As a fifth-grade student in Clarksville, Tennessee, a small city near Nashville, I constantly got in trouble. Just about every day, I came home with a pink slip. I didn’t always know what I’d done wrong. But I knew the pink slips weren’t good and that three of them added up to detention. That’s where I—one of only a few black students at the school—spent countless afternoons.

The teacher, who was white, told my mother that I moved around too much and finished assignments too quickly. The teacher said she didn’t understand me; she suggested I get tested for attention deficit disorder.

My mother had a different interpretation. You were “a black student she couldn’t control,” she told me recently. “She wanted a reason for that.”

I was the child of an Army officer, so we moved around a lot. I attended seven different public schools in six states before leaving home for college. In all, I had just one black teacher: Mrs. Bishop, at MacArthur Elementary School in Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. That year was my strongest academically. I’m convinced there was a reason for that.

Nationwide, we have a teacher diversity problem. This year, for the first time in our country’s history, a majority of public school students are children of color. But most teachers—82 percent in the 2011-2012 school year—are white. That figure hasn’t budged in almost a decade.

The knee-jerk response is to blame the minority teacher shortage on inadequate recruitment efforts. But key data suggests that we also have a largely unacknowledged and unaddressed problem with retention. In other words, our schools are churning and burning teachers of color at unconscionably high rates.

Richard Ingersoll, an education professor and researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, says large-scale teacher recruitment campaigns that began in the 1980s succeeded in doubling the number of nonwhite teachers entering the profession. But disproportionately high turnover rates among teachers of color undermined much of that progress. Between 1988 and 2008, teachers of color were 24 percent more likely to leave teaching than their white counterparts, according to Ingersoll’s research. Some years, more minority teachers left the field than entered it.

And the problem is getting worse, particularly when it comes to movement between schools: The number of teachers of color who left their schools or the profession altogether jumped 28 percent between 1980 and 2009, according to Ingersoll. (The number who left the field altogether increased from 6 to 9 percent over the same time period.)

There are several reasons minority teachers leave schools at disproportionately high rates. For one, minority teachers are more likely to work in high-poverty, low-performing schools where turnover rates are higher among teachers of all races and backgrounds. Working conditions in these schools can be more difficult given the challenge of teaching large populations of high-needs students with insufficient resources and chronic staff turnover. And many federal and local policies over the last two decades have aggravated these tensions—pushing out teachers and principals at “failing” schools or closing them outright, for instance. On top of that, teachers of color often feel isolated or stereotyped, particularly in schools where most of the other teachers are white or come from different backgrounds.

Corinne Bridgewater, who taught in a New Orleans charter school during the 2013–14 school year, left partly because she felt isolated as one of only three black teachers at her school, which rigidly enforced countless rules. One day, for instance, a female student arrived at school wearing a bandana—a contraband item in the school’s uniform code—over her head. When the girl said she couldn’t remove it, Bridgewater immediately knew why: The teen had started removing her synthetic braids the night before—a time-consuming effort—and needed to cover her head until she could finish the process. Bridgewater felt frustrated working at a school where most teachers couldn’t make that connection and therefore wouldn’t let the bandana slide.

White teachers, of course, are not incapable of connecting with students of color.

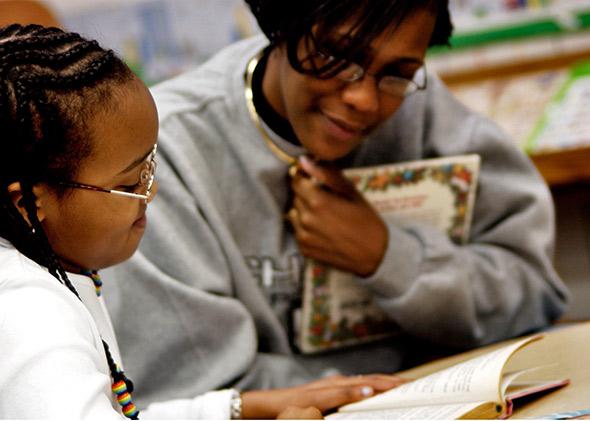

But a significant body of research suggests the benefits of a racially diverse teaching force are considerable. Several studies in the late 1980s and early ’90s, for instance, found that teachers of color can boost the self-worth of their minority students, partly by exposing them to professionals who look like them. As a kid, I saw my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Bishop, for more hours a day than my own mother. She was my mirror. She gifted me an image of myself.

