Beyond Astronaut Ice Cream

How sci-fi writers like Arthur C. Clarke imagined we would feed space colonists.

Courtesy Philadelphia Inquirer via Matt Novak.

Read more from Slate’s special issue on the future of food.

When I was a little kid growing up in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I used to love visiting the Science Museum of Minnesota. The appeal was twofold: the gigantic triceratops and the astronaut ice cream.

Astronauts need near-perfect vision, and as a four-eyed kid, I probably wasn’t going to be launched into space. But at least I could eat like them.

There’s seemingly nothing that binds us more as a species—or more to our planet—than food. We build events and magazines and TV networks around it. We all gotta eat, and doing so can often feel like one of the most humanizing experiences at your disposal when you’re a few hundred miles from Earth. (Or so I imagine. I still haven’t been to space.)

Beyond the rocketry and such, food has presented one of the biggest challenges to human space exploration. Unlike robots, which don’t need to eat, drink, or even necessarily return to Earth, humans require fuel. And the prospect of space tourism—opening up new worlds even for those of us with myopia—makes figuring out how to feed ourselves in space even more important.

But the challenges presented by food aren’t only on the consumption end of things. Dr. Charles Bourland probably knows better than anyone just how difficult it is to make a palatable meal in space, having served as project leader of the NASA space food program from 1975-85. Now retired, I reached him at his home in Missouri.

I asked Dr. Bourland what the largest culinary change in the last 50 years of space travel has been. His answer: “the addition of the bathroom.”

“I’m sorry, the addition of what?” I said, not sure I heard him right.

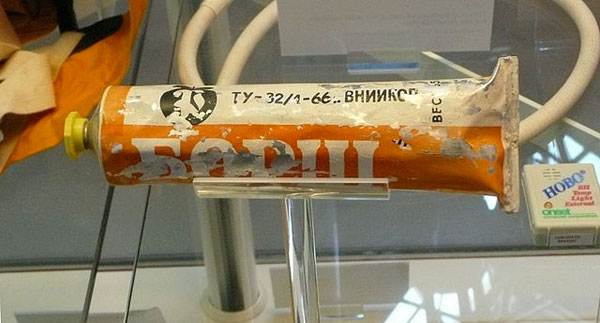

NASA.

“The bathroom. The astronauts in Apollo [in the 1960s] just didn’t eat because they didn’t want to go to the bathroom. … They were taking laxatives and enemas and everything else before the launch, and they didn’t eat. And when they got into space, they didn’t eat. You know, it’s like sitting in a Volkswagen with three people, and one of them is going to the bathroom. The odor lingers in there forever. The air filters take it out, but it takes a long time to take it out.”

When they did drink in space in the 1960s, it was water often flavored with Tang, of course. (But contrary to popular imagination, it was actually developed in 1957, prior to the U.S. space program.)

Once better toilets were installed in the 1970s, Bourland says, the astronauts “started eating. At the same time, we discovered that you could eat out of open containers in zero gravity without any problem whatsoever as long as the food was wet.” This gave the United States an unexpected edge in the space race. When a cosmonaut visited the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston in the mid-1980s, NASA served him a shuttle meal. According to Dr. Bourland, “He said, ‘That’s fine, but you can’t eat that out of an open container in space.’ I said, ‘Well, we did it all the time!’ ” USA! USA!

As Bourland breaks it down in The Astronaut’s Cookbook, which he co-authored with Gregory L. Vogt, you can divide space munchies into six different types:

- Rehydratable food: food that has had the water extracted on Earth, and added in space

- Thermostabilized food: heat-processed food that comes in cans or flexible pouches, similar to MREs

- Intermediate moisture foods: dried peaches, pears, beef—basically anything with 15 to 30 percent water

- Natural-form foods: nuts, granola bars, M&Ms, and other food ready to eat in flexible packages

- Irradiated meat: beefsteak, fajitas, breakfast sausage—meat that is cooked and sterilized by a radiation zap

- Condiments: ketchup, mustard, mayo, and hot sauce

That’s all well and good for the journey—in fact, it doesn’t sound too different from airplane meals. But should man colonize Mars, as SpaceX’s Elon Musk hopes to do by 2033, we’ll probably need to be able to grow food. Interestingly, many researchers see the developments of agriculture in space as part of a natural human progression into the unknown. A 2002 paper in the journal Advances in Space Research notes, “The process of adaptation to new environments will be no different than what farmers have done in the past as new environments on Earth were colonized.”

To cook up space food of the future, would-be explorers are of course cognizant of the space food of fiction. For decades, writers and artists have been dreaming up ways to feed those living full-time in space.

Curious children shuffling through libraries in the 1980s may have gotten their introduction to space food of the future from the 1982 book The Kids’ Whole Future Catalog: A Book About Your Future (underline in the original). It promised that things will be just a little bit shinier, just a little bit more amazing. Typical of its rosy futurism was an interview with a space farmer … of the year 2012!

Q: At lunch today, the waiter told us that all the food on the menu was produced here on Island One. Do you import any food from Earth?

A: No, it's too expensive. We raise every bit of food for all 10,000 of our citizens right here on this farm.

Q: You must have a very large area under cultivation?

A: Not really. We can grow all the food necessary to support one person in an area just 6 1/2 ft. long and 6 1/2 ft. wide. The entire farm takes up just 100 acres.

Q: How can you raise so much food in such a small space?

A: Well, for one thing, we raise most of our crops—hydroponically—in water instead of soil. That saves a lot of space because we can grow plants on tall vertical frames. Also, our farm produces food continuously—one crop after another, all year-round. It's always summer here, and we don't have any cloudy days or storms to contend with.

Q: Do you raise any animals?

