The Om Factor

-

After Frank Gehry's stunning Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, opened to universal acclaim in 1997, midsized cities around the world raced to build their own architectural tourist attractions. The thinking was simple: As long as a new building is enough of a spectacle, visitors will show up in droves. There are plenty of subtleties in Gehry's design—mostly in terms of how carefully it relates to the streets and city surrounding it—but nobody flew to Bilbao for a lesson in contextualism. They went to be amazed.

-

In 1999, Seattle hired Rem Koolhaas, the Dutch architect, to design its new downtown public library, set to open early in 2004. Koolhaas produced a monolithic, mesh-covered, quasi-Mayan scheme worthy of any city's tourist brochure cover. Denver, Toronto, and Manchester gave post-Bilbao museum commissions to Daniel Libeskind, the now-famous winner of the Ground Zero competition, who delivered a trio of predictably dramatic and photogenic projects. His extension to the Denver Art Museum, shown here, looks like an explosion captured midboom, with sharply canted wings—faced in glass, titanium, and stone—shooting from the center of the building.

-

Even the biggest cities in the world haven't been able to resist the pull of what architecture critics have dubbed the "Wow Factor." In New York, Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio prevailed in a high-profile competition to design the new headquarters for Eyebeam, a center for art and technology on 21st Street. Their winning scheme calls for a bright-blue folded structure that, for all of its extroverted appeal, risks looking dated as soon as it's finished.

-

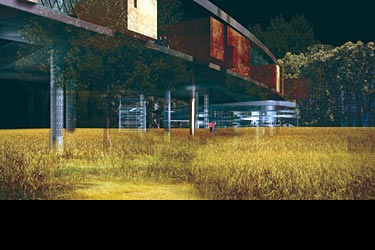

Gehry took the trend to its peak three years ago with this sprawling, 570,000-square-foot scheme for a new Guggenheim on the Lower East Side of Manhattan—which, given the museum's financial woes, probably won't ever be built. Nearly 10 times the size of Frank Lloyd Wright's original Guggenheim on Fifth Avenue, with projected building costs of roughly a billion dollars, the design combined the worst impulses of the museum's expansionist strategy under Thomas Krens and Gehry's own Bilbao-boosted love for huge, oozing designs (see the Experience Music Project).

-

A couple of months ago, the New York Times Magazine devoted an issue ("Tomorrowland") to celebrating the Wow Factor. There was praise for "bold, emphatically forward-looking" and "dazzling" buildings, for architecture that "takes your breath away" and produces "swoopy euphoria." But it was Gehry himself who told one of the Tomorrowland essayists that they were "too late." The trend toward architectural excess, he suggested, is now "dead in the water."

-

This is probably even truer than Gehry realizes. There are signs everywhere that famous architects have become reluctant to embrace spectacle for its own sake. The shift has something to do with the sluggish economy and with a growing backlash against the architectural benders of the 1990s. It's certainly connected to the increasingly crucial role in architecture of sustainability, an ethos that stresses protecting natural resources by doing more with less. Most intriguing, it may be connected to architects' reluctance—conscious or not—to design buildings that stand out as targets after Sept. 11.

-

Whatever the reasons, a number of recently unveiled high-profile, even high-stakes architectural projects—many by architects who usually build more, well, conspicuously—are most notable for the way they retreat from the spotlight. When it comes to new buildings by well-known designers, the tide is turning toward a quieter, more modest, and even introverted brand of architecture. Call it the Om Factor.

-

This new group of buildings is no mere extension of the trendy streamlined minimalism that's filled the pages of Wallpaper and other shelter magazines in recent years. While high-end minimalism usually just pretends to be modest—by using, say, a $5,000 Paola Lenti couch positioned under a $125,000 Agnes Martin print to call attention to one's tasteful restraint—the best examples of Om-chitecture seem genuinely to be so.

-

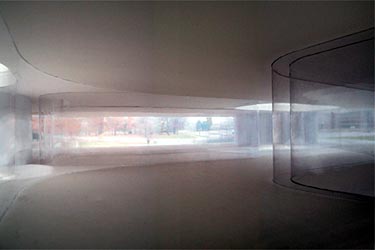

Which invites the question: What is architectural modesty, exactly? Well, it can simply be a rhetorical reaction to oversized, over-exuberant architecture: a spare symbolism of quietude and restraint. More specifically, it has to do with the careful arrangement of forms—often using muted or transparent materials like glass or a restricted palette of colors—to produce a building commensurate with daily life instead of bigger than it. Take the Japanese firm SANAA's elegant, deceptively simple scheme for the Toledo Museum's Center for Glass, which is so unassuming that it practically disappears from view.

-

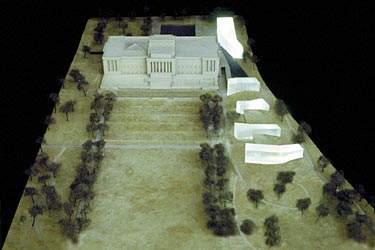

Other examples of the Om style dig underground. This helps reduce their visual impact, especially when the architect is trying to avoid overshadowing existing buildings. In Steven Holl's design for a Kansas City, Mo.*, museum addition, going below ground allows for the introduction of new architecture that's unmistakably new but isn't interested in dominating the site.

