20 Years in a Windowless Cell

Justice Kennedy finally figures out that solitary confinement is cruel and unusual.

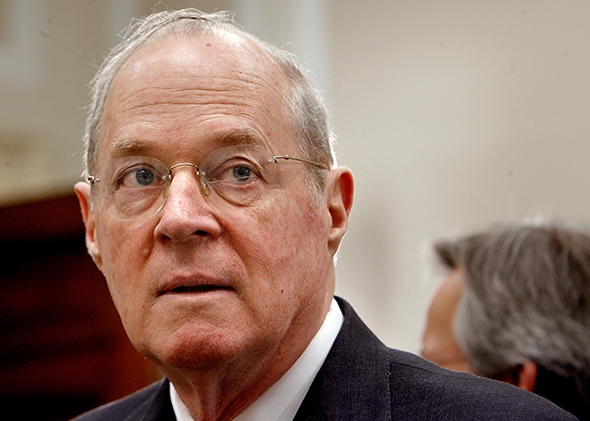

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

On Feb. 22, 1994, Justice Harry Blackmun handed down one of the most famous Supreme Court opinions of all time. Dissenting from the court’s decision to allow the execution of Bruce Edwin Callins, Blackmun graphically described Callins’ impending execution. The prisoner, Blackmun wrote, will “no longer be a defendant,” but “a man, strapped to a gurney, and seconds away from extinction.” Blackmun could not condone that fate. After years of struggling to enforce the death penalty fairly, Blackmun wrote, he was now convinced the entire system was unconstitutionally “cruel and unusual.”

“From this day forward,” he proclaimed, “I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death.”

On Thursday, Justice Anthony Kennedy channeled his inner Blackmun. Using a fairly obscure case as his vehicle, Kennedy drew a line in the sand, all but declaring his belief that solitary confinement is often unconstitutional. Kennedy’s concurrence lacks the rhetorical force of Blackmun’s renowned dissent. But it may wind up being even more consequential.

The case in question, Davis v. Ayala, actually has nothing to do with solitary confinement. Hector Ayala wasn’t asking to be released from his solitary cell; he was asking for a new trial, because his first one may have been tainted by unconstitutional race-based jury strikes. By a vote of 5 to 4—with Kennedy joining the rock-ribbed conservatives—the court rejected his request, holding that any racism at his trial was “harmless.”

But, as the Atlantic’s Matt Ford points out, Kennedy highlighted a disturbing detail in Ayala’s case at oral arguments.

“This doesn’t relate to the issues you’ve been arguing,” Kennedy said. “This crime was, what, 30 years ago—and the trial, 26 years ago? … Has [Ayala] spent time in solitary confinement, and if so, how much?”

“He has spent his entire time in what’s called administrative segregation,” Ayala’s attorney responded. “When I visit him, I visit him through glass and wire bars. … It is a single cell. … You are allowed one hour a day [outside the cell].”

The brief colloquy made a serious impression on Kennedy. In his concurrence, the justice wrote that if Ayala’s solitary confinement “follows the usual pattern,” he’s likely “been held for all or most of the past 20 years or more in a windowless cell no larger than a typical parking spot for 23 hours a day; and in the one hour when he leaves it, he likely is allowed little or no opportunity for conversation or interaction with anyone.”

Kennedy then described the “human toll wrought by extended terms of isolation,” the “terrible price” exacted by “years on end of near-total isolation,” including anxiety, self-mutilation, and suicide. Remarkably, to illustrate his point, Kennedy cites the recent death of Kalief Browder, who was charged with stealing a backpack at age 16, spent three years in solitary confinement, and hanged himself earlier this month.

Kennedy lauds “penalogical [sic] and psychology experts, including scholars in the legal academy,” for offering “essential information and analysis” about the horrors of solitary confinement. But oddly, he chastises the country for what he believes to be its apathy toward inmates. “[T]he condition in which prisoners are kept,” Kennedy writes, “simply has not been a matter of sufficient public inquiry or interest”:

Too often, discussion in the legal academy and among practitioners and policymakers concentrates simply on the adjudication of guilt or innocence. Too easily ignored is the question of what comes next. Prisoners are shut away—out of sight, out of mind. … [I]n decades past, the public may have assumed lawyers and judges were engaged in a careful assessment of correctional policies, while most lawyers and judges assumed these matters were for the policymakers and correctional experts.

This reprimand is myopic. Kennedy may have only just discovered the cruelty of solitary confinement, but civil liberties–minded individuals and advocacy groups have fought against the practice of decades. The American Civil Liberties Union routinely represents prisoners seeking an escape from solitary. NPR ran a groundbreaking series on the issue in 2006. States have been reforming their solitary confinement rules since at least 1998. The New Yorker’s account of Browder’s hellish three-year odyssey on Rikers, which Kennedy cites, may have drawn more widespread attention to the issue recently. But large chunks of the “legal academy” in the “public” were aware—and outraged—by the practice long before Kennedy condemned it.

Why did Kennedy choose this moment to convey his concerns about solitary confinement? From his concurrence alone, it’s pretty obvious that Kennedy followed the Browder tragedy. And Kennedy is famous for his visceral reactions to stark images of human cruelty—he famously attached photographs of an overcrowded prison in a decision forcing California to release or relocate inmates.

Perhaps Kennedy is also uncomfortable with America’s refusal to abide by the international community’s increasingly settled view that solitary confinement is, in many circumstances, a human rights violation. America stands alone in its zeal for the practice, placing far more prisoners in solitary confinement than any other Western country. The U.N. Committee Against Torture and the U.N. Human Rights Committee have recommended that the practice be curtailed or abolished. In 2011, the United Nations’ chief torture investigator recommended all U.N. member nations forbid virtually every use of solitary confinement.

Kennedy is both celebrated and reviled for including references to international law in his death penalty decisions. He once wrote that the court may take into account the “opinion of the world community” and “civilized nations” when determining which punishments are unconstitutionally “cruel and unusual.” No other “civilized nation” uses solitary confinement as widely as the United States. That fact may well have pushed the cosmopolitan Kennedy to invite a legal challenge to the practice.

As BuzzFeed’s Chris Geidner points out, Kennedy didn’t really need to telegraph his readiness to rule against solitary. In March, the 4th Circuit ruled that Virginia may automatically place death row inmates in solitary confinement. That case may well wind up before the Supreme Court next term—where, it now seems likely, five justices will be prepared to rule against Virginia. Striking down one state’s policy of automatic solitary confinement won’t dramatically curb the practice. But it will send a clear message that the court is finally ready to serve justice on this issue.