Voting Rights 2.0

Why we still need the Voting Rights Act, and how the Supreme Court could make it work better instead of striking it down.

Congressional District 23 cuts across a rural swath of southwestern Texas, from the state’s border with New Mexico, hundreds of miles south along the Rio Grande, stretching east to San Antonio. It’s among the least densely populated terrain in the country—and the most electorally disputed. The district was created in 1967, two years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The voters of District 23 sent a Democrat to Congress every term until the 1992 election. At that point, following the 1990 census, which gave Texas three additional seats, District 23 was redrawn to include a Republican-leaning part of San Antonio. Republican Henry Bonilla won the 1992 election. And in 2003, the district was redrawn again to keep him there, by moving 100,000 Latinos out.

Bonilla was still in office in 2006, when the Supreme Court ruled that District 23 violated the Voting Rights Act. The act bars states and cities from discriminating against minority voters with crude tools like poll taxes and literacy tests (and in our time, some voter ID requirements); it also aims to ensure that when district lines are redrawn, they can’t be gerrymandered in a way that dilutes the electoral power of minorities. District 23 was supposed to be a Hispanic opportunity district—one in which Latinos could potentially elect their preferred candidate despite the racially polarized voting patterns of Anglos in the area. From ’92 on, Latinos were voting against Bonilla in greater numbers each time, nearly ousting him in 2002. But the 2003 map, the Supreme Court said, in essence “took away the Latinos' opportunity because Latinos were about to exercise it.”

And so District 23 was redrawn once again, to add an infusion of Latinos and Democrats from another slice of San Antonio. In a runoff election with Bonilla in 2006, a Democrat named Ciro Rodriguez won. (He’d previously served in Congress until his nearby district was also redrawn.)

And then in 2008, the National Republican Congressional Committee targeted District 23 for the retaking. Two years later, the party politicians who controlled the state legislature and the latest round of redistricting after the 2010 census, effectively took Rodriguez’s seat away, handing it off to Republican Francisco Canseco—a Latino, but not the candidate most Latino voters supported. That, at least, is what was implied in a decision by three federal judges in Washington, D.C., who last August rejected the new map for District 23—along with the maps for the rest of the Texas congressional delegation, and the state Senate and House. (Two of the judges are Republican appointees. The third is an Obama pick.)

As the judges tell the story, the Republicans and their mapmakers tried for a particularly sophisticated circumvention of the Voting Rights Act in District 23. They didn’t reduce the percentage of Hispanic voters—they increased it, by 0.1 percent. But along the way, in the words of the court, the line-drawers “consciously replaced many of the district’s active Hispanic voters with low-turnout Hispanic voters in an effort to strengthen the voting power of CD 23’s Anglo citizens. In other words, they sought to reduce Hispanic voters’ ability to elect without making it look like anything in CD 23 had changed.” As proof, the judges pointed to an email from the lawyer for the Texas House speaker to one of the mapmakers, urging him “to help pull the districts’ Total Hispanic Pop and Hispanic CVAPs [citizen voting age population] up to majority status, but leave the Spanish Surname and [turnout numbers] the lowest.” This would be “especially valuable in shoring up Canseco,” the email continued.

The District 23 saga is a classic example of the partisan misbehavior that the Voting Rights Act, and in particular a part of the law called Section 5, was enacted to stop. The Voting Rights Act is often called the “crown jewel” of civil rights law. Section 5 in particular is also “powerful and intrusive” and “controversial,” in the words of Yale law professor Heather Gerken, because it gives the Justice Department the authority to block any change in the elections process—from the location of a polling place or the hours it is open up through redistricting—in the states that Congress chose to cover back in 1965. Based on patterns of voting discrimination at the time, the list of states and cities covered by Section 5 mostly lie in the South, along with scattered counties and cities elsewhere. When Congress last renewed the act, in 2006, it left the geography of Section 5 unchanged, after hearing testimony that racially polarized voting persists in the regions covered by Section 5 more than in the rest of the country.

At the end of this month, the Supreme Court will hear Shelby County v. Holder, a challenge to the continuing validity of Section 5, brought by the state of Alabama. It’s clear from a 2009 ruling by the justices that Section 5 is at risk. If it goes down, what will be lost—and what comes next?

