Healthier by Design

-

Image courtesy PictureArts.

Image courtesy PictureArts.There is no place as disheartening as a hospital. Not only because a hospital visit most likely means that you—or someone you care about—are sick but also because of the atmosphere and surroundings: bureaucratic, impersonal, disorienting. And usually ugly. Most hospitals are as utilitarian as bus terminals, with confusing corridors, plastic floors, harsh fluorescent lighting, tired plants. They are charmless places that seem calculated to drive even the healthy to despair.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.In 1995, Maggie Keswick Jencks was dying of breast cancer in an Edinburgh, Scotland, hospital. She and her husband, Charles Jencks, a well-known architectural critic, talked about how the hospital environment affected the physical well-being not only of cancer patients but also of their families and friends. They imagined an addition to the cancer ward: small centers adjacent to cancer-treatment hospitals that could provide nonmedical care—mostly support and information—in a less institutional setting. The first of what came to be called Maggie's Centres was designed by Richard Murphy Architects in a renovated stable next to Edinburgh's Western General Hospital (right). It opened in 1996, shortly after its namesake's death. In a typical year it serves as many as 3,000 new visitors—equally divided between cancer patients and their caretakers.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.The term supportive environment makes me think of those hideous schools of the 1950s whose interiors were uniformly painted green because some researcher had found that the color had a calming effect on children. That is not the approach of the Maggie's Centres, now established as a charitable trust. The assumption, rather, is that a "good" environment results from "good" architecture—that is, architecture created with a sense of conviction. The Highlands center in Inverness, Scotland (right), was designed by David Page of Page & Park. What sets this warm, light-filled space apart from the generic, self-effacing interiors of most health facilities is the high quality of its finishes and details. Not a single vinyl floor tile or fluorescent tube in sight.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.Highlands stands on the grounds of Raigmore Hospital. The landforms in the foreground are part of a landscape designed by Charles Jencks himself, a recognition that gardens can play an important role in relieving stress. The garden has some of the look of a folly, as does the building. This is probably intentional. The last thing that cancer patients and their families need is more grim reality. Though this is not spelled out in the Maggie's Centres' literature, the playfulness of this architecture seems calculated to offset its strictly functional requirements—imagination, these buildings say, can be an important part of the healing experience.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.Jencks turned to Frank Gehry and his firm to design a center at Ninewells Hospital, Dundee (the architect, a close friend of Maggie's, waived his fee). There are said to have been more than 70 models built during the development of the tiny 2,000-square-foot building. The result is a complex composition of juxtaposed forms—and not a billowing sail in sight. Frank Gehry once designed a summer camp for children with cancer. The unbuilt result was both unsentimental and evocative, rather like this building. Unlike some of his flashier work, it attests to the architect's ability to empathize with a program and a site.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

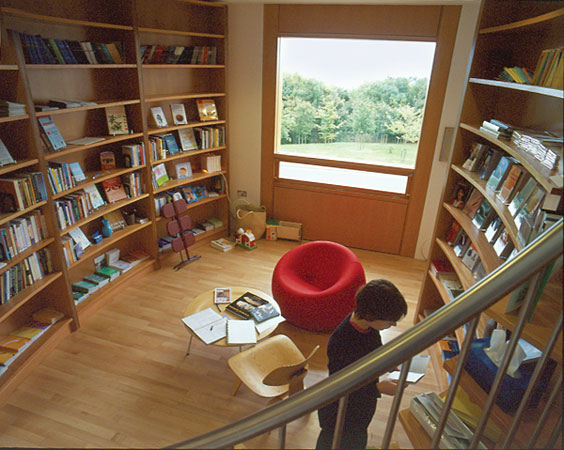

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.The Dundee center overlooks the Firth of Tay, and the tower is meant to suggest a lighthouse. It contains a small library and information area (right). The building also houses a communal kitchen, a therapy room, and private meeting spaces. As in many Gehry designs, the exterior does not prepare one for the interior, which is homelike and even cozy. The intention is to create a place that is both communal and private, institutional and domestic. The architecture is not merely supporting but also challenging. There's a lot of wood and many unexpected views of the surrounding landscape.

-

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.

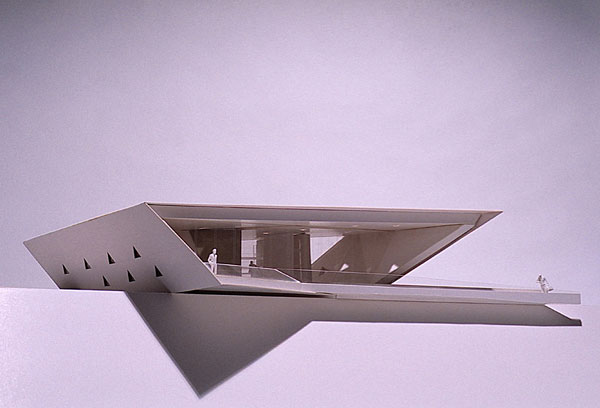

Image courtesy Maggie's Centres.There are currently four Maggie's Centres, with eight more in various stages of development by architects such as Piers Gough, Richard McCormac, and Daniel Libeskind. Zaha Hadid's design in Fife, Scotland, is nearing completion. The model (right) incorporates her characteristically aslant geometry. The aggressive wedge shape seems an odd choice for a caring center, but perhaps I am being too literal. Jencks' long association with A-list architects has obviously helped him corral these stars, which lays him open to the unfair charge that this is merely a vanity project. But why shouldn't good architects be challenged to design small but meaningful buildings? Incidentally, the extra cost of the "architecture" is borne by private fund raising; Maggie's Centres are open to all, free of charge under the United Kingdom's National Health Service.

-

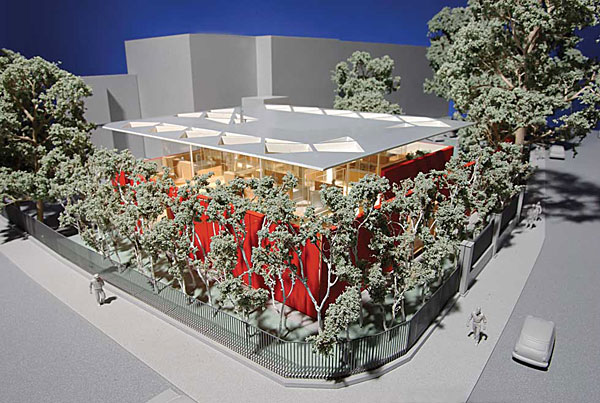

Image courtesy Richard Rogers Partnership.

Image courtesy Richard Rogers Partnership.The first centers were all built in Maggie Jencks' native Scotland, but work is about to start on a center at Charing Cross Hospital in London. Designed by the Richard Rogers Partnership, the building will be covered by a sort of floating roof and insulated from the adjacent noisy streets by a surrounding wall and a blanket of trees. The plan includes several inner courtyards. The open and flexible interior, organized around a two-story-high common kitchen, is light and airy, like most of Rogers' buildings. One lesson of Maggie's Centres is that architectural talent is too precious to be confined to cultural monuments and—in Lord Rogers' case—high-end office buildings. It's nice that art museums and corporations have great architecture, but it would be nicer—and much more valuable for most of us—if hospitals had it, too.