The Architecture of Edward Hopper

-

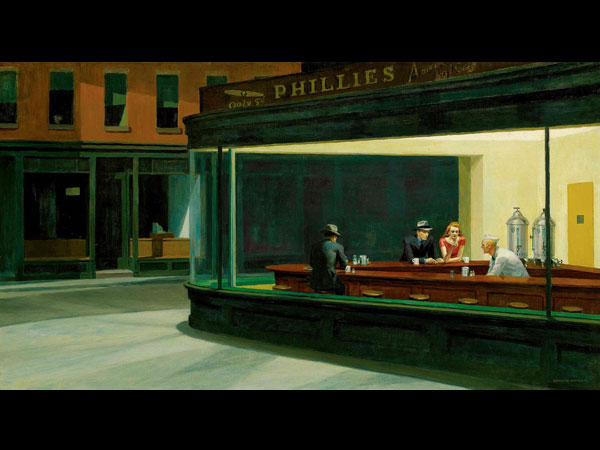

Edward Hopper, CREDIT: Nighthawks, 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of American Art Collection. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper, CREDIT: Nighthawks, 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of American Art Collection. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.The Edward Hopper retrospective that was on view in Boston and Washington, D.C., last year and is currently at the Art Institute of Chicago (until May 10) offers a splendid opportunity to experience the artist's masterful technique—in oils, watercolors, and etchings—and his dreamlike scenes of modern life. Nighthawks is his best-known work. This painting, which has been likened to van Gogh's Night Cafe and de Chirico's deserted urban streetscapes, is a reminder of the importance of architecture for Hopper and how much he—a Modernist with a taste for the old as well as the new—has to say on the subject. Here he contrasts the sleek Moderne diner, whose vast plate-glass window appears almost Miesian in its bleak transparency, with the 19th-century brick row houses in the background.

-

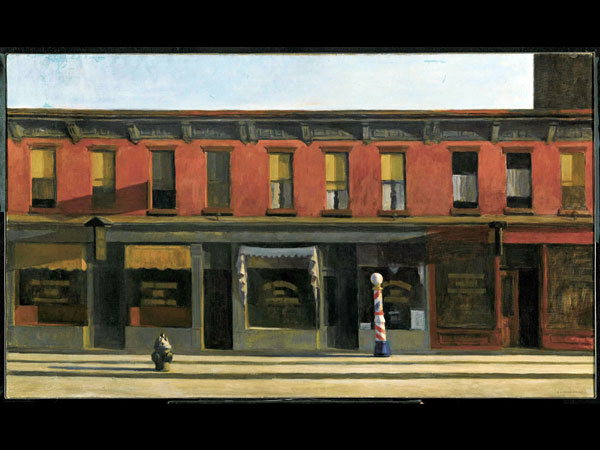

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Whitney Museum of American Art, N.Y. Purchased with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Whitney Museum of American Art, N.Y. Purchased with funds from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.Edward Hopper (1882-1967) lived and worked his whole life in New York. There was nothing sentimental about the way he depicted the city—he painted hotel lobbies and offices, movie houses and cafeterias, and railroad-station platforms. But never skyscrapers, despite the fact that this was the era of the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building, and Rockefeller Center. Of course, skyscrapers were glamorous, and Hopper had no interest in glamour or in conventional beauty. His home and studio for more than 50 years were the top floor of 3 Washington Square North, and Early Sunday Morning portrays a monotonous row of ordinary houses on nearby Seventh Avenue. It is a generic urban scene—businesses below, rented rooms above. The slightly varied storefronts act as a foil to the regular row of windows, whose staggered blinds and varied curtains are all that attest to human occupancy. "This is how we build our cities," Hopper seems to say without passing judgment.