A key question in Shelby County is whether it still makes sense to single out the South for special enforcement. There are arguments for keeping Section 5 as is, or tinkering with it, or scrapping it for something new, in this excellent debate forum run by law professor Richard L. Hasen (a frequent contributor to Slate). My own feeling about this question comes down to timing. While the South has come a long way from the racism of the ’60s, I don’t think it’s the Supreme Court’s job to take away a protection for minority voters Congress reaffirmed only six years ago. Section 5 isn’t perfect, and it doesn’t address many of the problems we have with voting in this country. But it’s one of the few tools we’ve got.

Talking to Nina Perales, the lawyer for the civil rights organization MALDEF, who told me the story of congressional District 23, I was reminded of Section 5’s traditional purpose and its ongoing significance. “It is critically important to us,” Perales said. “The essence of Section 5, the real heart, is that it prevents gamesmanship. Section 5 means when you remove one barrier, the jurisdiction can’t just come in with another one. From the Latino perspective, you see this particularly when a minority community is growing.”

Her point isn’t that without Section 5, the Latino voters of Texas would have no recourse. They’d still have Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which allows minorities to sue when a voting practice discriminates on the basis of race or ethnicity. This part of the law applies anywhere in the country. But it’s got fewer teeth than Section 5. The protections of Section 2 kick in only after lengthier litigation, usually giving an incumbent like Canseco another term in office to consolidate his power. Or, as Perales put it, “the first election after redistricting goes to the discriminators.” This time, however, new lines were drawn before the 2012 vote, and the candidate whom Latino voters preferred, a Democrat, won.*

Section 5 also gives the job of reviewing thousands of proposed changes, no matter how small-bore, to the Justice Department. “Section 5 is built especially for the stuff that’s under the radar,” Yale’s Gerken says. “The change to a school board election or a water district that no one would go to court over, because it’s too costly and slow.” When I asked my law student interns to look at the 15 objections the Obama Justice Department has raised to proposed changes in election practices in the South since 2010, they turned up big shifts, like statewide redistricting in Texas and voter ID in South Carolina—and also little stuff, like changes to the number of school board members in Pitt County, N.C., and the use of Google Translator, instead of live Spanish-speaking poll workers, in Gonzales County, Texas.

Gerrymandering in Georgia's State Senate

Georgia State Senate Districts as adopted

OK, so now you know why the loss of Section 5 matters. But there’s another chapter in the story of redistricting in the South, one that this term’s Supreme Court case doesn’t address directly, but that also matters enormously for who wins elections. In District 23, the problem was that, after the 2010 redistricting, there weren’t enough Latino voters who reliably turned out to elect the minority candidate of choice. But in states like South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Virginia, black legislators worry just as much about another kind of redistricting—the kind that packs more African-American voters than necessary into a relatively small number of districts, so that white voters more easily hold sway in the rest of the state. In voting rights lingo, the problem in Texas was “cracking,” and the problem in these other Southern states is “packing.” If Section 5 goes down, the practice of packing may never get the attention of the courts that it clearly should.

Packing is an old charge. When Republicans took control of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1994, the packing of minority voters into safe districts in the South (districts that were going Dem anyway) contributed to the shift. "The strategy and tactics were to break the back of the Democratic gerrymandering of 1980 and create fair and competitive districts," Benjamin Ginsberg, then chief counsel to the Republican National Committee, told the New York Times. "A good part of that was the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act." Black leaders tended to support the tactic—after all, it vaulted black politicians into power who otherwise struggled to get elected. "These new districts are beneficial because they've made the U.S. Congress look more like America," the Rev. Jesse Jackson said in the same Times article—which also noted that in the House, “members of the Congressional Black Caucus lost the chairmanships of three committees and 17 subcommittees as a result of the Republican takeover.”

