Green Unseen

-

CREDIT: Ecol Operation. Photograph by Denis Plain. Originally published in "Déchets industriels devenues maison ecologique" by Gaby Perreault-Dorval. Perspectives, 31 December, 1972: 4.53.

CREDIT: Ecol Operation. Photograph by Denis Plain. Originally published in "Déchets industriels devenues maison ecologique" by Gaby Perreault-Dorval. Perspectives, 31 December, 1972: 4.53.Conserving energy and natural resources, and factoring carbon emissions and environmental impact into building design, are all good things. So are reusable building materials, although the benefits of reuse in a distant future can be hard to estimate. But does all this really amount to a new type of "green architecture," or "eco-tecture," as the New York Times Magazine inelegantly called it not long ago? Or is green design just the equivalent of better plumbing?

We've been here before. Thirty-five years ago, my colleagues and I at McGill University's Minimum Cost Housing Group in Montreal built a model house that demonstrated a number of energy-saving and environmentally friendly features. These included a self-contained toilet, a rooftop solar still to recycle shower water, a wind machine to generate electricity, and a solar oven (in foreground at right). We gratefully accepted Buckminster Fuller's suggestion and christened the house the Ecol Operation.

-

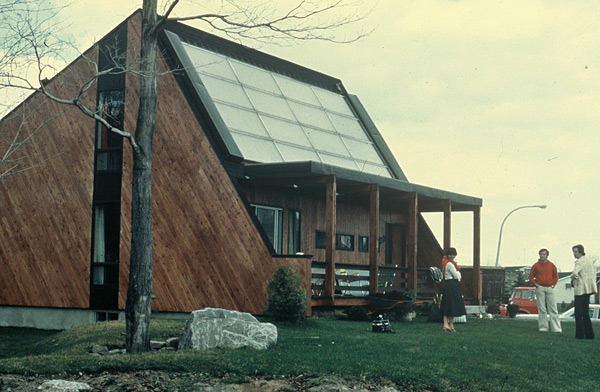

Photograph of a solar house in Quebec courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph of a solar house in Quebec courtesy Witold Rybczynski.In the early 1900s, visionary German architects idealized glasarkitectur, as if the material signaled a cultural revolution. New materials, and new technological concerns, often seem to turn architecture on its ear. After the energy crisis of 1973, there was a lot of interest in "solar houses," houses that used the sun's energy for heating. One way to capture solar heat is to circulate water under a glass-covered solar collector. This requires pumps, storage tanks, and a lot of pipes. The collector must face south, and since the winter sun tends to be low (at least in the Northeast), the collector must also be tilted at a steep angle. The problem with solar houses, like this example, was that they tended to resemble wedges of cheese. That's what happens when a single factor—how you heat a building—is given precedence over all the rest.

-

Kelbaugh House. Courtesy Doug Kelbaugh.

Kelbaugh House. Courtesy Doug Kelbaugh.In the late 1960s, a French scientist named Félix Trombe invented a solar heating system in which air warmed by the sun circulated by gravity. A south-facing thick concrete or masonry wall, behind a layer of glass, absorbed solar rays during the day and radiated heat into the interior at night. Since there were no pumps or fans, it was referred to as a "passive" system. The advantage of Trombe walls was that they were easier to integrate into buildings than tilted panels. Doug Kelbaugh built this passive solar house for his own family in Princeton, N.J., in 1975. An attached greenhouse is on the right. Note that the south-facing concrete wall has windows cut into it for light and view. It is a nice modern design, although the commercial-looking glass wall is not everyone's idea of a homey garden facade.

-

Photograph of Ferrero House, St. Marc, Quebec courtesy Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph of Ferrero House, St. Marc, Quebec courtesy Witold Rybczynski.A less radical approach than active or passive solar heating is "solar tempering." The rules are simple: Have as many windows as possible facing south and as few as possible facing north; provide some thermal mass (concrete floors or walls) inside the building to absorb heat during the day; and use as much insulation as you can afford. The result is a house that does not cost much more than a conventional home to build, consumes less energy, and, most important, can be designed to accommodate the many requirements of good domestic architecture. I built the example at right in rural Quebec in 1981. The large south-facing windows (which have insulated blinds for nighttime) allow the sun's heat to warm the house in the winter. The sunroom, whose roof is shaded in summer, can be used during sunny, cool weather. Since the best way to save energy is to consume as little as possible, the most effective energy-conserving technique is to make the house small: In this case, three bedrooms, a study nook, and a sauna are shoehorned into 1,200 square feet.