The benefits of keeping teachers of color in the classroom extend far beyond role models. Research has shown that students perform better academically, graduate at higher rates, and stay in school longer when they have teachers who come from the same backgrounds as they do. Esther Quintero, a senior policy fellow at the Albert Shanker Institute, a nonprofit education think tank, says the disproportionately high suspension rates for black students could be alleviated by keeping more teachers of color in the classroom. White students stand to benefit, too: Early interactions with teachers of color can help dispel damaging stereotypes about different ethnic groups.

A diverse teaching staff can also challenge the thinking and assumptions of its members. When the second-grade teachers at New Orleans’ Sylvanie Williams Elementary School settled on Cinderella as the main text for a fairy tale unit, Micaella Glenn, the only black teacher on the team, pushed them to incorporate non-European versions of the tale. The students also read Cendrillion (a version set on Martinique), Yeh-Shen (a Chinese version), and The Rough-Face Girl (an Algonquin telling).

There are countless programs designed at drawing more minority teachers into public schools, but comparatively few focus on supporting them once they get there. A few promising new initiatives aim to counter this trend, however.

In Illinois, where the school system’s teachers are among the least diverse in the country, lawmakers created a combined recruitment and retention program in 2005 that prioritizes teachers of color. Grow Your Own Teachers works with community organizations and colleges to help new teachers get certified, and then supports them with two years of mentorship and training once they’re hired. Eighty-five percent of participants are people of color.

The Boston Teacher Residency provides scores of teachers one-year apprenticeships with veteran teachers, and aims to fill half of their spots each year with people of color. This goal is particularly important in Boston, where a Center for American Progress report found the gap between black teachers and students in the city is so large—21 percent—that the district is in violation of a federal court order for teacher diversity.

And in New Orleans, where the proportion of teachers of color has steadily declined since charter schools began expanding after Hurricane Katrina, Teach for America has doubled down on attracting and keeping young minority teachers in its classrooms. This year, 46 percent of the New Orleans corps, and 50 percent nationally, identify as people of color. The TFA region piloted the Louisiana Ties program, which tries to recruit more New Orleans natives and others with connections to the area—ties that often make them more likely to stay.

And the Collective, TFA’s national alumni association for teachers of color, has also played a crucial role in boosting the number of minority teachers who stay in the classroom. Started in 2011, the group functions as a social safety net: It strives to help combat the isolation that current and alumni minority teachers like Bridgewater sometimes feel—an isolation that can drive them out of the classroom. Members get mentoring and support from colleagues who have experienced similar challenges. The group has also helped TFA’s teachers of color build a public identity, which helps challenge the “messianic, white Ivy Leaguers” image often cited by the organization’s critics.

I know first-hand the challenges—and rewards—of working as a teacher of color. From 2011 to 2013, I was one of two black high school teachers at my alma mater in central Oahu, Hawaii, where I got a job through Teach for America. Most teachers and students at the school are from Asian and Pacific Islander or Polynesian backgrounds. When I was a student there from 2002 to 2006, none of my teachers was black.

I desperately wanted to give my black students something I had lacked during my own student experience: a role model who looked like them. I helped black and other students new to the islands understand, for example, that Pidgin, a Creole language spoken in the Hawaiian islands, is not “broken English,” as it is often described. I pointed to African American Vernacular English, a dialect spoken by some black people, as a similar example. And I defended my students who spoke in either vernacular when their peers and teachers complained about it.

I had conversations that I believe many nonblack teachers would have shied away from. When a white ninth-grade student called her friend the N-word in front of me, for instance, I did not let it pass unaddressed. Instead, we had an awkward but important conversation about the historic significance of the word.

But in the end, teaching couldn’t retain me. Like Bridgewater, I felt isolated as one of only two black teachers at the school. I did not have enough colleagues I felt comfortable turning to, for instance, for advice on how to broach the subject of Trayvon Martin’s killing with my students. Contentious contract negotiations and the uncertainty created by the Common Core and new teacher evaluation systems also heightened my anxiety.

I think often of my black students who, in many cases, will never have a teacher who looks like them. I think of the ways in which even other people of color might stereotype them. I think about a former Polynesian student of mine who was completely immersed in black hip-hop culture yet seemed worried she would offend me by saying my race out loud during a class discussion on immigration and ethnic backgrounds. I saw one of America’s great failures—an inability to teach its children how to talk about race—materialize in the shame on her face as she struggled to say out loud what and who I am.

I also think about the teachers who replaced me. I wonder how long they’ll last, particularly the teachers of color. More than anything else, I worry about what will become of the kids caught in the shuffle.

This story was co-produced with the Hechinger Report.