The Stunning Architecture of Spain

-

Guggenheim Museum (Gehry Partners) © Jeff Goldberg/Esto.

Guggenheim Museum (Gehry Partners) © Jeff Goldberg/Esto."On-Site" is the fashionably obscure title of the current Museum of Modern Art exhibition on new architecture in Spain. How new? The show features projects that are either under construction or were completed in the past eight years. That coincides with the opening of what, for most Americans, must be the benchmark of modern Spanish architecture: the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao (at right). Of course, there was notable homegrown architecture at the 1992 World's Fair in Seville and the Olympic Games in Barcelona, but it was Frank Gehry's titanium artichoke that put the country squarely in the international spotlight. Although "On-Site" is an architectural version of New York City's Fashion Week—long on visual excitement, short on intellectual content—there are plenty of projects worth examining.

-

Santa Caterina Market (EMBT Miralles Tagliabue Arquitectes Associats). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Santa Caterina Market (EMBT Miralles Tagliabue Arquitectes Associats). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Was Bilbao, as architects call the museum, a hard act to follow? Not if you were Enric Miralles, the most rambunctious—and most original—of Gehry's Spanish godchildren. Miralles, who died in 2000 when he was only 44, learned an important lesson from the magus of Santa Monica: Take risks. When he succeeded, as with the Igualada Cemetery Park in Barcelona (designed with Carme Pinós), the result was sublime, and even when he did not, as with his last project, the flawed new Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh (designed with Benedetta Tagliabue and RMJM), the effort was nevertheless audacious. Miralles and Tagliabue are represented in the MoMA show by a rather forbidding office complex in Barcelona, and by the Santa Caterina Market in an old quarter of the same city (at right). The multicolored undulating roof, which envelops part of a rebuilt 19th-century building, would be obnoxious if it weren't so good-humored.

-

Metropol Parasol (J. Mayer H.). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Metropol Parasol (J. Mayer H.). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Spain has been remarkably hospitable to foreign architects, as city after city strives to replicate the so-called Bilbao effect, which has attracted millions of visitors to the northern Basque port. Cadiz has Herzog & de Meuron, Córdoba has Rem Koolhaas, Durango has Zaha Hadid, and Valencia has Foster & Partners. One of the most ambitious of the signature projects is a piece of urban infrastructure designed for Seville by Berlin-based architect Jürgen Mayer H. (at right). The six giant connected umbrellas will stand in a medieval square, below which stands a museum and Roman ruins. The mammoth gridded canopy contains a restaurant and roof terraces. The ominous forms, which have none of the whimsy of the Santa Caterina market, recall the AT-AT walkers in The Empire Strikes Back. Whether these cold monoliths will become a tourist attraction remains to be seen.

-

Torre Agbar (Ateliers Jean Nouvel with b720 Arquitectos). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Torre Agbar (Ateliers Jean Nouvel with b720 Arquitectos). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Seville intends its giant parasol to be what architectural critic Charles Jencks has called an iconic building. An architectural icon—think of Wright's Guggenheim Museum—must surprise, shock, intrigue, and seduce, appearing both odd and familiar, off-putting and friendly. Above all, it must appeal to—and attract—a large public. Jean Nouvel's striking 466-foot Torre Agbar may eventually turn out to be as emblematic of Barcelona as Antonio Gaudí's famous Sagrada Familia cathedral, although the purposeful facade of glass louvers appears to have no function except to shimmer prettily at night. Nouvel's design resembles Foster & Partners' Swiss Re headquarters in London, the famous "gherkin," but without that exceptional building's technical invention.

-

Barajas Airport Terminals (Richard Rogers Partnership and Estudio Lamela). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Barajas Airport Terminals (Richard Rogers Partnership and Estudio Lamela). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Since joining the European Union in 1986, Spain has received nearly $110 billion to improve its transportation infrastructure: highways, bridges, railway terminals, and subway stations. The largest of these projects is the newly completed expansion of Madrid's Barajas Airport, designed by the Richard Rogers Partnership and Estudio Lamela. Rogers, the co-designer of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, pioneered high-tech, and the mile-long terminal has all the earmarks of that style: dramatic structure, zoomy sci-fi details, and plenty of exposed bolts. The technical wizardry is handled with a light touch, however, and never overwhelms the architecture. Brightly colored spars support a modular steel roof covered by an undulating bamboo ceiling. It looks unexpectedly jolly.