-

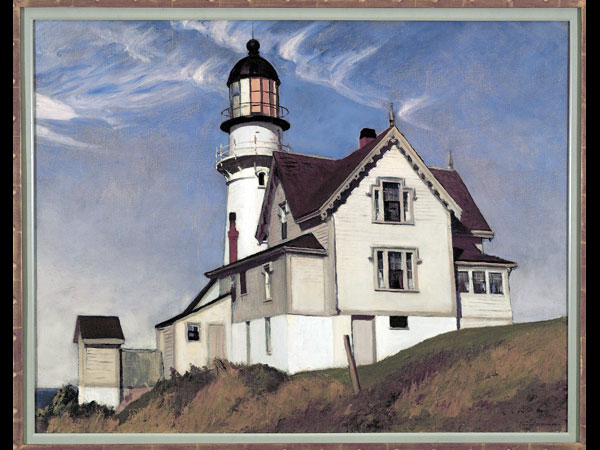

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Captain Upton's House, 1927. Collection of Steve Martin. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Captain Upton's House, 1927. Collection of Steve Martin. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.For an artist associated with depicting urban angst, Hopper painted a lot of rural architecture. Between 1914 and 1929, he and his wife, Jo, summered in Maine, where he sketched local buildings, including lighthouses. The hardy staple of wall calendars and jigsaw puzzles was an odd choice of subject, but he painted so many lighthouses that they are as much a Hopper motif as his scenes of urban alienation. Captain Upton's House was painted in 1927. Only three years earlier, Le Corbusier had published Toward an Architecture, in which he proclaimed that "the house is a machine for living in," and lighthouse towers were the sort of utilitarian structure that Modern architects admired. But Hopper sends a different message. His house is no machine—far from it. Its dainty ornament contrasts strongly with the sturdy tower: humanist architecture vs. functional engineering.

-

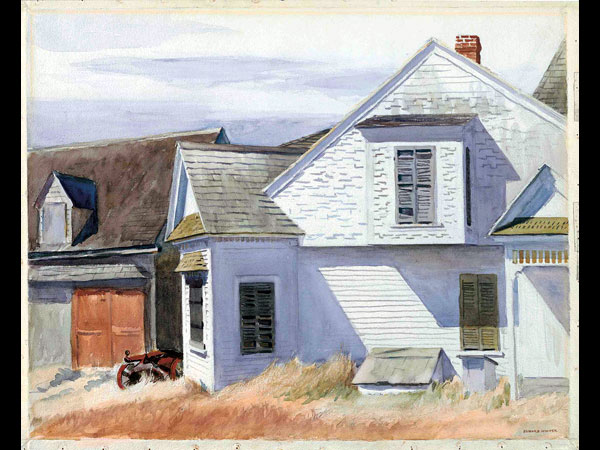

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Marshall's House, 1932. Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn. Purchased through the Gift of Henry and Walter Keney. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Beginning in 1930, the Hoppers spent their summers in South Truro, Mass., a small town on the tip of Cape Cod. Hopper painted more lighthouses, as well as boats, but he was drawn mostly to houses. Equally as unsentimental as his urban scenes, the rural houses are depicted as volumetric compositions in the manner of Cézanne, but they are never abstractions. Marshall's House is typical: A modest dwelling with a red tar-paper roof and a screened porch pushed awkwardly into the corner, it is slightly the worse for wear, the window shutters no longer tightly closed, the screens a little loose, the gutter downspout at the corner bent and out of plumb. "How threadbare plain the 'real,' the beloved America has always been in fact," Vincent Scully once wrote in another context, "but how, like these houses stretching upward, it yearns." Yearnful is a good way to describe this little house, with its modest architectural pretensions.

-

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: House on Pamet River, 1934. Whitney Museum of American Art, N.Y. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: House on Pamet River, 1934. Whitney Museum of American Art, N.Y. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.This house in Truro is almost picturesque, thanks to its haphazard Victorian additions. Jo described it as an "amazing old place—with every sort of excrescent hung on to it—without rhyme or reason … going in and out of planes, shapes, angles, textures." Hopper's curiously cropped watercolor is a forerunner (40 years before the fact) of the "complexity and contradiction" of some of the small houses that Robert Venturi designed in New England in the 1970s. Not that Hopper was an early Postmodernist; he shared Venturi's interest in odd juxtapositions as well as in ordinariness.

