A History of the Hotel

-

Michael Kamber/CREDIT: New York Times/Redux.

Michael Kamber/CREDIT: New York Times/Redux.Hotels can be found almost everywhere in the world today. There is an ecotourist hotel built into the forest canopy of the Amazon rain forest and a high-altitude hotel facing Mount Everest that can be reached only on foot or by yak. The Times reported recently that one reason Turkey would like to avoid war with Iraqi Kurds is the $25 million, 187-room luxury hotel (right) being built in Dohuk by a Turkish construction company. The hospitality industry is one of the fastest-growing segments of the international economy. So it is easy to forget that the hotel, as we know it today, was once a new invention, an experiment that initially met with failure and endured periods of slow, halting development.

-

John Lewis KrimmelCREDIT: , Village Tavern, 1813-14. Toledo Museum of Art, Florence Scott Libbey bequest in memory of Maurice A. Scott.

John Lewis KrimmelCREDIT: , Village Tavern, 1813-14. Toledo Museum of Art, Florence Scott Libbey bequest in memory of Maurice A. Scott.The history of the modern hotel begins in America. For the first two centuries of European settlement, the colonists made do with travel accommodations that were even more rudimentary than most in the Old World. American inns and taverns were kept in small, unimpressive buildings, mostly dwelling houses that were indistinguishable from homes but for the signs hanging outside. Inside, patrons squeezed into bars that were little more than living rooms with built-in wooden cages where the liquor was kept—like the one depicted in this painting by John Lewis Krimmel. Overnight guests had to put up with a more intimate form of crowding—they were expected to share not just their rooms, but their beds as well. This practice persisted for many years: hence the scene in Moby-Dick in which Ishmael must share his bed at the Spouter-Inn with the tattooed harpooneer Queequeg.

-

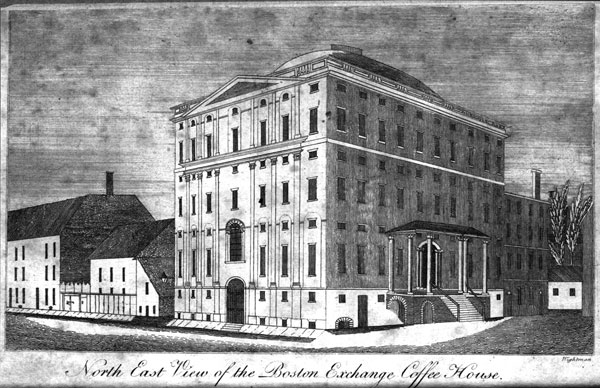

The Boston Exchange Coffee House and Hotel, Frontispiece from CREDIT: Omnium Gatherum, 1809. University of Chicago Library.

The Boston Exchange Coffee House and Hotel, Frontispiece from CREDIT: Omnium Gatherum, 1809. University of Chicago Library.The first hotels were built in the 1790s. They were the creations of wealthy urban merchants who sought to move the still-agrarian United States toward a commercial future by improving the nation's travel infrastructure (and in the meantime, they hoped to profit personally by driving up the value of their nearby real-estate holdings). These hotels featured ambitious architecture and offered private bedchambers and luxurious public rooms. The Union Public Hotel, which broke ground in Washington in 1793, was an 11-bay structure in the stately Georgian style, rose to a height of 70 feet, and contained dozens of rooms. New York's City Hotel, which opened four years later, adopted the then-modish Federal building style, stood taller than all but the spires of the city's largest churches, and boasted 137 rooms. These early hotels were intended as dramatic architectural statements—this one, the Boston Exchange Coffee House and Hotel, was said to be the largest privately owned building in the United States.

-

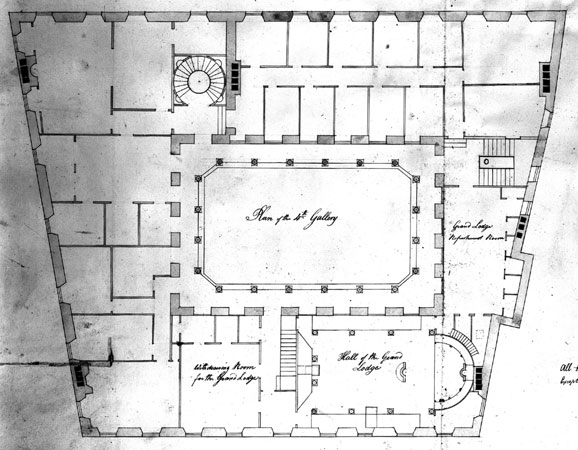

Plans of Boston Exchange Coffee House, Fourth Gallery. Courtesy of the Bostonian Society/Old State House Museum.