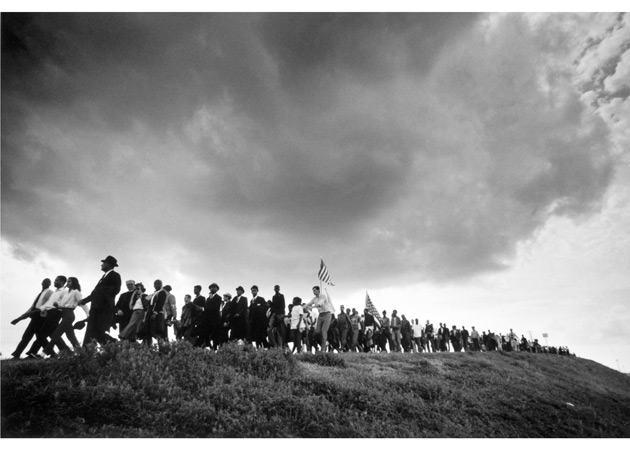

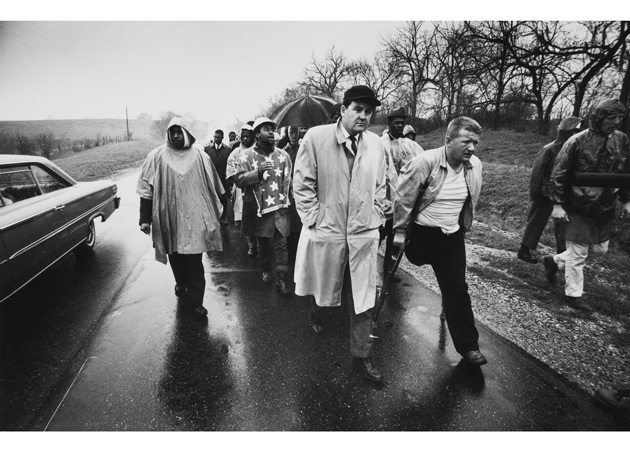

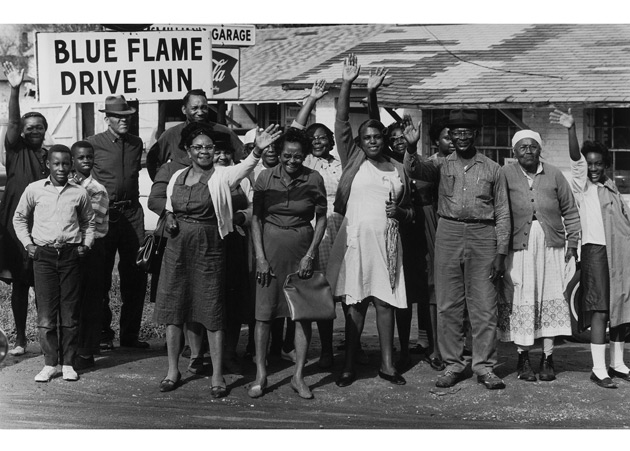

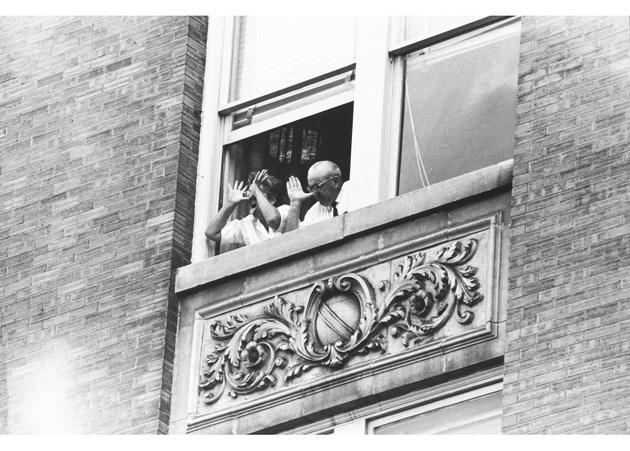

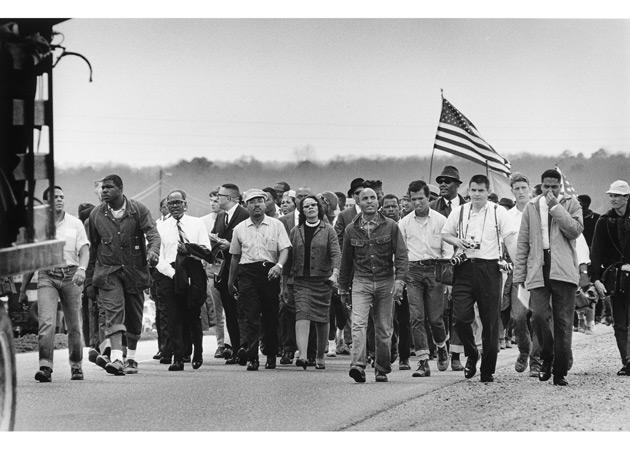

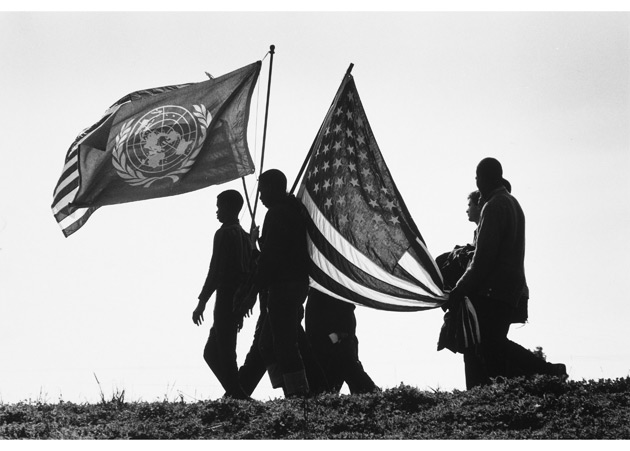

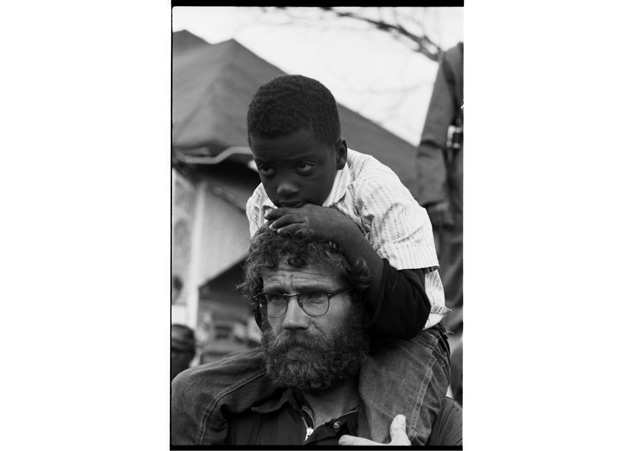

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Two decades later, many black politicians are speaking out strongly, in the press and in court, against packing black voters unnecessarily into safe districts—in essence, wasting their votes. The critics see an effort to take away the success African-American voters have had in building multiracial coalitions. They look at the map of the South and see some districts, particularly in urban areas, in which at least some white residents are willing to vote for black candidates. And they think black voters would be better off, in terms of getting the policies they favor passed, with fewer comfortably safe seats statewide, and more districts with a chance of electing their candidate of choice—who is almost always a Democrat. They want more crossover districts, as they’re called, in which black voters make up, say, 35 to 50 percent of the total, with white voters willing to make common cause, rather than districts with clear black majorities.