-

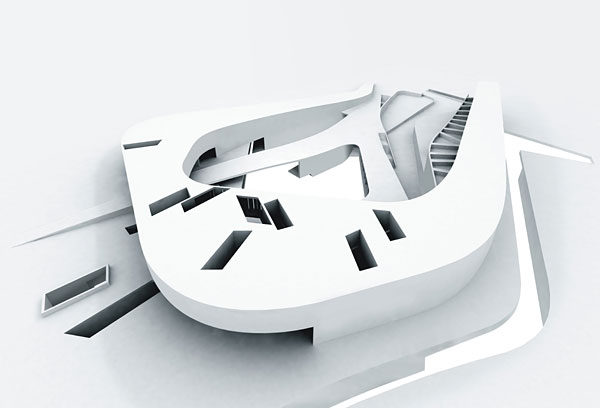

Centro de Talasoterapia (Francisco Leiva Ivorra and grupo aranea). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Centro de Talasoterapia (Francisco Leiva Ivorra and grupo aranea). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Ever since Philippe Starck designed the decor for the Royalton in Manhattan, high-design boutique hotels have become international fixtures. Perhaps the ultimate example is Madrid's Hotel Puerta América. Each of the 12 floors is the work of a different architectural star: Nouvel, Hadid, Foster, and so on. The Puerta América is not in the MoMA show, but three other boutique hotels are. Frank Gehry and Edwin Chan have designed a winery hotel in Rioja that is a pile of cubes swathed in colored titanium ribbons. A hotel in Barcelona is draped with a mesh of solar-powered LEDs that will probably be spectacular at night but may look like camouflage netting in the daytime. Francisco Leiva Ivorra and grupo aranea have designed a hotel and spa in Gijón, on the Bay of Biscay, in the sculptural, monolithic style popularized by Zaha Hadid (at right). The design is very beautiful, although it may be difficult to translate the model's pristine perfection and molded continuous surfaces into actual building materials.

-

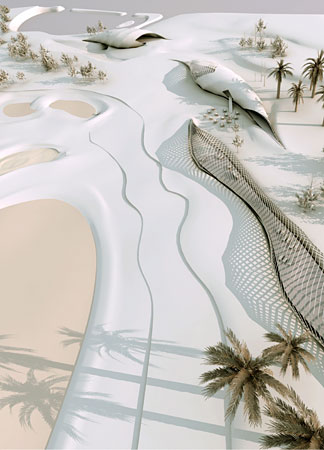

Relaxation Park (Toyo Ito & Associates). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Relaxation Park (Toyo Ito & Associates). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Perhaps the most sublime design in the show is another spa, located in Torrevieja on the Costa Blanca and designed by the Japanese architect Toyo Ito (at right). The site, next to an inland lake, was landscaped by Ito to resemble a sand dune. The three structures, which contain baths, dining facilities, and a reception area, are built of steel and wood, covered, in some cases, by plywood roofs. The skeletal forms recall either shells or some sort of animal: the giant worm in Dune? The entire setting is magical—a thinking person's theme park.

-

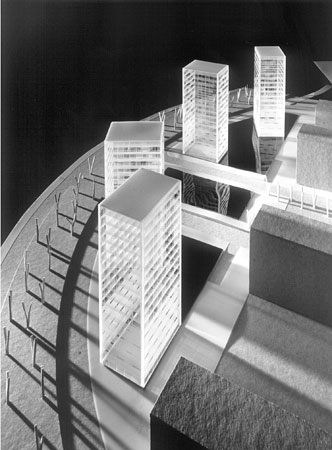

Bioclimatic Towers (Ábalos & Herreros). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Bioclimatic Towers (Ábalos & Herreros). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Clearly, there are interesting buildings going up on the Iberian peninsula, but it's a shame that "On-Site" provides so little information about the architecture. Rarely is the context mentioned, the plans are postage-stamp-size, the descriptions sketchy. Intricate designs, such as Peter Eisenman's ambitious 52-acre cultural complex in Santiago de Compostella, are presented so summarily that one is not enlightened, merely perplexed. The projects are paraded like models on a runway—they appear, walk, turn, disappear. The result is an unfortunate homogenization of radically different work. We are asked only to admire, not to think. The relationship—or its lack?—between the imported stars and local designers is left unexplored. It is unclear what guided the selection of the 53 projects. There's not one building by Santiago Calatrava, who is, after all, Spanish, but there is much work that, while it appears competent, does not break new ground (at right).

-

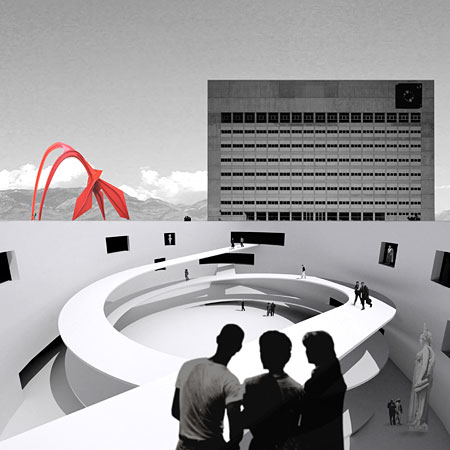

Museum of Andalusia (Estudio Arquitectura Campo Baeza). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.

Museum of Andalusia (Estudio Arquitectura Campo Baeza). Image courtesy MoMA, New York.Perhaps because there are so many assertive buildings strutting down the runway, I was drawn to a couple of the more modest projects. They are easy to miss. The Portuguese Pritzker Prize winner, Álvaro Siza, has built a small and wonderfully understated apartment and office building in an old part of Granada; it is both modern and contextual—no mean feat. The projected Museum of Andalusia, likewise in Granada, by Madrid-based Alberto Campo Baeza, is another deceptively simple design. The partly underground rectangular building surrounds an ellipsoidal outdoor court. From the court, one sees the facade of a bank building (at right) built by Campo Baeza five years earlier. On the other side, an eight-story administrative slab shelters the museum from a nearby elevated highway. This straightforward composition is enlivened by two ramps that overlap and spiral within the court, providing a sculptural foil to the rigorous rectangular geometry of the building. It's all done without fanfare and with great skill.