Separate/Together

Do couples who share some but not all of their money have a lot of hassle or the perfect compromise?

This series is now available as an eBook for your Kindle. Download it today.

Before I started interviewing couples for my series on how long-term couples manage their finances, I assumed that my husband, Mike, and I would end up with a combination of joint and personal accounts—the Sometime Sharer method of financial organization. Then my interviews with Common Potters (couples who combine everything) made me see benefits I hadn't expected. And yet we both still cleave to the idea of keeping a share of financial privacy. I thought becoming Sometime Sharers would let us snuggle under a warm blanket of unity while breathing our own air. The best of both worlds, in my fond hopes. I found some research to back up my instincts. In a qualitative study of Swedish married couples, sociologists found that the way money was defined changed the way that money was used. "For women in particular," the researchers discovered, "having money defined as 'mine' versus 'ours' was an important source of economic independence."

Yet as I talked to married and cohabitating couples about their Sometime Sharer systems of joint and separate accounts, it all sounded pretty stressful. When a couple first decides to merge just a portion of their finances, they have to decide how to fund the joint account. How much money to put in? Do you contribute a percentage based on your comparative salaries, or do you each put in half of the pot? After that's figured out, then you have to discuss what constitutes a shared expense. For example, would the stylish new winter coat Mike just bought come out of our joint account? Or is he on his own, because his old winter coat is still perfectly serviceable? And what about the bodega coffee I buy every day on my way to work, in addition to the coffee we make at home? Does the shared fund bankroll it, or is my caffeine addiction my problem?

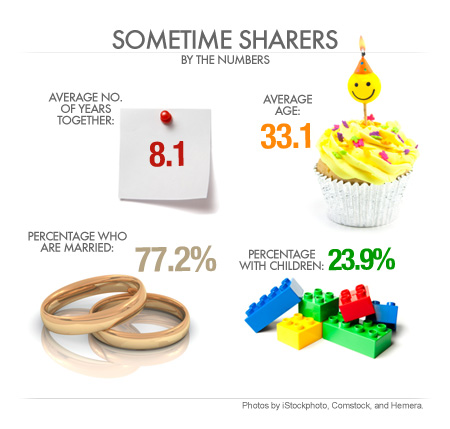

Answering these questions, I learned, takes a lot of initial wrangling. The combination of frank talk and hassle seems worth it for a good chunk of our peers, since the typical Sometime Sharer method couple is just like Mike and me. They have been together a good while (an average of eight years, compared with 11 years for Common Potters), but they don't have kids (24 percent compared with 46 percent). They're like Brendan and J.P., a gay couple living together in Los Angeles, who started dating in 2002 and are both 31. Both working lawyers, Brendan and J.P. didn't want to combine all their money. J.P. worries that a Common Pot would lead him to be controlling. ("I tend to be more dominant," he explains.) The couple hoped that going Sometime Sharer would allow them to keep closer track of their spending and stop them from fighting constantly about who was paying for what, as they'd been doing while keeping their money separate.

For advice on how to merge, J.P. and Brendan turned to the teachings of perky personal finance guru Suze Orman, who instructs all couples to put in "equal shares, not equal amounts." J.P. was working at a "mega law firm" and making much more than Brendan at the time, so he put much more into the joint account—about 66 percent to Brendan's 33 percent.

J.P. insisted that they go in 50/50 on the mortgage on their two-bedroom craftsman, which would give each of them an equal say about the house. "I did not want to 'own' more of the house than he did and have it be a power issue," J.P. explains. This choice is unusual; most of the Sometime Sharer couples I talked to pay for all joint expenses proportionally based on salary. In 2009, J.P. and Brendan took new law jobs. Both J.P.'s and Brendan's salaries decreased. So they refigured the percentages they were putting into the kitty. Now J.P. puts in about 60 percent to Brendan's 40 percent. And yet in spite of all the tinkering, they're still fighting over money. Recently, J.P. went to the ATM to get money to pay the couple's cleaning lady, an expense they had budgeted for—and overdrew the joint account, because they'd underestimated how much they needed to put in. In the end, they racked up almost a dozen bank charges before realizing they had a negative balance. J.P. blamed Brendan for using the account to pay for things like movie tickets and freaked out. This led to an overhaul of the budget and a new rule: Each must check with the other before withdrawing a large sum, say, $200 from the joint account. They also padded that account so they'd be less likely to overdraw it. Both men say that the restructuring helped but concede that their Sometime Sharer method is still a work in progress.

