A Low-Key High Modernist

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

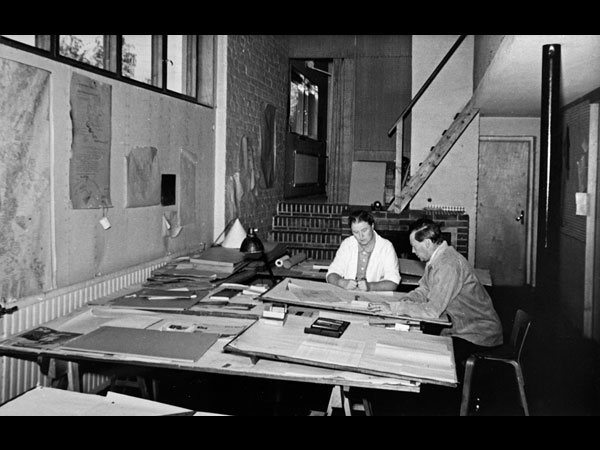

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.This 1941 photograph shows the Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto, with his wife and collaborator, Aino, in the studio of their home outside Helsinki. Like all the main rooms in the house, which they designed themselves, the studio has a cozy fireplace, just visible in the background. Aalto, who belonged to the first generation of International Style modernists, was not a polemicist like Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, and he produced buildings that have stood the test of time, not only because they were well conceived, but also because they were well built. As a new, beautifully illustrated book on Aalto's houses (many of which are less well known than his public buildings) shows, his domestic work bears revisiting, for his particular brand of low-key modern design holds many lessons, especially in our economically stressed period.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.While many of the modernist pioneers were not formally trained as architects—Behrens and Van de Velde studied painting, Mies van der Rohe was a builder's apprentice, Le Corbusier learned watch-engraving—Aalto (born in 1898) studied architecture at the University of Helsinki. He was taught a severe, Nordic version of classicism, and one of his first commissions (right), a country house, has vertical wooden siding and a low, hipped roof, more like a Finnish farmhouse than a neo-classical villa. The plan resembles an American center-hall Colonial, with formal public rooms on the right and the kitchen and a traditional tupa (a multipurpose room) on the left. An unheated vestibule, covered in stucco, occupies the center of the perfectly balanced façade. Aalto would soon abandon this style, but he would never stray far from the practical traditions that a cold climate—and conservative customs—demanded.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