One of these black politicians is James Clyburn, longtime South Carolina congressman and assistant Democratic leader in the House. “Now we have one Democrat in Congress from Louisiana, who is a black person,” he pointed out to me. “We have one Democrat in Congress from Alabama, who is a black person. One Democrat from Mississippi and one from South Carolina, also black. This comes from stacking black people in one district rather than making other districts competitive.” Clyburn paused. “If you create districts that you know full well will Balkanize the voting process, you are undermining what democracy is all about.”

Another critic of packing is Stacey Abrams, the 39-year-old minority leader of the Georgia House. Abrams is super-smart and personable—I know her from law school, and I think she could be an African-American candidate with widespread appeal. To move up, she wants to show she can represent voters of different races. But after Georgia’s 2010 redistricting, Abrams’ district went from 55 percent white, in terms of voters who reliably turn out, to 39 percent white. “We’re trying to get to race neutral voting,” she told me. “We want communities to align on common interests, not based on the superficiality of race. And Georgia was doing that. We had five black-majority districts represented by white people, and three districts, including my own, in which white voters elected people of color.” But in redistricting, Abrams says, the Republican-controlled legislature “targeted white Democrats in a way that was just egregious. The point is to make us the black party. This is about playing on the subtle fear of race in the South, and sending a signal to whites—no one here looks like you, so no one will share your values.”