Plans of Boston Exchange Coffee House, Fourth Gallery. Courtesy of the Bostonian Society/Old State House Museum.But in other respects, these early hotels were tentative and disorganized. The fourth-floor plan of the Boston Exchange displays a jumble of spaces, with small bedchambers mixed in alongside larger unmarked rooms as well as a "Hall," a "Refreshment Room," and a "Withdrawing Room" belonging to the "Grand Lodge" of Freemasons. The architectural evidence suggests that the hotel's builders were unsure whether guest-room rentals alone would be profitable; they therefore leased or sold upstairs spaces to long-term tenants in order to diversify and stabilize their sources of income. They were right to be worried. These first-generation hotels had been built on speculation and were too grand for the relatively small number of travelers at the time. As a result, nearly every single one went bankrupt, ruining investors and in at least one case landing the proprietor in debtor's prison. So while the earliest hotels represented a bold and even visionary attempt to create a radically new building type, from a financial standpoint they were a failure.

-

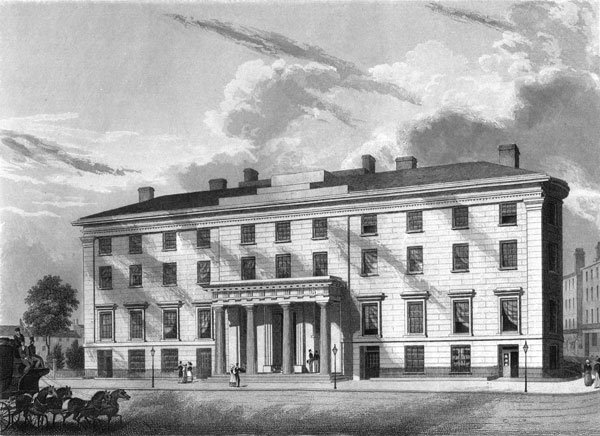

The Tremont House Hotel, Boston. Collection of the author.

The Tremont House Hotel, Boston. Collection of the author.It wasn't until the mid-1820s that Americans summoned the courage to undertake another round of hotel construction. This time, the impetus came from competition among Eastern cities to control regional economies. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 allowed New York City to dominate a vast western hinterland. But other cities fought back with infrastructural projects of their own: They sponsored canals, chartered private railroad companies, and underwrote a new generation of hotels. City leaders organized legislative support and promoted stock sales, using both public prestige and private fortunes to finance grand new ventures like Baltimore's City Hotel (1826), Washington's National Hotel (1827), Philadelphia's United States Hotel (1828), and Boston's Tremont House (1829, right). This enthusiasm for hotel building would persist with only a few interruptions for the next century.

-

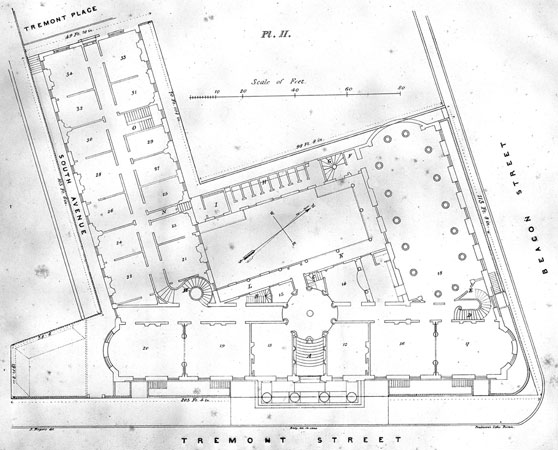

Plans of the Tremont House. Courtesy of the Bostonian Society/Old State House Museum.

Plans of the Tremont House. Courtesy of the Bostonian Society/Old State House Museum.Many of the basic architectural features of modern hotels were worked out in these years. This plan of the Tremont House displays the hotel's grand entryway, its lobby and front desk, and the public rooms, offices, and commercial spaces that filled its main floor. It also reveals the architect's decision to place the bedchambers in a special wing separated from the hotel's public areas. Climbing the spiral stairway labeled M, guests would leave behind the noise and hubbub of the lobby and seek out their rooms along lengthy corridors lined with numbered doors—an experience not so different from a present-day hotel stay. Indeed, searching Google Images with the words hotel floor plan yields scores of recent hotel building layouts quite similar to this nearly 180-year-old example.

-

The United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.CREDIT: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 2, 1876. Collection of the author.

The United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.CREDIT: Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 2, 1876. Collection of the author.These 19th -century hotels were recognizably modern not just because of their physical structure but also their social character. American hotels were famously gregarious places. Because hotelkeepers still couldn't turn a profit on room charges alone, they needed to attract local people into their premises and sell them food and especially drinks. Hoteliers offered comfortable and elegant interiors, and townspeople happily congregated in hotel parlors, dining halls, barrooms, and lobbies, like this one at the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Foreign travelers frequently commented on the easy familiarity of hotel crowds: One visitor noted "the constant amalgamation of the different classes in hotels," and another remarked that "at the hotels … you have frequent opportunities of seeing all classes: from the best and highest … to the needy speculator."