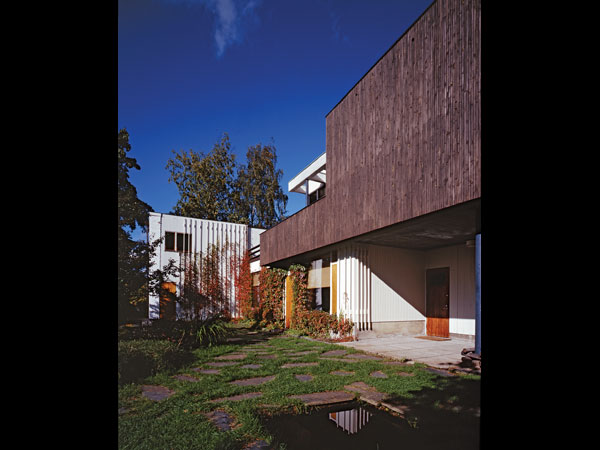

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.While most European modernists were building suburban villas, Aalto was soon given the opportunity to build industrial and public buildings in the newly independent Finland. By the mid 1930s, he had achieved international fame with a modern-looking newspaper plant, a streamlined tuberculosis sanatorium in a northern forest, and a public library. In these buildings he adhered more or less to the International Style, but in the home and studio that he and Aino built for themselves in Munkkiniemi, a distant suburb of Helsinki, they explored a different sort of modernism. Instead of white Cubist boxes, they created a collage of lime-washed brick and several different textures of wood siding, some painted white and some dark brown. The office-studio on the left is enlivened by a screen of vertical rods for climbing plants. There is nothing functionalistic about this architecture—the dark wall morphs into a balustrade at the roof terrace. Leaky flat roofs were a hallmark of the International Style, but here and in other projects Aalto's common sense prevailed and the roofs are actually gently sloped.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.The Aaltos didn't just design buildings, they also designed lamps, furniture, and fabrics. The living room of the Aalto house, today owned by the Alvar Aalto Foundation (and open to visitors by appointment), contains many examples of their work. The easy chairs are strikingly modern, but instead of tubular metal and leather, they are made out of bent wood and upholstered in fabric, a characteristic combination of innovation and tradition. The furniture was manufactured by the Artek company, which still carries many Aalto designs, including his famous stool, a low-cost version of which is available from Target. This furniture has withstood changing fashions by providing tactile pleasure as well as comfort.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.Alvar and Aino Aalto designed many small houses in the 1930s, but their masterwork was a large country residence for a young couple, Harry and Maire Gullichsen, part of the family that owned the A. Ahlström industrial conglomerate, for which Aalto designed factories and worker housing. The so-called Villa Mairea is a curious blend of white-box modernism, handcrafted details, and a rambling casualness. The white walls are not hard-edged plaster such as European modernists used but lime-washed brick. Although this is a rather grand house, it has a bourgeois sense of unpretentious comfort, which sets it apart from contemporaneous modernist country houses such as Mies' Tuggendhat House in Brno, or Le Corbusier's Villa Savoie in the Paris suburbs.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.The main living space demonstrates Aalto's odd brand of modernism, which is rooted in tradition. (Aalto's traditions were always authentic, however, never used coyly or whimsically, as in the later postmodern movement.) Living room, dining room, and art gallery—Maire Gullichsen collected modern art—are combined in a single multipurpose space, with a library area defined by movable bookcases. At the same time, there is a traditional Finnish raised fireplace in the corner, a beech-wood ceiling, and the tubular steel columns are wrapped in rattan. Sculptural staircases were a common feature of early modern houses, but the wooden stair of the Villa Mairea, with its handcrafted details is far removed from a "machine for living."

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.Like most early modernists, Aalto was fascinated by the idea of factory-produced housing, but he approached the problem in a characteristically unmechanical way. His standardized housing "system" comprised prefabricated doors and windows and precut lumber, but these were combined to create the maximum variety. Aalto was active in Finnish postwar reconstruction, and among his projects was a small development of 26 semidetached houses for veterans in the small city of Tampere (right). The modest (2 rooms and a kitchenette) houses are not an exercise in self-indulgent design, but rather a practical solution to inexpensive and simple shelter—the houses were built by volunteers. These modest bungalows—still in good shape—gain character from the tarred-log porch supports.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.One of Aalto's most charming designs of the immediate postwar period is this small hunting cabin. The one-room structure, with an attached sauna, has a turf roof, spruce tree-trunk columns, and rough wooden gutters. While some of these features are the result of material shortages, it is hard not to see this and other Aalto houses of that period as exercises in deliberate normality. After all, Finland had just fought three wars, successfully resisting a Russian invasion in 1939-40, fighting the Soviet Union, and then Nazi Germany. Visionary modernism may have seemed out of place.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.During the late 1940s and 1950s, Aalto garnered many international commissions, among them the Baker Dormitory at MIT, apartment buildings in Germany, and an art museum in Aalborg, Denmark. The Säynätsalo Town Hall in central Finland is a masterpiece of this period. So is the house (right) that Aalto design for the Parisian art dealer, Louis Carré, in Bazoches-sur-Guyonne, near Versailles. Carré told the architect that he wanted "materials that have lived" and a "real roof," and that he didn't want anything luxurious. The result was a modern villa of whitewashed brick, copper, and travertine, topped by a sloping slate roof. Simple yet extremely elegant.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.Both elegance and a lack of luxury are visible in Louis Carré's bathroom, which is finished in gray ceramic tile rather than marble, and is equipped with wooden rather than stainless steel handrails. A stark contrast to the Pompeian extravagance of many high-end bathrooms today.

-

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

From CREDIT: Alvar Aalto Houses by Jari Jetsonen and Sirkkaliisa Jetsonen – Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.Aalto spent part of World War II in the United States, where he met and became friends with Frank Lloyd Wright (Wright, on seeing Aalto's Finnish pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair, had declared the Finnish architect a "genius"—a rare compliment) and Aalto's use of exposed brick was influenced by Wright. While late in his career Aalto focused on large public projects such as theaters and opera houses, he designed several small houses for friends. He believed that a house should reflect the character of its owner, and this small, polygonal-shaped summer lakeside cottage for a professor of classical languages includes a book-lined work space in the corner. Unaffected pine boards are used throughout the interior, which includes lamps and furniture designed by the architect years earlier and still fresh. The unpretentious house, completed in 1974, just two years before its architect's death, cannily combines modern ideals with a down-to-earth realism in a way that has rarely been surpassed since.