The other side of this coin is white Democrat Brad Miller, part of North Carolina’s congressional delegation from 2003 until last month, when his district, which had been 28 percent black, was “divided six ways,” he said. “The Republicans packed all of the Democrats they could into three districts. Two were majority-minority, with higher percentages of black than before, even though they had already elected the black candidates of choice easily. The reasonably competitive coalition districts, like mine, just went away.” With his old district in splinters, Miller left Congress.

Does Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act allow for packing? At the moment, it appears the answer is yes. Over objections about this practice by black lawmakers and in some cases the NAACP, the Justice Department has approved 2012 redistricting plans in South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana. (Virginia is having a huge fight over a GOP-drawn state Senate map that the NAACP says similarly dilutes minority voting power.)

Some critics of the redistricting think the Justice Department is sitting on its hands because of the pending Supreme Court case. When I called DoJ officials, they wouldn’t comment. But the law professors I talked to say DoJ doesn’t have a lot of leeway here. The Supreme Court has never required a state to create crossover districts under the Voting Rights Act, or prevented a state from converting its map from several crossover districts to a few packed ones. In Georgia v. Ashcroft, decided in 2003, the court said states could turn to crossover districts, instead of majority-minority districts, to give minority voters power. But six years later, in Bartlett v. Strickland, a Section 2 case, Justice Anthony Kennedy praised crossover districts in theory while making them harder to achieve in practice. “Crossover districts are, by definition, the result of white voters joining forces with minority voters to elect their preferred candidate. The Voting Rights Act was passed to foster this cooperation,” he Kennedy wrote. But then he expressed concern about fashioning the Voting Rights Act into a partisan tool wielded merely to elect Democrats. “The statute does not protect any possible opportunity or mechanism through which minority voters could work with other constituencies to elect their candidate of choice,” Kennedy said. Meaning, the Voting Rights Act is not meant to give minority voters an electoral advantage, just a fair playing field. In the end, the court’s Bartlett v. Strickland decision says that when it comes to redistricting, voting rights protections kick in only where minority voters make up more than 50 percent of the electorate. The upshot, so far, is that black and Hispanic voters in Southern states have the right to a certain number of majority-minority districts, but zero crossover districts.

Since Bartlett only dealt with Section 2, however, there remains an argument that unnecessary packing could violate Section 5—here’s a spirited rendition from Jason Carter, a Democrat in the Georgia State Senate and a lawyer. So far, this position hasn’t gotten traction in court. It’s easier for judges to see their way to striking down congressional District 23 in Texas than Stacey Abrams’ reconfigured district, which after all makes it easier for her to win reelection, even if it’s at the expense of white Democrats like Brad Miller and the broader interests of black voters. If Section 5 remains in force, however, and Southern legislatures increasingly cram minority voters into a small number of districts, courts will face growing pressure to address the problem. “This is an issue we’ve only been lucky enough to face in the last few years,” Loyola law professor Justin Levitt points out. “So it’s not surprising the courts haven’t caught up yet.”

Maybe there’s a better way to deal with gerrymandering, one that doesn’t rely on race at all. And maybe if Shelby County v. Holder brings Section 5 down, Congress will get its act together to pass national voting reform. But how likely is that? I heard many times while reporting this piece that, given that the Voting Rights Act is the law on the books, the courts should recognize both cracking and packing as potential violations, depending on the history of a particular state and the continuing degree of racially polarized voting, and other facts that courts are good at gathering. At first it seems confusing: It would be against the law to create a district that’s 55 percent African-American in one place and 40 percent in another place? But if actual voting patterns differ, maybe the federal standard should, too. If the goal is to make sure redistricting doesn’t take away the power of minorities at the polls, then that actually seems like the best way to reach it.

“In 1970, fewer than 1,500 blacks nationwide held elected office,” New York University law professor Richard Pildes has written. “By 1990, that number had increased to more than 7,300. No other civil rights statute can boast such demonstrable gains.” Race relations in America are ever dynamic and changing. And crossover districts represent a hope for the present and the future—a world in which fewer people vote based on skin color. The Voting Rights Act has helped bring us closer to that world. But if Section 5 goes down this spring, before its work is done, we may not get there.

Correction, Feb. 19, 2013: The original sentence stated that the redistricting lines in Texas were redrawn after a federal court ruling in Washington, D.C., last August. In fact, the new lines were set in March 2012 by another federal district court in Texas. (Return to the corrected sentence.)