A Gray Lady

-

Witold Rybczynski.

Witold Rybczynski.The New York Times used to be nicknamed the Gray Lady for its stolid reporting style and its reliance on text rather than pictures, although, with the advent of color printing—and the addition of breezy lifestyle sections—the sobriquet no longer fits. Nevertheless, the newspaper's new Eighth Avenue home is not only gray but also—if I may risk an accusation of sexism—ladylike. Lacy screens shroud the cruciform tower like a Victorian dowager's veil and extend beyond the 52nd floor to form a delicate tiara. From a distance, the overall impression is distinctly subdued, almost dull, and it makes you wonder what the architect, Renzo Piano, is up to.

-

Witold Rybczynski.

Witold Rybczynski.The distant impression of delicacy changes at street level. From the glass canopy suspended over the sidewalk, to the exposed columns, beams, and diagonal braces, the building flexes its muscles in plain view. Structure hasn't been celebrated this boldly in Manhattan since the George Washington Bridge.

-

Witold Rybczynski.

Witold Rybczynski.Thirty years ago, Piano and Richard Rogers designed the Pompidou Center, which heralded high-tech architecture and culminated a decade later in Norman Foster's Hongkong & Shanghai Bank. Since then, Foster has moved away from high tech, as evidenced in his sleek Hearst Building, just up Eighth Avenue from the Times. So has Piano, whose addition to the Morgan Library in New York typifies his current low-key approach. However, in the New York Times Building (designed in association with FXFowle) Piano returns to his Pompidou roots; not exposed pipes and ducts—those were always impractical—but dramatic structural details that say, "This is how I am made."

-

Witold Rybczynski.

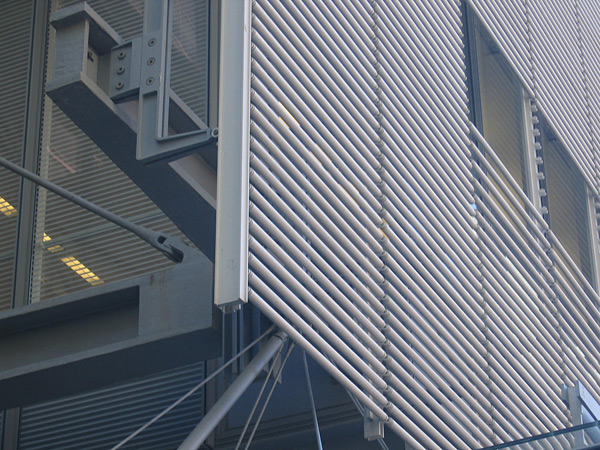

Witold Rybczynski.The Renzo Piano Building Workshop is currently designing extensions to museums in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The firm has been so successful at winning commissions that it is frequently described as a "safe" architectural choice. But Piano has often taken risks—think of the all-glass roofs of the Menil Collection in Houston and the stunning Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas, or the glass louvers and wooden screens that shroud the New Caledonia cultural center. The New York Times Building also has unusual screens although, to my eye, the effect of the second skin of ceramic rods (right) is more prosaic than magical. The rods, which serve to shade the all-glass facades, reminded me of fluorescent tubes; from the interior the effect is of an oversized security grate.

-

Witold Rybczynski.

Witold Rybczynski.Piano won the New York Times Building commission in an invited competition, beating out Cesar Pelli and Norman Foster. (Frank Gehry and David Childs of SOM withdrew before the final judging.) One reason that clients choose Piano, I think, is that they believe he will pay as much attention to the interior function of a building as to its exterior appearance. That is the case here. The street level will be enlivened by shops, a restaurant, and a performance space. Thanks to ultraclear glass, the lobby is exceedingly transparent, producing the impression of an indoor piazza, if a piazza had white oak floors. The use of a wooden floor in an office building is unusual—and a classic Piano detail. Wood is pleasant to walk on, attractive to look at, and it subtly humanizes the space without a lot of fanfare. When you see it, you think "Of course. Why haven't we done this before?"

-

Witold Rybczynski.

Witold Rybczynski.The New York Times Building is not a corporate trophy or a crowd-pleasing cultural attraction, but a commercial real-estate venture (the newspaper occupies the podium and the first 28 floors; the rest of the tower is leased). The owners deserve credit for their architectural ambition, but, as often happens in commercial projects, financial considerations have compromised design. The base of the building, originally a dramatic stepped-back podium with a five-story atrium, has been greatly simplified. Instead of an enclosed atrium, there is now an open-air inner court. The birch and moss garden, designed by Hank White and Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, is exquisite, although it appears more decorative than usable, like a large terrarium.

-

Nic Lehoux.

Nic Lehoux.Newsrooms are the heart of a newspaper. Rather than being hidden away, as they were in the old Times building on 43rd Street, here the newsrooms are in a low annex visible from the street, especially at night. The entire news operation is housed on three vast 65,000-square-foot floors overlooking the landscaped court and giving reporters a view of birch treetops—in midtown Manhattan! The top two floors surround a two-story central atrium (right), whose skylight creates the atmosphere of a large atelier, rather than an anonymous office.

-

Nic Lehoux.

Nic Lehoux.Recently the American Institute of Architects announced that Piano will receive its 2008 gold medal. The press release mentioned his "humane environments," which means, I suppose, that he thinks about the occupants of the buildings he designs. The employees' cafeteria of the New York Times Building occupies a two-story space on the 14th floor, stretching across the entire east end of the building. Many architects would have used its design as an excuse for a star turn—as Frank Gehry did in the cafeteria of the Condé Nast building. Piano's approach is simpler: provide a generously proportioned, airy space with views of the city, fill it with round tables and comfortable chairs, and let people relax, talk, and eat their lunch.

-

Nic Lehoux.

Nic Lehoux.The newspaper office interiors, designed by Gensler, include an unusual feature: They are interconnected by open stairs at the periphery (right), which encourages easy communication between floors—no more running up and down dismal fire stairs. Eleven-foot ceilings are a less obvious innovation. So is the lighting system, which automatically adjusts to complement the varying levels of natural light in different parts of the room. Another energy-conserving feature: conditioned air is distributed through the floor. Since air does not have to travel as far as if it were blown down from the ceiling (as in most office buildings), it can be less cold—and under less pressure—which not only saves energy but is also more comfortable.

-

David Sundberg/Esto.

David Sundberg/Esto.When the original competition for the New York Times Building was announced, an executive of the newspaper was quoted as saying, "We want a building that is an icon." Piano and his collaborators have given the Times—and its 10,000 employees—something more valuable: a really good workplace. The New York Times Building isn't perfect, but you have to go back to the 1950s and the glory days of SOM and Gordon Bunshaft to find a commercial office building designed with a similarly strong sense of conviction. More recent Manhattan towers have demonstrated chiefly nervous novelty: sliced-off Citicorp, chopped-corner IBM, quasi-classical 60 Wall Street, enlarged Chippendale AT&T, and pyramid-topped World Financial Center. American architects who, after all, invented the skyscraper, appeared lost. Who would have thought that it would be Europeans—Piano, Foster, and soon Rogers at Ground Zero—who would be the ones to show the way?