A: Yes, they help us recycle leftovers. We raise our cows and goats almost entirely on corn stalks, cucumber vines and other crop wastes. Our chickens eat table scraps. Rabbits are our main sources of meat. They take up less space than hogs or cows and they need only half as much feed to produce a pound of meat. We also raise fish in those ponds over there.

Q: Where do you get the water for the fish ponds?

A: All the water in the colony is used over and over again. Water for drinking and cooking comes from the farm's dehumidifiers, which pull moisture out of the air. Waste water is purified in a solar furnace and then piped back to the farm.

Q: Have you had any crop failures?

A: Not so far. When we started the farm, we inspected the shipments of plants and seeds from Earth very carefully to make sure they didn't contain any weeds or insects. Now our farm is pretty much pest-free.

Q: Do you miss your farm back on Earth?

A: Not a bit! I've even learned to like rabbit burgers!

An article in the March/April 1988 issue of 21st Century magazine, which told the tale of a farmer on the moon in the on New Year’s Eve, 2019, takes a less optimistic view of the ease of raising animals in space. Authors Frank Salisbury and Bruce Bugbee imagine:

It’s time to go to the restaurant for the last lunar meal of 2019. The menu gives us choices for three days. We had to choose which day’s menu we wanted when we ordered breakfast, so that our diet is carefully balanced. The menus are impressive, considering that our colony is less than 10 years old and reached its originally assigned 100 occupants only about 5 years ago. Now, there are 250 people living here. We are all basically vegetarians, though not necessarily by choice!

Later, the article explains:

Growing food on the Moon is expensive for several reasons. For one thing, we can’t depend on light from the Sun as the source of energy for photosynthesis. The lunar night is nearly 15 Earth days long, and when the Sun shines it is difficult to use the sunlight directly to irradiate our crops. Even if an Earth-type greenhouse could be made leak proof, it could never contain an atmospheric pressure sufficient for both plants and the humans who take care of them.

NASA.

Arthur C. Clarke’s 1986 book July 20, 2019: Life in the 21st Century focuses on the same year as Salisbury and Bugbee’s piece. He predicts that food in space generally won’t be very palate-pleasing—not because the food is necessarily flavorless, but for a physiological reason.

Bonnie picked out several days of menus earlier in the week; now it’s easy to glide over to the galley and pull out the plastic tray. Back at her table, a place-setting is waiting for her, with magnets holding the silverware in place: a knife, fork, spoon, and pair of scissors. The scissors are for cutting open the ubiquitous plastic packs. In the middle of the table is a set of water nozzles resembling those used by dentists. She can reach for a nozzle on its hose, stick it into an opening in a plastic pack, then watch while the freeze-dried food soaks up the water. She has picked out a breakfast of thermostabilized peaches, freeze-dried scrambled eggs with sausage, rehydratable corn flakes with blueberries, and orange juice and coffee in plastic squeeze bottles.

The only trouble is that none of this is tasting very good. That isn’t because it has been dried and reconstituted; it’s because of the congestion in her sinuses. Weightlessness might fulfill the dream of effortless levitation and dreamlike flight, but it carries with it the continual feeling of a stuffed up nose.

This is a game we’re still playing. The May/June 2007 issue of Nutrition Today imagines what eating on Mars will one day look like:

Astronauts would require a balanced diet in both space and on the Martian surface and would need the energy and nutritional wherewithal to overcome the classic difficulties posed by the rigors of spaceflight especially loss of bone calcium and shielding from external radiation sources. In one scenario, nonmanned capsules would be launched to Mars in advance of astronaut liftoff to provide a “cache” of food and water for human use once the shuttle reached the planet. Proponents of the Manned Mars Mission state that once on the planet’s surface, fresh food could be available. They argue that it would be feasible to grow strawberries and raise rabbits and a host of other potential foods under controlled conditions.

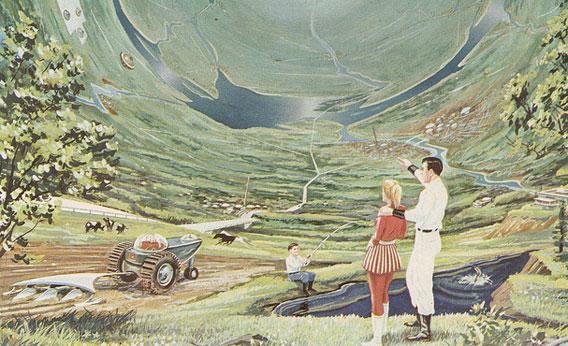

One thread that goes through most of these depictions of our space-food future: We want to create mini-Earths wherever we go. Perhaps the April 30, 1961, issue of the Philadelphia Inquirer shows this best. In a full-page article on “living in space,” a huge illustration shows a space colony inside of a hollowed-out asteroid. A tractor tills the soil. A boy catches a fish from a nearby pond. Three cows stand in the distance. Along the same lines, a scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 classic sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey shows three astronauts picking out sandwiches while commenting on how much better they taste than they once did. The simplicity of the sandwich let movie-goers place themselves in that scene—a sandwich, just like home.

Much as the 5-year-old in me still loves the idea of astronaut ice cream, there’s something tremendously comforting about the familiar terrestrial food of Earth. And one day, when I’m hopefully taking a short vacation on Mars, I suspect I’ll long for a sandwich. Just like Mom (or Mr. Kubrick) used to make.

Also in the special issue on food: five “food frontiers," including technologies to make diet food tastier and fight salmonella; small-scale farmers decide whether to embrace automated agricultural equipment; the United States and Europe switch perspectives on GMOs; celebrating the inevitable decline of the cookbook; and the case for bringing back home ec. This project arises from Future Tense, a joint partnership of Slate, the New America Foundation, and Arizona State University.