The Spire of Dublin

-

Photograph licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5. Courtesy wikipedia.org.

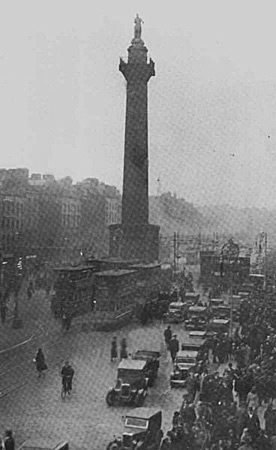

Photograph licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5. Courtesy wikipedia.org.Watching the World Trade Center Memorial stumbling to completion, one might be excused in thinking that building a modern memorial is inevitably destined to be a star-crossed enterprise. Remember the controversy that surrounded the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C.? That's one reason why the Spire of Dublin, which was inaugurated in July 2003, is impressive. Nelson's Pillar (right) was erected in central Dublin in 1809 to memorialize the British admiral and was demolished in 1966 after being fatally damaged by an IRA bomb. In 1998, the city held an international competition to find a replacement. The winner was Ian Ritchie Architects of London, which proposed a slender spike rising not 136 feet, like the original column, but an astonishing 400 feet.

-

Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects.

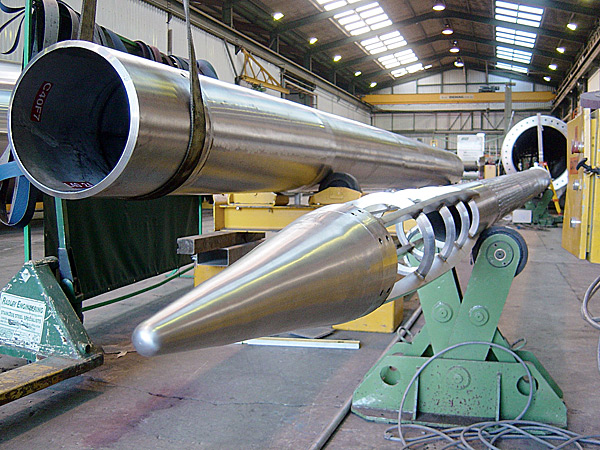

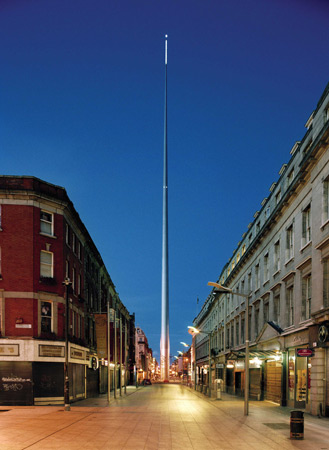

Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects.The new monument, which is located at an important intersection on Dublin's O'Connell Street, is not a commemorative memorial, but it serves as an urban landmark. In that sense it resembles the Eiffel Tower, which, although it has come to symbolize Paris, began merely as a feat of engineering. Like Eiffel, Ritchie based his design on structural logic, not sculptural effect. The spike tapers as it rises, from a diameter of 10 feet at the base to 6 inches at the apex. The eight long sections of hollow steel tubing were prefabricated in a factory. The topmost section (at right) contains aviation warning lights.

-

Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects.Although the project was not entirely without controversy—a court case by a disgruntled contestant held up construction for two years—the Spire was ready to be erected in December 2002. The pieces were individually hoisted into place and bolted together, except for the last section, which had a threaded connection (making it surely the largest bolt in the world). The construction process had to be completed swiftly, partly because of the downtown location and partly to minimize the time that the incomplete structure remained vulnerable to winds. A tower this tall requires internal mass dampers to counter swaying, and as the Spire was erected, the engineers (Arup) had to regularly recalibrate the dampers to take into account the changing shape.

-

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.Like many modern monuments, the Spire is not raised on a plinth. It rises out of a base that is flush with the level of the adjacent sidewalk. Since the shaft does not touch the base, the effect is slightly mysterious, as if the metallic spike had pushed its way up out of the center of the Earth. The circular base is inscribed with a spiral (a motif found in prehistoric Celtic megaliths), and when it rains, the grooves retain water and create the effect of a reflecting pool. The base is bronze, a traditional material for monuments, because of its longevity and the attractive patina it acquires as it ages.

-

Left: Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects. Right: Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Left: Ian Ritchie Architects © Ian Ritchie Architects. Right: Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.The Spire itself is made of austenitic stainless steel, an alloy with a high tensile strength. The lowest 33 feet of the surface are brightly polished and act as a mirror, reflecting people, traffic, and movement. In addition, a decorative pattern is incised into the surface in a process similar to sandblasting. The organic-looking shapes, based on the strata of the bedrock beneath the monument, counters the impression that this is merely a mechanical object.

-

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.Ritchie calls the Dublin Spire an "act of urbanism," that is, it's a landmark, an orientation point, a meeting place, and a vertical exclamation mark in a city that is still largely horizontal. In its precision and streamlined lift, it also evokes the "new" Ireland. Modern architects sometimes justify the most egregious impositions on historical urban environments by citing the "contrast" between old and new, but here the contrast actually seems to work.

-

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Barry Mason Photography © Ian Ritchie Architects.What does the Dublin Spire mean? Whatever you want. There is no writing, no iconography, no overt symbolism. This spire is not a sign. St. Augustine said of signs that if you didn't know what an object was a sign of, it could teach you nothing, but if you did know, what more could you learn from it? That's why the most potent monuments—the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem, the Kaaba at Mecca, the Washington Monument—lend themselves to many interpretations.

-

Ian Ritchie Architects Ltd/Igor Marko © Ian Ritchie Architects.

Ian Ritchie Architects Ltd/Igor Marko © Ian Ritchie Architects.In May 2007, Ian Ritchie Architects won another international competition, for a monument in Holyhead Harbour, Wales. The so-called Landmark Wales will consist of three pillars with different cross-sections: one circular, one square, and one cruciform. The pillars—the tallest is 263 feet high—are solid granite, post-tensioned within by steel cables. Like the Dublin Spire, the monument gains its power from its engineering, rather than from symbolism. Perhaps that's what's wrong with the design for the World Trade Center Memorial—it is relentlessly literal; the two tower footprints, the names of the victims, the inevitable visitor center. (It must be said that this is chiefly the fault of the committee that created the original program.) Wouldn't it have been better if the memorial had been more like Ritchie's soaring spires, uplifting and inspiring, but also mute?