Though they say they are happy with their Sometime Sharer method, my own diagnosis is that J.P. and Brendan—like Mike and me—don't enjoy the mechanics much. J.P. says that Brendan gets "grumpy" whenever finances are discussed—he even got a little grumpy on the phone with me about some of J.P.'s comments about their shared account. "I hate talking about money," Brendan says, bluntly. And yet the Sometime Sharer method requires them to discuss expenses often. This is the central conundrum of this method: It seems slick and modern, but it mires you in minutia most couples would be better off glossing over.

For Brendan and J.P., who are well-compensated, childless lawyers, keeping such close tabs is not essential. But for couples with the same issue of different spending metabolisms but less of a budget margin, the Sometime Sharer method seemed a godsend: The more profligate spender could be kept in check. Most of his earnings would be communal, yet he would still have the release valve of his own cash. Take Deb and her husband, Brett, the married marketing specialist and forklift operator I mentioned earlier who have a daughter and another child on the way. When the pair first got together, they kept all the money separate and split every expense 50/50, but over time, that proved too great a hassle. Also, Brett had a difficult time budgeting on his own and tended to buy impulsively. So the couple created a system in which they hold most of their money jointly, but each gets an allowance. This way, Brett can spend some money on baseball games with his buddies, or lunch out during the week, and the couple can still keep a very close eye on their finances for the long haul. "We only have so much," Deb explains, "So we have to make our lives fit within that budget, not the other way around."

Would couples like J.P. and Brendan, who don't have to stick tightly to a budget, put up with the discord of all their Sometime Sharer money discussions if they could marry legally in their home state of California? Brendan says that if they could get married, he would consider merging more money, while J.P. isn't sure whether their money management system would change much. As it is, since they can't marry, they don't have the legal protections that married couples have, like equitable distribution of wealth upon divorce, if they combined all of their money and then broke up. (They also don't get most of the tax or insurance breaks that married couples get, as the New York Times pointed out in this thorough and depressing assessment of the lifetime cost of being a gay couple.)

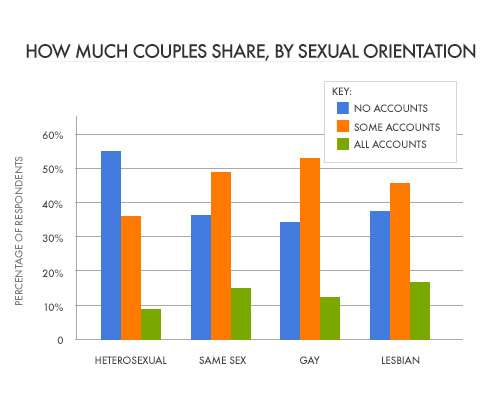

All of this may help explain why more than half of the unmarried gay men who took my survey had a Sometime Sharer system of shared and individual accounts, while 34 percent of them kept everything separate, and 18 percent had a Common Pot. By way of comparison, only 28 percent of straight unmarried people used a Sometime Sharer system, while a full 54 percent kept everything separate, and 18 percent used a Common Pot. Meanwhile, 37 percent of unwed lesbians used the Sometime Sharer method, with 37 percent keeping everything separate and 26 percent using a Common Pot.

