House of Pain

Obama may be president. Democrats may keep the Senate. But the House isn’t going anywhere.

Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images.

A few weeks ago in Charlotte, I sat down in the Huffington Post Oasis’ yoga studio and listened to Rep. Nancy Pelosi describe how she’d get her old job back. Democrats needed 25 seats to take back control of the House. “We’re going to get them,” she said.

With no PowerPoint, no chalkboard—not even a calculator—Pelosi proceeded to bring the math. “There are 63 seats which are held by Republicans which were won by President Obama,” she explained. “Of those 63 seats, 18 were also won by John Kerry. There are those who count that as 18 [for us]. We don’t. Give them six. We’ll take 12. Of the 45 remaining, give them 30. I think that’s generous. That’s the worst-case scenario. Fifteen plus 12, that’s 27.”

Could it be that simple? Almost. “There are districts where people are, shall we say, ethically challenged, and we believe we have excellent chances to win,” Pelosi said. What about her party? “We believe that any Democrats who could survive the year from hell have a good chance of winning again.” (She is referring to the “shellacking” of 2010.) And where would the new seats come from? “In California, New York, Illinois, and Texas, we have half of what we need.”

It was the best spin Democrats could come up with. Nobody in the room—reporters, bloggers, reporter-bloggers—looked terribly convinced. We were in North Carolina, where less than a mile away Republicans were mocking one of Pelosi’s “year from hell” survivors by renting an Uber car and daring Rep. Larry Kissell to ride it into Charlotte. If Democrats were so sure they’d win the House, well, what was Kissell waiting for?

Weeks later, ever since the Charlotte Democrats emptied their confetti cannons, the election’s been breaking their way. Barack Obama leads Mitt Romney outside the margin of error; swing-state polling has him winning around 330 electoral votes. For the first time all year, Obama’s party looks likely to keep control of the U.S. Senate.

But Democrats aren’t winning the House. The Cook Political Report, which meticulously tracks and rates House races, pegs the maximum Democratic gain at eight seats. At this point in 2010, it was predicting Republican gains in the high 40s, and the party wound up with 63 new seats. The Fix, Chris Cillizza’s election bible, gives Democrats the advantage in 182 seats and rates 27 more as “toss-ups.” If Democrats won them all, they’d still by eight seats short.

And any schmuck could have warned you years ago that this would happen. In 2010, Republicans predicted that a broad election win—one that gave them most state legislatures—would keep the House for a decade. “It could end up translating into control of 15 to 25 U.S. House seats for the next five cycles,” said Ed Gillespie, co-founder of the polling and strategy group Resurgent Republic and who spent endless hours counseling Republicans on the down-ballot challenge. (He’s now flacking his heart out for Romney.)

The Republican advantage was tremendous. Most states give the power of the map to whomever happens to run the legislature. As 2011 began, Democrats only controlled the redistricting process for 47 seats—safe blue turf like Maryland and Illinois, which they squeezed for every possible gain. They had to. Republicans controlled the process for 202 seats. The Democrats had built the Pelosi house in states like Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Then they lost everything, and the other guys got to draw the maps.

“Republicans weren’t thinking ‘Hey, just how do we draw these lines to screw over Democrats?’ ” says John McHenry, a pollster at Resurgent Republic. “It was, ‘How do we make this suburban Philadelphia seat safer for the Republican who just won it?’ The goal wasn’t so much to add seats as it was to hold on to the 2010 gains.”

Republicans and independent analysts figure that the new maps will save at least a dozen seats. In state after state, they followed the same pattern: Create more safe suburban districts and pack the Democrats into a couple of twisty gerrymanders. North Carolina, which narrowly voted for Obama in 2008, is now structured to elect Republicans in at least nine of 13 seats. (This explains that Uber for Kissell.)

But let’s focus on Ohio. Right now, Obama is winning the state, and Democrats are saying things like “it appears he’s going to run a little bit ahead in Ohio than he does nationally.” In 2008, Obama carried the state and boosted the whole Democratic ticket—10 of Ohio’s 18 members of Congress wore the blue jerseys. In 2010, Republicans snatched back five seats. The census took away two of Ohio’s districts, but Republicans redrew the map to make it functionally impossible for Democrats to win back turf.

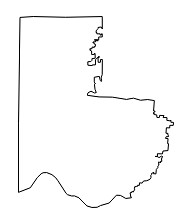

This (via the Cook Political Report) used to be Ohio’s 1st Congressional District:

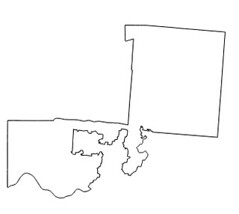

In 2008, Obama won this by 31,128 votes and swept Steve Chabot out of office. In 2010, Chabot won a comeback bid by 11,098 votes. The overall Chabot vote slipped from to 140,469 in 2008 to 103,770 in 2010. But he’s safe now. The new district looks like this:

The old district forced Chabot to compete in Cincinnati while winning Republicans in neighboring Butler County. But the new district excises Cincinnati—that’s the jagged hole—and brings in a chunk of Republican heaven, Warren County. It’s one of 11 districts that favor Republicans, and nine of them strongly favor Republicans. Obama may win the state with 51 percent of the vote while Democrats win 31 percent of the House seats.

Most of the GOP-run states now look like this. If you want a general idea of where blacks, Hispanics, and liberal whites don’t live, load a new district map of North Carolina or Pennsylvania or Michigan. If you’re worried about partisanship, it’s time to upgrade to panic. Anyone who wins a new, safe seat can safely ignore whichever kook or LaRouche cultist runs against him. He only has to worry about staying pure enough to win his primaries. In a long look at the new maps, Robert Draper talks to Rep. Blake Farenthold, who’d be a fluke one-termer if the Texas legislature didn’t shore up his seat. “This [new] district is a much stronger Republican district,” Farenthold says to Draper. “You say the same thing, but you use different words. Immigration would be an issue … you’ll be a little softer about how you talk about it in a swing district than in a harder-core Republican district.” Any Democrat in Ohio could say the same thing.

But from the Nancy Pelosi algebraic perspective, as pure politics, the new maps mean that it’s easier for a Democrat to win the White House than for his party to take the House. For generations, the exact opposite was true. The old New Deal coalition, from 1933 to 1995, gave Democrats control of the House for 56 of 62 years. The South would produce an army of Democrats—conservative, but good enough for the speakership—no matter who won the election. As late as 1984, Georgia voters could go to the polls, give Ronald Reagan a 20-point landslide, and give Democrats eight of their 10 congressional districts. “At the time,” former Reagan (and Nixon) strategist Roger Stone told me in an email, “we attributed our small gains to the districting maps—and, with party ID still near parity, the desire of voters for ‘balance.’ ”

Since then the Electoral College has shifted toward the Democrats. Obama has given up the old Democratic strongholds of the Deep South, trading them for the Hispanic-heavy Southwest, the Midwest, the Mid-Atlantic, and New England. The more diverse the state, the better the national Democrat does. Most of the country’s getting more diverse. It’s been decades since the GOP was able to compete for California or Illinois or New York, all of them won by Reagan and Nixon. It’s been 24 years since a Republican won Pennsylvania.

Maybe a swing state’s gotten impossibly tough for a Republican to carry. Carve it up right, and you can put the demographically troublesome voters in the districts where they can do the least damage to your party. “We'd have to see an amazing landslide in order for these districts to flip,” McHenry says. “If there was a big coattail effect, that would mean that the people who drew the districts didn't do very good jobs.”