Watch TWO Tiny Comets Zip Past Earth This Week During a Very Close Encounter

On Monday and Tuesday, two comets will pass Earth in their orbits around the Sun. There are lots of cool things about this event: They are among the closest comets to have ever passed us in modern times, both are very small, one was thought to be an asteroid at first, but then it was discovered to be a comet … and it’s probably a chunk broken off the other one!

So there’s a lot going on here.

The two comets are 252P/LINEAR 12, and P/2016 BA14 (PanSTARRS). The comet 252P is the bigger piece, at roughly 230 meters across. Right away, that’s pretty small; the comet the Rosetta probe is orbiting right now (67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko) is 4 kilometers across, and most comets are bigger still.

But BA14, the second one, is even smaller that 252P. It was thought to be an asteroid when it was first seen in January 2016, but a deeper observation showed it to have a tail! That makes it a comet. The distinction isn’t really all that clean, but rules are rules.

I wrote all about these comets in February if you want details. In a nutshell, they have very similar orbits, and while it’s not 100 percent certain, it seems very likely they were once one object. Comets are somewhat fragile, being made of rock, gravel, and dust held together by ice. When a comet gets near the Sun the ice turns into a gas, and lots of the other material breaks loose. Sometimes a large chunk breaks off—we call that calving—and so BA14 having once been part of 252P is not without precedent.

The comet 252P passes us on Monday at a distance of about 5.2 million kilometers. BA14 passes Earth the next day at about 3.5 million kilometers. That makes them the fourth and seventh closest approaches by comets known, in fact. The animation below shows their orbits as they pass Earth. The Moon is about 380,000 kilometers from Earth, so they both miss us by about nine times that distance. As you can see, that’s a quite safe amount. There’s also a Java applet online where you can play with their orbits, too.

The paths of the comets as they pass Earth, centered on 252P/LINEAR. Animation by NASA/JPL-Caltech/Ron Baalke.

Still, even though it’s a close pass, neither will be terribly bright; in fact, BA14 will be invisible to the naked eye. Remember, they’re small. However, while I expected 252P to be very faint as well, it jumped hugely in brightness the past week and is actually a good binocular object; Universe Today has more on that (including a finder chart). It's not clear why 252P got so much brighter, but that generally happens in comets when a piece breaks off, or a pocket of ice suddenly turns to gas. That fits with the bigger picture of 252P calving to create BA14, too.

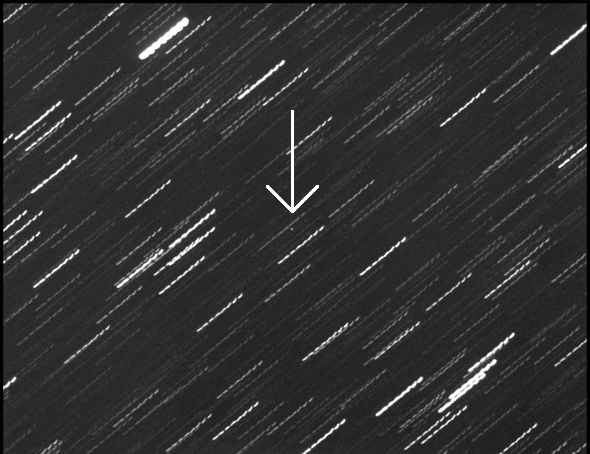

Record flyby comet P/2016 BA14 PanstarrsRecord flyby comet P/2016 BA14 Panstarrs: a stunning video by Gianluca Masi, The Virtual Telescope ProjectFull story here: http://bit.ly/1pqsNhZ

Posted by The Virtual Telescope Project on Monday, March 21, 2016

UPDATE, Mar. 21, 2016: Gianluca Masi of the Virtual Telescope Project (see paragraph below) has created this wonderful animation of BA14 moving across the sky from images taken just last night!

Even if you can't see them yourself from your location, the Virtual Telescope will be observing both worldlets, and you can watch live online Monday night and Tuesday night starting at 21:00 UTC (17:00 Eastern U.S. time). I’ll be tuning in to watch when I can. I’ve seen a lot of comets in my time—with my eyes, with binoculars, and with telescopes—and even though they’ll just be dots, the idea of seeing such a close encounter is compelling to me. I’ll note Hubble will be used to observe them as well, so I’m hoping those observations will be released as soon as possible (likely in a couple of weeks at least).

This event is a good reminder that there are a lot of objects out there. Many of them get close, and in many cases we don’t discover them until a few months out, or sometimes not even until after they pass us. The more we take these things seriously, the better.

Tip o’ the Whipple Shield to Ron Baalke at JPL for the animation.