Maybe gay couples are more likely than straight couples to pool some money when they're not married because for them, it's a stand-in for the marriage certificate they can't get in most states—a way to make a statement of togetherness and to feel emotionally married. J.P. and Brendan say that buying a house together was a game-changer that cemented their relationship, and they signed a contract saying they would both pay 50 percent of the mortgage. Swap house contract for marriage contract, and you'd have the more typical straight impetus for pooling funds. For Jack, 57, who has been with his partner Jim, 59, for 30 years (names changed by request), combining finances was "as symbolic a joining as the rings we gave one another on our fifth anniversary." (They live in Massachusetts and so did get to marry, finally, in 2004.)

Some unmarried straight couples use the Sometime Sharer method to signal the next step in a relationship, too. Sarah, 34, who has been with her boyfriend for more than seven years, says that he recently told her that he felt as if they weren't really partners unless they started a joint checking account. She was initially against it, but was convinced because, "He's not really a sentimental person," Sarah says, but he was "so sincere" about how the joint account would make him feel more like a real couple that she was moved. After Mike and I got married, I felt a bit like Sarah's boyfriend: Continuing to keep everything separate made our relationship feel slightly less substantial. I had promised to share my whole life with my husband, wearing a floofy white dress in front of 200 people—shouldn't some of our money be part of that bargain?

The How-To Part: Managing Sometime Sharer Accounts

When you decide to start merging accounts, you need to figure out what constitutes a shared expense. Brendan and J.P. created several categories of recurring expenses in an Excel sheet including groceries, restaurants, entertainment, utilities, and payment for their housekeeper (as noted above, their mortgage is a shared expense but divided differently). They track their money throughout the month using the personal finance Web site Yodlee.com.

One-off purchases are discussed on a case-by-case basis. For example, J.P. and Brendan decided that the plane tickets they purchased to visit Brendan's family for the Christmas holidays should be paid for out of the joint account. Another couple, Deb and Brett, recently decided that Deb's maternity clothes should come out of their joint account. "Brett told me to use the house account since it's not just frivolous clothes shopping. It's something that I needed because of a decision that we both made," Deb explains.

Like J.P. and Brendan, the majority of Sometime Sharer couples I spoke to deposited their salaries into individual accounts and then put a set amount into a joint account. But there were a few couples who did it the other way around: They funneled their salaries into joint accounts, then deposited a set amount into individual accounts as a sort of allowance. This is how Melanie, a 28-year-old administrative assistant, and David, also 28, who works at a nonprofit, handle their money.

Melanie's biweekly pay goes toward the couple's savings and to their separate allowances: 20 percent is Melanie's allowance, 20 percent is David's allowance, 20 percent is vacation savings, 20 percent emergency savings, and the last 20 percent is used for beer, wine, gifts to others, and meals out. She has set up an automatic deposit so that one-fifth of her salary goes into the separate accounts for each of these things. David's biweekly pay covers student loans, the mortgage, credit cards, groceries, and utilities. Melanie tried using Mint.com to keep track of their elaborate system but found that the personal-finance software wasn't accurately identifying the transfers between accounts. Now she just balances the checkbook twice a week online using her bank's Web site.

With this arrangement, David and Melanie have a lot of benefits of the Common Pot—feeling a sense of closeness and a shared financial mission—but without the one big drawback of feeling controlled. "It's given me personal freedom with my expenses while still being able to take care of my husband, our responsibilities to each other, and our home," Melanie says.

I like the rough outlines of David and Melanie's arrangement, but I confess to having Betty Draper-ish spasms when I start thinking about how intricate their grapevine of accounts seems. My first instinct is to tear up my plans of economic independence and just chuck all my money into a Common Pot for Mike to manage. My big strong husband is so much better at math, after all!

However, there's an obvious way to pare down this method that would give us the psychological closeness of a Common Pot, but still allow us our teaspoon of autonomy. Mike and I could deposit both of our salaries into one account and have allowances shoot off into individual pots. This is an extremely simplified variation of what Melanie and David do—and it's easy-peasy enough to save me from the fainting couch.