Frank Lloyd Wright's Beth Sholom Synagogue

-

© Catherine Karnow/Corbis.

© Catherine Karnow/Corbis.The contemporary phenomenon of designing eye-popping museum buildings as tourist attractions is called the "Bilbao Effect," a reference to Frank Gehry's effervescent Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. But the first art museum whose architecture outshone its collection was the original Guggenheim in New York, built by that other Frank … Lloyd Wright. Not everyone admired the concrete spiral on Fifth Avenue when it opened to the public on Oct. 21, 1959. Robert Moses said it looked like an "inverted oatmeal dish and silo." Curators complained about the in-your-face design. The art critic of the New York Times wrote that Wright had managed to reduce art to an "architectural accessory." Even Lewis Mumford, who admired Wright, found that the building overwhelmed the art. He called it an "audacious failure." None of this dissuaded the public. On the first Sunday after the museum opened, 10,000 people lined up to get in.

-

CREDIT: © 2005 Jeff Millies, Hedrich Blessing. Photograph courtesy Price Tower Arts Center.

CREDIT: © 2005 Jeff Millies, Hedrich Blessing. Photograph courtesy Price Tower Arts Center.Wright died six months before the Guggenheim opened. During the last decade of his life, his popularity was at its zenith. He built more than 80 private residences, known as "Usonian houses," his answer to Americans' need for affordable suburban homes. He also designed several large buildings such as the striking Price Tower in Bartlesville, Okla. (at right). The 19-story high-rise, completed in 1956, was his spirited riposte to Mies van de Rohe's steel-and-glass apartment buildings, which had just gone up on Chicago's Lake Shore Drive. The Price Tower, which was designed to be a combination office building and apartment building, is all expressive, thrusting verticality, quite different from Mies' boxy bird-cages. It is a remarkably fresh work for an architect then almost 90 years old. So is the third masterpiece of that fecund period: the Beth Sholom Synagogue. Beth Sholom has always been overshadowed by the Guggenheim, but it is in many ways a better building, and worth a closer look.

-

Photograph courtesy the author.

Photograph courtesy the author.Since Wright's day, architectural modernism has taken many forms—functional, technological, brutal, even sculptural. But this curious combination of geometry and romanticism is Wright's alone. The glass-roofed temple, which was intended to evoke Mount Sinai, towers above the suburban houses of Elkins Park, outside Philadelphia, like a prehistoric ziggurat—or is it a spaceship? Wright manages to make the building look both ancient and futuristic. Either way, it clearly does not belong to our time, and not because it was built almost 50 years ago. Philip Johnson once cheekily described Wright as "the greatest American architect of the 19th century." In the heyday of the International Style, Wright appeared slightly old-fashioned; today I'm not so sure. He was certainly out of the mainstream, but his idiosyncrasy makes him look more forward-thinking than some of the most orthodox modern minimalists—whose buildings he used to call "flat-chested"—and the postmodernists who followed.

-

Photograph courtesy the author.

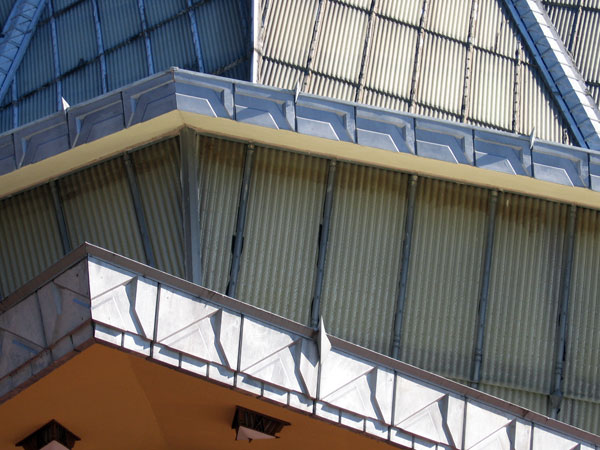

Photograph courtesy the author.Adolf Loos' famous dictum "ornament is crime" was taken as gospel by modernist architects, but Wright never saw a conflict between modern architecture and decoration. Although the Guggenheim is largely devoid of ornament—perhaps out of consideration for the art?—Beth Sholom is richly decorated, inside and out. Light sconces, door handles, even ventilating grills display the abstract geometrical patterns that are a Wright trademark. The stamped aluminum fascias and cornices (at right) introduce the sort of visual detail that makes Gothic architecture, say, so delightful. As in medieval cathedrals, the ornament sometimes has a symbolic role. The jagged silhouettes that enliven the roof transform the three ridges into seven-branched menorahs. Seen at a certain angle, the triangular ceiling lights form sparkling little Stars of David. Wright, a Unitarian, worked hard to incorporate Jewish symbols, and this sensitivity to function is one of the things that makes Beth Sholom a greater work of architecture than the Guggenheim.

-

Photograph courtesy the author.

Photograph courtesy the author.Although Wright's client, Rabbi Mortimer J. Cohen, told Wright that he wanted the synagogue to be a "new thing," Wright had been thinking of such a religious building for a long time. In 1927-28 he designed an interfaith cathedral for 100,000 worshipers. The visionary project, an enormous steel-and-glass building that would have been the tallest structure in the world, was never built, but its pyramidal form resurfaces at Beth Sholom. The glass roof encloses a columnless, hexagonal sanctuary to create a religious space that has no historical precedent. The floor, nowhere level, slopes gently to form a huge bowl, giving the impression that the 1,100 congregants are sitting in a natural amphitheater under a huge glass tent. The individual padded seats are comfortable—unlike much Wright-designed furniture. The theater seating and the auditoriumlike arrangement anticipate the megachurches of a later period, but there is nothing secular about this numinous space. We are, as Brendan Gill once put it, "in the presence of a Presence."

-

Photograph courtesy the author.

Photograph courtesy the author.The bimah, a platform from which the Torah is read, is located at the lowest point in the sanctuary. Above and behind the curtained wooden ark, which contains the Torahs, Wright—at Cohen's request—created a striking ornament (at right). The geometrical forms, of gold aluminum and crimson and yellow glass, represent God's presence surrounded by seraphic wings, a dramatization of the sixth chapter of Isaiah. The Hebrew word kadosh (sacred) appears three times, referring to the Biblical quotation "Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, the whole Earth is filled with His glory." Wright's ability to seamlessly integrate such literal symbolism into his otherwise abstract design separates him from conventional modernists, who have always struggled, usually without success, to incorporate meaning into their buildings. Just think of Mies van der Rohe's chapel at the Illinois Institute of Technology (built at the same time as Beth Sholom), which some have compared to a boiler house, or Rafael Moneo's recent Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, whose figurative artworks are at odds with the abstract architecture.

-

Photograph courtesy the author.

Photograph courtesy the author.Wright called his architecture "organic." It is this naturalistic quality that underlines the difference between his approach and that of most contemporary architects. Norman Foster and Renzo Piano, for example, are meticulous craftsmen whose buildings exhibit a machinelike precision. The buildings of Thom Mayne and Gehry, while whimsical, are likewise mechanical and sometimes look like machines run amok. The synagogue is not like that at all. It is modern, but it also belongs to nature. The great steel tripod that supports the roof (at right) does not evoke engineering but rather a skeleton or a tree. The dull gray patterned aluminum and the creamy corrugated fiberglass are produced industrially, but they do not make us think of factories or machinery. Contemporary architects tend to celebrate details and materials for their own sake: mesh, patterned zinc, stretched cables. Wright never let the way that his architecture was built interfere with its essence. Which is how it makes us feel.