What Happened After New Orleans Fired All of Its Teachers—and Why It Still Matters to Diversity in the Classroom

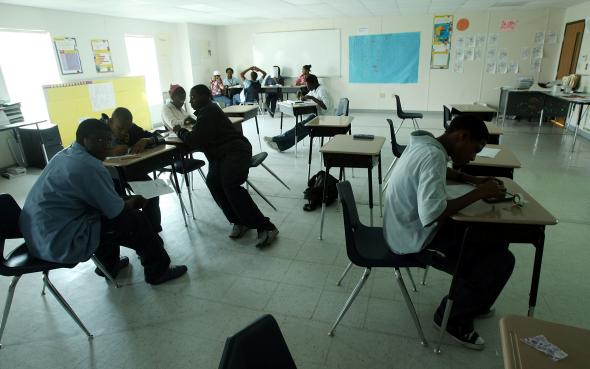

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

About seven months after Hurricane Katrina devastated large swaths of New Orleans and decimated scores of the city’s schools, the Orleans Parish School Board fired all 4,600 of the city’s public school teachers, most of them black. The firing was part of an effort led by key state officials to reinvent the city’s long troubled schools as independently operated charters, complete with new leadership and a new approach. But as a result, a core part of the city’s black middle class lost work, and the demographics of the city’s teaching corps have shifted significantly in the decade since—from about 71 percent black to just under 50 percent black, according to new figures that Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans released this month. Average experience levels have also declined: In 2005, more than half of the teachers had more than 10 years experience, compared with about 30 percent in 2014. Douglas Harris, the alliance’s director, says it’s likely the single biggest demographic change of any urban teaching corps since the school desegregation of the 1960s and ’70s.

Yet too few people in New Orleans, or anywhere else, are talking about what the shift means, for students (85 percent of whom are black) or for the city as a whole. Many of the fired teachers remain incensed by the way they were treated, and suspicious of the newcomers. Many newcomers, in turn, feel at least mildly uncomfortable that the firing of thousands of veteran black educators precipitated the city’s ambitious school reforms. (Below, you can listen to my report for New Orleans Public Radio on the topic.)

These are not ideal conditions for talking openly about a sensitive subject. Yet the city’s experience over the past decade shows how important it is that we get over our reluctance—at times fear—of talking about teachers and race. In recent years, there’s been a robust conversation about student diversity accompanied by some promising, if very small-scale, efforts. Yet teacher diversity has not engendered the same scrutiny or debate, despite the fact that America’s public school classrooms are, for the first time, predominantly filled with students of color while the teaching corps remains overwhelmingly white.

There are three main reasons we need to talk more about teachers and race: First, it matters. The research body is fairly conclusive that, other things being equal, students learn more when taught by a teacher of the same race. Thomas Dee, a professor of education at Stanford University, used test score data in Tennessee to conclude that spending just one year with a teacher of the same race significantly improves students’ progress in reading and math—for both white and black children. Other studies have concluded that placing students of color with teachers of the same race reduces special education and suspension rates, and increases graduation and college admission rates.

Of course, those “other things” are rarely equal. That’s definitely been the case in New Orleans, where test scores have gone up but just about everything else that could change did change. The teaching corps is whiter and younger. Schools spend more money per pupil, on average, than they did before Katrina; principals at the mostly nonunionized new charter schools have far more autonomy over hiring, curriculum, and calendar; and perhaps most significantly, many of the new school leaders maintain an unprecedented and laserlike focus on data and short-term test score growth.

We will probably never be able to tell just how much race matters. Would the test score growth in New Orleans, for instance, have been even more significant if the new charters had recruited more black teachers, something Teach for America is now doing in New Orleans and nationally? Is it better for a student to have a good teacher of the same race, or a great teacher of a different race? And what matters most: the race of teachers, class size, money, teacher training, or something else?

There’s no one right answer to these questions, and racial solidarity in the classroom probably means more to some students than others. But we know that it means something, and everyone can learn from existing research on the issue. This is the second reason we have to talk more openly about race in the teaching profession: The conversation can help all teachers improve.

Most of the major studies on teachers and race attribute the strength of same-race teachers to specific actions: the ease with which they develop caring and trusting relationships, their tendency to employ culturally relevant curricula and teaching practices, their willingness to confront issues of racism in their teaching. These attributes might come more naturally and effortlessly to black teachers teaching black students, Hispanic teachers teaching Hispanic students, or Native American teachers teaching Native American students. Sometimes, simply existing in the classroom as a teacher of color in a leadership role can inspire ambition in students. But just as white politicians can enact policies that benefit communities of color, so too can any teacher, of any race, strive to build trusting relationships, learn the culture of her students, and openly broach subjects of race and racism. A more diverse staff can help cultivate a schoolwide commitment to these issues.

Third and finally, students notice and care about race in the classroom, and their insights can challenge us all. After seven years reporting on New Orleans schools, I helped commission a series of student essays for the Hechinger Report in 2014. Two of the high school students wrote about demographic changes in the city’s teaching corps after Hurricane Katrina.

Brianisha Frith sang the praises of the mostly “white, young, and fresh out of college” teachers who had worked with her since Katrina. Prior to the storm, she wrote, “the majority of my teachers were middle-aged African Americans. … The notion of college was nowhere implanted in my head.” Later in the essay, she acknowledged that her black teachers had helped her “understand the connection between schools and community” and “become more self-sufficient.”

In stark contrast, Glenn Sullivan expressed concern that “a lot of the good, black teachers were being replaced” in New Orleans. “I firmly believe that having more local teachers and teachers who understand the city’s social and political problems can provide students with the training they need to be successful as students and adults,” Sullivan wrote.

Despite the difference in the students’ conclusions, the essays had notable similarities: Neither student pretended to be colorblind. Nor were they simplistic or deterministic in their conclusions: Sullivan noted that some black teachers struggle just as much as white teachers to gain the respect and attention of students. And Frith, while preferring the college focus of her new teachers, acknowledged the strengths and weaknesses of both groups. Each student associated the race of their teachers with the transference (or lack of transference) of specific values: college ambition, community connection, trust, and respect. But they weighted those values differently.

Race mattered to both students, but not always in predictable, consistent ways. A better understanding of why, and how, it matters for children, particularly the most disenfranchised, could help New Orleans teachers and schools become more effective in the wake of a 10-year-old tragedy. And it could help all educators, everywhere, in their bid to reach and teach a rapidly diversifying student population whose needs and backgrounds are more varied and complex than ever.