center, Fort Wayne, Ind., 1959-73. CREDIT: Perspective of Upper Foyer. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.By the late 1950s, Kahn had found his own voice. This pencil and pastel drawing portrays the upper lobby of a performing arts center in Fort Wayne, Ind. Despite the monumental Roman arches, this is a modern room, with stark brick walls and an exposed concrete ceiling. But what modern architect would show his building full of revelers at a costume party, dressed as harlequins and prancing lions and tigers? Kahn's approach to architecture is often portrayed as ethereal and spiritual; neither quality is apparent in this exuberant scene, which is a depiction, presumably for the client, of what the final building will be like, people and all.

-

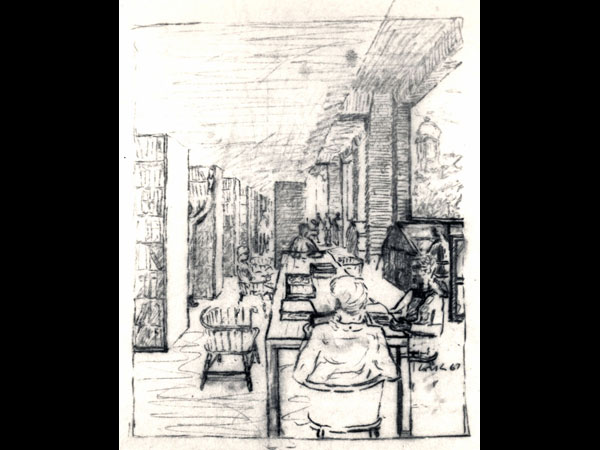

Phillips Exeter Academy, Library, Exeter, N.H, 1965-72. CREDIT: Perspective of Reading Area With Study Carrels. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical Museums Commission.

Phillips Exeter Academy, Library, Exeter, N.H, 1965-72. CREDIT: Perspective of Reading Area With Study Carrels. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical Museums Commission.The library at Phillips Exeter Academy is one of Kahn's most compelling buildings. This pencil drawing explains his simple concept: small reading carrels ringing the exterior perimeter of the building, and within, barely visible, the stacks where books are stored away from the light. What's interesting is that Kahn's drawing doesn't look anything like a conventional architectural rendering; it's more like a sketch of an actual place. Architects often include one or two human figures in their drawings to suggest scale, but here the students dominate the space, their obvious concentration conveying an atmosphere of quiet study in which the architecture figures as an almost incidental backdrop.

-

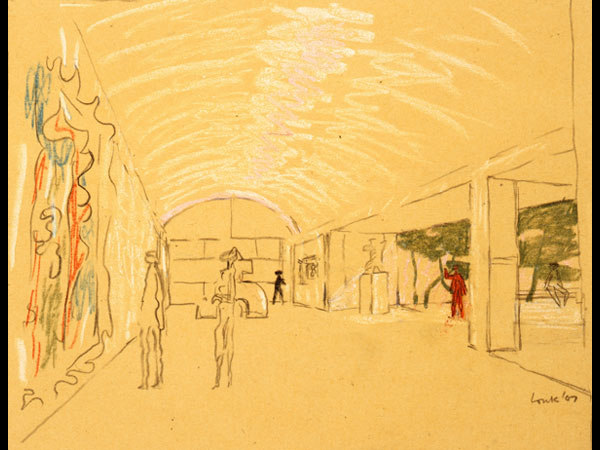

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966-72. CREDIT: First in a Series of Three Perspectives of a Gallery Showing Variations in Lighting and Seasonal Conditions. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania by anonymous gift.

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966-72. CREDIT: First in a Series of Three Perspectives of a Gallery Showing Variations in Lighting and Seasonal Conditions. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania by anonymous gift.According to Kahn biographer Carter Wiseman, "If silence was a key element of the Exeter library, light was the essence of his design for the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas." As with the Yale Center for British Art, the exterior of the Kimbell is rather plain; the architecture is all about the galleries and the way that they are lit. What Kahn called "white light" comes from skylights (not shown) and washes the vaulted ceilings, while "green light" filters in through a planted courtyard. He made three of these pencil and pastel studies to show the room in summer (right), winter, and at night. But it is the pair of art lovers in front of the painting who dominate this evocative drawing.

-

Inner Harbor Project, Baltimore, 1968-73, unbuilt. CREDIT: Perspective of Atrium. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Inner Harbor Project, Baltimore, 1968-73, unbuilt. CREDIT: Perspective of Atrium. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.Although Louis Kahn was a man of the city who lived and worked almost his entire life in Philadelphia, most of his commissions were built on college campuses and in the suburbs. He did design several downtown buildings, notably a congress hall for Venice, Italy, and an office tower for Kansas City, Mo., but neither was built. Nor was a large commercial complex on Baltimore's Inner Harbor, which consisted of several office and apartment towers, a hotel, and shops. The centerpiece of the project was a large gathering space, the so-called Banquet Hall (right). This charcoal sketch, intentionally vague, shows light streaming in through a complicated stepped-pyramid roof. It's unclear what's going on below. Have the Fort Wayne partygoers dropped in for a visit?