-

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Kelly Jenness House, 1932. Mr. Richard M. Thune. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Hopper's urban buildings are rooted in place, but his country houses, despite their ageless setting, often appear provisional. This ordinary Cape Cod cottage, for example, looks as if it had dropped into the dunes out of the sky. Like many American wood-frame houses, it is sitting on the ground rather than rising from it. This lightness produces an endearingly fragile appearance, as if a big wind, or any powerful force of nature, could blow it away.

-

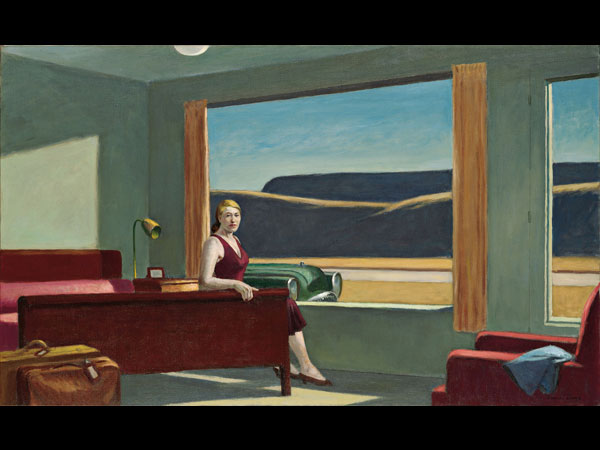

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Western Motel, 1957. Yale University Art Gallery. Bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Western Motel, 1957. Yale University Art Gallery. Bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.Landscape also figures in this later work, painted while Hopper and Jo were on a winter sojourn in California. (She models for him here, as she did in many of his oil paintings.) Some artists would have focused on the moody landscape, but Hopper frames the view through the picture window of a motel room. The room looks brand-new, although there is nothing particularly stylish about the stark decor. The vista of distant hills is beautiful, but, like much modern architecture, the motel feels isolated from the surrounding landscape. Inside and outside are two different worlds; Hopper offers us no middle ground except for a strip of highway.

-

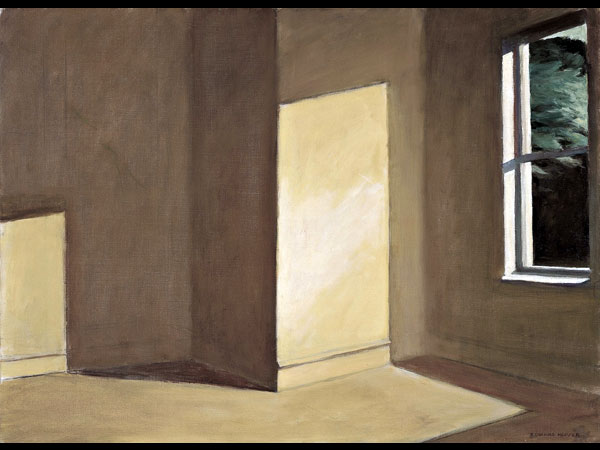

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Sun in an Empty Room, 1963. Private Collection. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.

Edward Hopper,CREDIT: Sun in an Empty Room, 1963. Private Collection. Image courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago.Space and light are the twin hallmarks of Modern architecture. Space and light were always a part of the experience of buildings, but by eliminating ornament and modulated surfaces, Modern architects brought them to the fore. This is what Hopper captures in this luminous painting, one of his last, painted when he was 81. This particular room, which belonged to the painter, is empty—or recently vacated—yet it does not feel abandoned. Was it Hopper's bedroom? When asked what he was after in the painting, he answered, "I'm after ME."

-

Portrait of Edward Hopper, Aug. 14, 1960, in Truro, Mass., by Arnold Newman/Getty Images.

Arnold Newman photographed an elderly Hopper sitting regally in front of the summer house that he and Jo had built in Truro 30 years earlier. (Jo flits, waiflike, in the distance.) The sturdy shingled structure, which combined a studio with a north window at one end and living accommodations at the other, was designed by Hopper, who was an accomplished carpenter. What kind of architect was the painter? Surprisingly, a classicist. The gable-roofed box lacks any appurtenances—no lean-tos or porches—and it sits four-square in the sandy hills, as solid as an ancient Greek temple. The style is traditional New England Colonial, stripped to its bare essentials, but the Modern sensibility is entirely Edward Hopper's.