[*Correction, Aug. 7, 2003: This museum is in Kansas City, Mo., not the state of Kansas, as the piece originally stated.] -

Another sign of modesty is a willingness to extend existing landmark buildings, or fill in the spaces between them, instead of striking a world-beating pose. This is a design by Foster and Partners for a sort of interstitial addition to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

-

Architectural models and computerized renderings make particularly clear the ways in which architects are choosing to downplay scale and mass—and even ambition itself—in favor of a transparent or vaporous style. This image from the office of French architect Jean Nouvel, for instance, tries to make steel beams look like see-through apparitions. The finished products may not achieve the same sense of lightness as the renderings do, of course; but in terms of gauging architects' intentions and rhetorical priorities, the preparatory images are telling.

-

Because the trend is a young one, at this point the most significant completed examples are older buildings renovated for new public uses. They include Annabelle Selldorf's sublime 2001 design for a small Manhattan museum called the Neue Galerie, which one critic praised by saying, "You could almost call it invisible architecture" (and which I raved about in this Slate piece).

-

Then there's the new Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, which opened in March and occupies the city's former main library. The 1917 Beaux Arts building has been smoothly updated by the Italian architect Gae Aulenti, in a design that carefully balances boldness and restraint.

-

The recently opened Dia: Beacon art center in upstate New York is an old Nabisco factory renovated by the firm OpenOffice and artist Robert Irwin that takes modesty to its furthest point—architectural anonymity. While the Guggenheim in Bilbao burst onto the scene as the capstone to an architectural genius's long career, Dia has promoted its new branch as essentially undesigned—which is a pretty radical strategy in the competitive world of museum architecture. The press images of its empty, well-scrubbed galleries are completely devoid of noticeable architectural gestures.

-

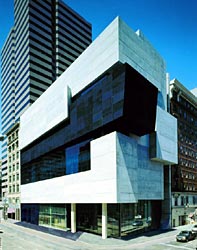

Even Zaha Hadid, the Iraqi-born, London-based architect once known for designs of dizzying complexity and obstinate illegibility (few were ever built), seems to have embraced the Om worldview. She recently told the Wall Street Journal that her goals as an architect have shifted, and that "the bottom line now is well-being. In the end, architecture should be about people feeling good in spaces." Her ambitious new Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, which just opened in Cincinnati, adds a calmer and more thoughtful presence to the downtown cityscape than anybody might have anticipated.

-

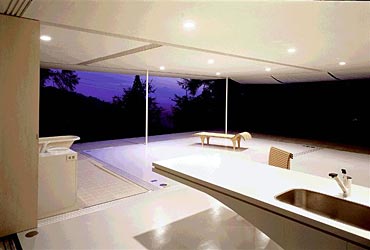

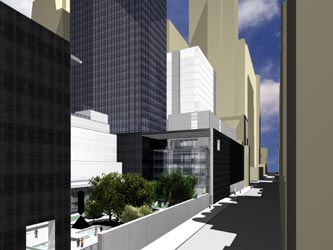

Several significant examples of the trend, including two of the most anticipated new buildings to go up in New York in ages, are still on the drawing board or under construction. One is Yoshio Taniguchi's extension to the Museum of Modern Art, set to be finished in two years. Despite the fact that it includes 630,000 square feet of new and redesigned space, Taniguchi's design is more interested in throwing a flattering light on the museum's collection of art—and on its existing campus of buildings—than in advertising itself.

-

This is a scheme that slips so easily into the voids between buildings that it begins to seem more like a liquid than a solid. The design is tremendously sure of itself, but in a quiet, even accommodating sort of way; its modernism is the opposite of domineering. Taniguchi has described it, perhaps a bit severely, as "disciplined." Significantly, this is a project that helped kick off the Om trend: The Modern chose Taniguchi over several architects who could have been expected to produce a sexier addition, including Koolhaas, Bernard Tschumi, and the Swiss duo Herzog and de Meuron.

-

See, too, the new headquarters for the New York Times, by the Italian architect Renzo Piano. Piano uses a series of ceramic screens to play up the building's ethereal, light-on-its-feet quality and to mask its size. It's worth noting that the Times and MoMA can rely on institutional prominence to win attention for their schemes—and that also means that they can risk commissioning more subtle architecture without sacrificing necessary PR value. (Neither of these designs, though, is particularly modest in size or cost: The price tag on the Modern's addition now reads $850 million.)

-

Still, Piano's plans for the Times suggest that an inward-looking architecture can succeed aesthetically on a huge scale: At least in model form, the building looks wispier, and more graceful, than you'd think any 52-story skyscraper possibly could. By the time it's completed—about three years from now, according to the paper—we may not have forgotten about the Wow Factor altogether. But it will probably seem as outdated as any number of relics from the 1990s, from a high-flying Nasdaq to a sense of ironclad American invulnerability. It took a few years, but we finally have an architecture that reflects just how far gone those days actually are.