-

Lewis Center. Courtesy Oberlin College.

Lewis Center. Courtesy Oberlin College.Just like the wedge-shaped solar houses of the 1970s, there is an anticipation that green buildings should look different. Hence the popularity of grass roofs and bamboo plywood. Since the thermal efficiency of glazing has been greatly improved in the last two decades, green buildings tend to use lots of glass. The Lewis Center for Environmental Studies at Oberlin College in Ohio was designed by William McDonough, who specializes in energy conservation and is inevitably referred to as a green architect. Green buildings are described as "sustainable," although it is unclear exactly what this means. Most buildings will last a very long time, as long as bricks are repointed, woodwork is regularly repainted, and mechanical gizmos are upgraded as they become obsolete. Motorized windows, like the ones in this building, will eventually break down and have to be replaced. The Lewis Center claims to be a "net energy exporter," which is a good thing; at more than $344* per square foot to build, roughly twice the cost of a conventional academic building of similar size, the income will come in handy.

Correction, Aug. 9, 2007: The article originally claimed that the Lewis Center cost more than $500 per square to build.

-

Hotchkiss residence halls. Robert A.M. Stern Architects, LLP.

Hotchkiss residence halls. Robert A.M. Stern Architects, LLP.When electricity was first introduced into buildings in the late 19th century, it had a drastic effect on the way that people lived, eliminating dirty and ineffective gas lighting, and enabling a variety of new appliances such as fans, electric irons, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, and washing machines. This was a domestic revolution. But the effect on architectural style was slight. Similarly, if so-called green techniques permeate architecture—as they should—they will likely be invisible. This pair of residence halls (slated to open in September) at the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Conn., was designed by Robert A. M. Stern Architects in the Georgian style, and also happens to achieve a 55 percent energy savings as compared with conventional construction. The buildings use efficient mechanical equipment, high-performance glass, high-efficiency lighting, heavy insulation, and a heat exchanger for exhausted air. Openable windows reduce air conditioning (as they always have). The fact that the Georgian style requires a lot of solid brick walls adds to the energy effectiveness.

-

Genzyme Center atrium. Courtesy Genzyme Corporation.

Genzyme Center atrium. Courtesy Genzyme Corporation.The Genzyme Center, an office building in Cambridge, Mass., is even greener than the Hotchkiss dorms. The coolly corporate design is by Behnisch, Behnisch & Partners of Stuutgart, Germany. The 12-story central atrium maximizes daylighting in the building (more natural light means fewer electric lights and lower air conditioning), and the atrium skylight catches and reflects sunlight. The atrium serves as the major social space of the building and encourages interaction between employees. The building received the ultragreen Platinum LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating from the U.S. Green Building Council, which seems to have cornered the green certification market. But more important, Genzyme Center looks like a nice place to work.

-

Left:CREDIT: 7 World Trade Center. Photograph licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5, courtesy www.wikipedia.org. Right: Hearst Building. Image courtesy Nigel Young/Foster and Partners.

Left:CREDIT: 7 World Trade Center. Photograph licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5, courtesy www.wikipedia.org. Right: Hearst Building. Image courtesy Nigel Young/Foster and Partners.These buildings both claim to be Manhattan's first green skyscraper (both received a Gold LEED rating). That argument aside, their differing architecture highlights the disconnect between architectural style and greenness. Foster & Partners' Hearst Building (far right) has an unusual silhouette, thanks to the diagrid structural system, which is said to reduce the amount of structural steel by 20 percent. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill's 7 WTC is more conventionally boxy and achieves its greenness by using highly transparent glass (to increase daylighting), creating better interior air quality, and conserving water. Both buildings use the full array of green techniques, but neither lets greenness get in the way of good design.