-

Dining room, Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York City,CREDIT: Harper's Weekly, Oct. 1, 1859. Collection of the author.

Dining room, Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York City,CREDIT: Harper's Weekly, Oct. 1, 1859. Collection of the author.The democratic sociability of American hotels was distinctive, and very much at odds with travel accommodations across the Atlantic. European hostelries were typically designed to keep their guests separated in their own suites of rooms, a custom originally devised to allow noblemen to keep aloof from the hoi polloi. When they visited the United States, Europeans reacted indignantly to the social promiscuity of hotels, often citing crowded dining halls like this one at New York City's Fifth Avenue Hotel. A 19th-century visitor from France groused that many American hotels "offer hardly more privacy than bee-hives."

-

Victoria Hotel, Unter den Linden, Berlin, Germany, 1905. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Victoria Hotel, Unter den Linden, Berlin, Germany, 1905. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.Yet even as they disdained the public culture of American hotels, Europeans emulated them. Published accounts of hotels in Europe often referred to those in the United States. For example, in the 1850s, British newspapers made note of one London hotel's "American bar" and described its "hair-cutting saloon" as "another American luxury," and noted that another had been built "on the admirable scale of [hotels] of the American cities." By the second half of the 19th century, European observers acknowledged Americans as both the originators of the modern hotel and the trendsetters in hotel-keeping. "The American hotel," remarked a London journalist in 1861, "is to an English hotel what an elephant is to a periwinkle." And in 1875, another trans-Atlantic visitor concluded: "In the United States, the hotel is literally an 'institution.' The system, initiated here some forty years ago, has revolutionised the hotel system throughout the world."

-

Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, Detroit Publishing Company, postcard No. 70423, c. 1912. Collection of the author.

Blackstone Hotel, Chicago, Detroit Publishing Company, postcard No. 70423, c. 1912. Collection of the author.The American hotel system was revolutionary because it offered hospitality that was indeed institutional. Hotel-keepers were more interested in serving a relatively broad clientele than in currying favor with prominent patrons. The contrast with Europe was ably expressed by an English writer who warned in 1860 that visitors to the United States "must not look for the obsequious attentions which greet a new arrival at an English hotel." In America, he explained, "particular attention to individuals is … out of the question where guests are booked by the score and dined by the hundred." But while America's hotel system was the most extensive one in the world by that time, there were limits to who was welcome. Most citizens could not afford to stay in a first-rate hotel, black people were rigidly excluded from white-owned hotels, and many resort hotels refused to accommodate Jews.

-

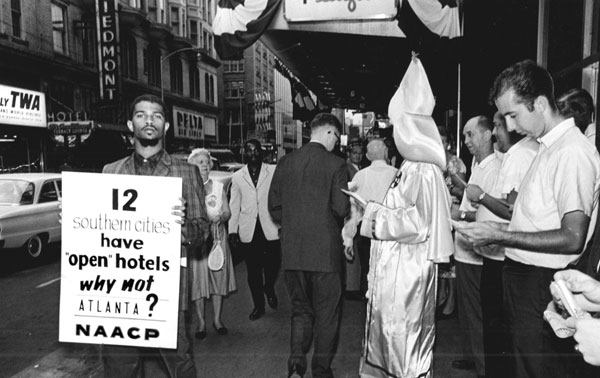

Photograph of demonstration against segregated hotels, CREDIT: Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 4, 1962. Bill Young/Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Photograph of demonstration against segregated hotels, CREDIT: Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 4, 1962. Bill Young/Atlanta Journal-Constitution.It was only in the 20th century that American hospitality became truly democratic. Beginning in 1908, E.M. Statler challenged the hotel industry's attention to the wealthy by declaring that he would offer hospitality "at a price ordinary people can afford." Statler's slogan, "A bed and a bath for a dollar and a half," launched his hotel empire and made him, as a 1950 trade journal put it, "The Hotel Man of the Half Century." A decade later, the civil rights movement launched a wave of demonstrations against discrimination in travel facilities. Martin Luther King's 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech—which evoked the plight of black wayfarers with the reminder that "our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities"—helped persuade Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations.

-

Hôtel de Glace Québec-Canada copyright © CREDIT: www.xdphoto.com.

Hôtel de Glace Québec-Canada copyright © CREDIT: www.xdphoto.com.Today, the world of hotels continues to expand and diversify. The hotels that garner the most publicity are typically those with offbeat or opulent accommodations, such as the hotels in Canada and Sweden that are made entirely of ice or the Miami hotel so impossibly lavish that some say it's worthy of a six-star rating. But the most significant new hotels may be the ones opening their doors in developing regions like western China and even Iraqi Kurdistan. These places may yet be a long way from embracing American-style democracy, but whether they know it or not, they've already embraced one of America's signature institutions.