How to Take Better Food Photos

Recently, I finally gave in and joined Instagram. I got hooked immediately, despite one peculiar discovery: My friends and acquaintances were posting tons of amateur porn—food porn, that is. Breakfasts of lattes and flaky croissants, turkey dinners and half-eaten cookies. I discovered that one dude I know has surprising pastry talents, and that a former co-worker gets off on vegan pilaf. I scanned, liked, and commented on meals and snacks of people I barely knew. Then one morning, waking to a photo of partially consumed meat—something not even an Instagram filter could pretty up—I began to feel uncomfortable. I was reminded of the time I accidentally happened upon a former housemate’s naked photos. I’m sure she had a nice time making them, but why did she have to leave them on the kitchen table? Weren’t we carelessly over-sharing?

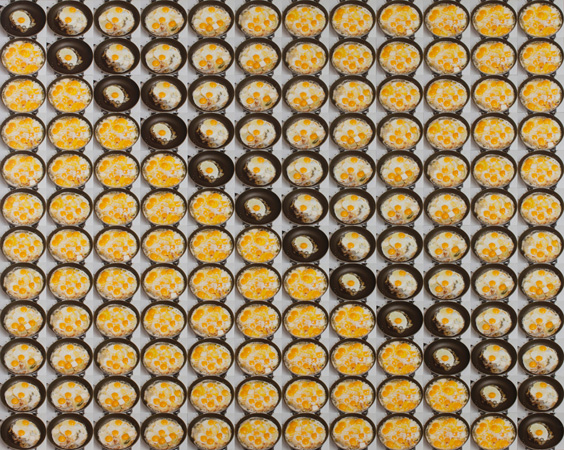

Feast Your Eyes, an exhibit currently on display at powerHouse Arena, is a nod to this growing obsession with documenting what we eat. Every year, the New York Photo Festival holds a contest. This year, directors Dave Shelley and Sam Barzilay selected the theme of food and invited a panel of judges, including Jon Chonko of Scanwiches and Alex Pollack of Bon Appétit, to pare down dozens of entries from professionals and amateurs alike.

One of the most striking photos is a simple portrait of a beet against a black backdrop—not any beet, mind you, but a truly genius veggie. (Really: It was grown by Cheryl Rogowski, the first farmer to receive a MacArthur “genius grant.”) The picture was taken by Kevin Ryan, who says he approaches vegetables much like he does people, making sure the light and angle he uses will bring out their best qualities.

“They are so beautiful and so strong,” he says, charmingly speaking of his vegetable subjects as though they were people.

There is, in fact, a long tradition of treating vegetables like people in the photography world—and many a famous photographer has gone through a veggie phase. (Karl Blossfeldt and Edward Weston are well known for their still-lifes, but even Irving Penn, best known for his fashion photography, was into sexing up frozen vegetables.) Perhaps it’s because many vegetables really do have faces; look, for instance, at these potatoes, part of Andrezej Maciejewski’s series of Very Important Potatoes Portraits.

The same talented photographer currently has a show on right now at the Las Vegas Contemporary Arts Center. Maciejewski recreates paintings by the Old Masters as photos of fruit and vegetables—leaving their PLU tags on. The images are hung in the sort of opulent gilded frames one associates with classic still-lifes. It can take a few moments to realize what is off about his pictures.

Both of these exhibits can provide some inspiration as to how to better photograph a raw foodie’s kitchen (use natural light, take time with composition, turn off that godforsaken flash, try an interesting bowl or dramatic but simple dark backdrop, try recreating a classic image with produce). But what about the sad Instagram photos of meat, cooked food, and dairy?

For help in that arena, I called Susan Spungen, food stylist to the stars. She was the one who made food look yummy in Eat, Pray, Love and Julie and Julia. Before she got in the movie business, she had a long career making sure food looked perfect on the pages of Martha Stewart Living.

“Freshness is incredibly key,” she told me. “Our whole job is to keep the food looking fresh. If you are going to take a picture of your pizza do it right away... If you are going to photograph your steak, do it when it first comes out.” She reiterates what every photographer will tell you: “Push it into natural light,” adding, “Put it on a pretty plate that doesn’t have a pattern on it.”

If you follow these steps and are still left unsatisfied by your food photos, you may have been brainwashed by advertising food, which is about natural as the typical Victoria’s Secret model. Like those busty Angels, advertising food gets taped, propped, scrunched, tweezed, sprayed with shiny stuff, and enhanced with silicon parts.

In the editorial world, Spungen explains, there is a movement toward doing things more naturally. The idea is that you should be able to bite into what you see on the pages of a food magazine and find that it is, in fact, what the caption describes. Even so, for exacting photo editors, doing things naturally can mean “dumping out box of cereal—and telling the poor assistant to pick out the prettiest flakes,” then placing them in a sea of Crisco so that they sit just so, Spungen explains.

Certain things, like melty cheese and milk, are so unphotogenic that they usually require stand-ins or dozens of trials to get right. After so many years of using Elmer’s glue as milk, most Americans simply think that's what it looks like, Spungen says.

So don’t feel bad if your cereal looks like a bowl of maggots floating in a blue water. But maybe don’t post the pic on Instagram?

You can get more food insights from Spungen in the slideshow above.

Oh Snap! is Brow Beat’s weekly photo feature. Have you spotted a project that’s worth profiling? Pitch to ohsnapidea@gmail.com.