-

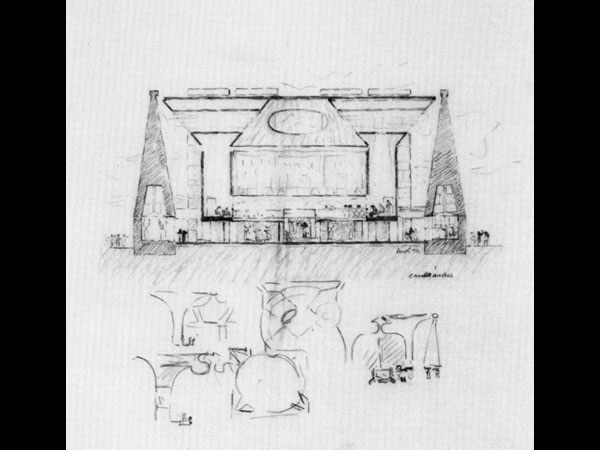

Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem, 1967-74, unbuilt. CREDIT: Section Studies. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem, 1967-74, unbuilt. CREDIT: Section Studies. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.Perhaps the most challenging room for an architect to design is a place of worship. In 1967, Kahn was commissioned to rebuild Hurva Synagogue, Jerusalem's main Ashkenazi synagogue, which had been destroyed during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. "A room is not a room without natural light," he taught. The inner sanctuary of this unbuilt design is roofed by four concrete umbrellas, with light entering through narrow slits between them. The sanctuary is surrounded by extremely thick stone walls containing niches, lit by candlelight, for individual reflection. Kahn often used an artist's Negro pencil, a greasier version of a carbon pencil, which gave his drawings a smudgy quality. This intentional tentativeness—impossible to achieve with a computer-generated graphic—shows the advantage of sketching, as the architect slowly works toward a conclusive solution.

-

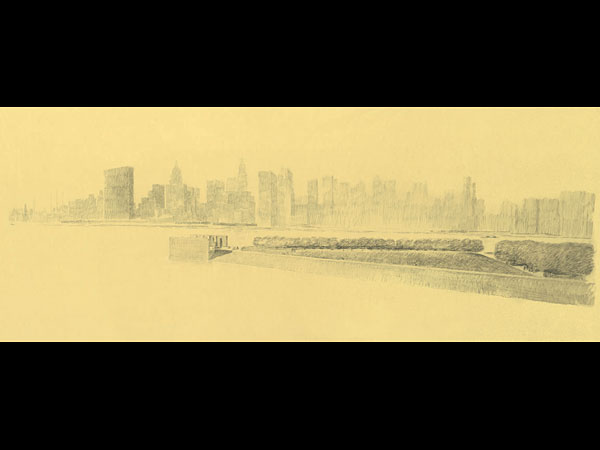

Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Roosevelt Island, N.Y., 1973-74, unbuilt. CREDIT: Bird's-Eye Perspective. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical Museums Commission.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Roosevelt Island, N.Y., 1973-74, unbuilt. CREDIT: Bird's-Eye Perspective. Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical Museums Commission.One of Kahn's last designs was the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial on the southern tip of Roosevelt Island in New York City. This large rendering, delicately drawn in colored pencil on yellow tracing paper, shows the entry courts defined by double rows of linden trees, and a blocky, granite-walled outdoor room containing a statue of the president. A hazy Manhattan skyline is in the distance. Kahn's rough sketches were working documents; this refined drawing was made to be shown to the client, and it demonstrates his skill as a draftsman. Although the memorial was not built, in part due to Kahn's death in 1974, there is now a possibility that the memorial will be realized in some form.

-

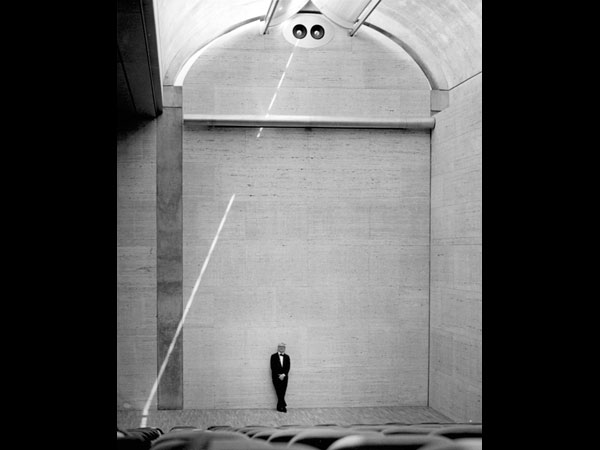

Louis Kahn in the auditorium of the Kimbell Art Museum, Aug. 3, 1972. Photograph © Robert Wharton, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Louis Kahn in the auditorium of the Kimbell Art Museum, Aug. 3, 1972. Photograph © Robert Wharton, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.A 1991* traveling retrospective exhibition of Kahn's work, "In the Realm of Architecture" cemented his position as the leading 20th-century American architect since Frank Lloyd Wright. At the time, Kahn was already becoming a somewhat distant figure. Since his death, only 17 years earlier, architecture had moved on—to Postmodernism, Deconstructivism, and even more arcane pursuits. His carefully crafted brick and concrete structures seemed old-fashioned, his concern for silence and light almost quaint, his smudgy pencil sketches a throwback to an earlier time. What a difference a few years make. Today, the last decade is starting to look uncomfortably like a neo-Gilded Age, with all the extravagance—including extravagant buildings—that implies. After this rich banquet, Kahn's brand of severe Modernism, with its self-effacing modesty and affecting, almost archaic simplicity, is a bracing tonic: a lean architecture for lean times. Charcoal, anyone?

Correction, Feb. 25, 2009: The article originally stated that the exhibition had been in 2001. (Return to the corrected sentence.)