Bachelor of Design

The history, future, and proper appointments of the bachelor pad.

Courtesy of Warner Bros., TCM, and Twentieth Century Fox

In 1941, George Jean Nathan put out an essay collection titled The Bachelor Life. On the front of the dust jacket is a photo portrait of the author, who was a co-founder of the American Mercury, an editor of the Smart Set, and a drama critic remembered as the model for Addison DeWitt. On the rear is Nathan’s note to his publishers: “This will be set down by some persons, including the author, as a deplorably frivolous book.” The body of the text lives up to that hype. Nathan plays his prose zitherlike over the habits and habitats of the unmarried heterosexual male in a casually grand performance of urbanity, citing in passing that one party where Scott and Zelda set his sofa on fire, and so forth.

Turn to Page 15 of this deliciously insubstantial hymnal (Chapter I: “Mythology”; subchapter 3: ”Domicile”). Here we have a critical review of a cultural narrative now out of date but at that time up to the minute in its pulp romance of men living alone. Before the bachelor pad was the bachelor pad, it was practically a seraglio—“soft purple lamplight,” “tiger skins,” “ten-inch-thick Turkish rugs”—a vision Nathan knew was “fancifully romantic” and “aberrantly imaginative.” He tracked that lurid daydream back to Albany—the Piccadilly apartment complex called home by Byron, Raffles, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Ernest Worthing, and “a recognized variety of the ‘man about town.’ ” Nathan writes:

I have always been and am still baffled by the prevalent notion that the diggings in which a single man lives and has his existence are somehow rather mysterious and naughty …

I do not know the origin of the legend, [but] it is my guess that its source was in all probability the fashionable English polite comedy of the 1890’s. The celebrated Albany, in whose chambers the bachelor characters of Pinero, Jones, et al, titillated the fancies of the more proper theatregoing nobility and servant girls, doubtless first established the picture that still massages the popular imagination. … And thus it gradually came about, what with the large succession of Pinero and Jones imitators, that a bachelor apartment was permanently to be regarded as an amalgam of white slave den with everybody in evening clothes and a French boulevard farce with all the doors stuck.

That myth mutated after World War II, when America evolved new approaches to home life and and refabricated the frontier myth for Levittown, New York—and meanwhile, far away from suburban ranch houses, unmarried men were free on the range in the city. Commercial culture rose to the task of stoking their dread and of selling them all goods that promised to quell it.

Let us state the problem: It had long been a queer thing to be a bachelor. The unmarried adult male struck society as an oddity, something of an Other—and even the married man was not quite at home, at home, which conventional wisdom had always said was a feminine realm. “Home life as we understand it is no more natural to us than a cage is natural to a cockatoo,” George Bernard Shaw wrote in the preface to Getting Married. After the war, life became military-industrial modern, and lifestyle became a capitalist imperative. It was time for capitalist culture to produce an atomic-age paradigm of heterosexual male domesticity.

Courtesy of Universal Studios

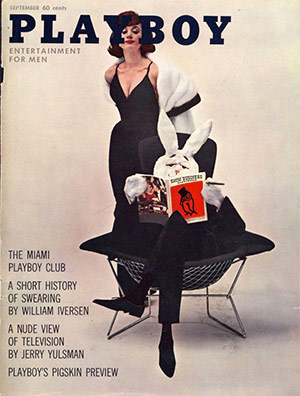

Thus, the bachelor pad—a midcentury institution and modernist trope, a machine for living large. The term has been horribly degraded over the years, so let’s be clear: A pigsty aspiring to the aesthetic of an unmopped sports bar does not qualify as a bachelor pad, nor do the vast majority of apartments inhabited by roommates, which lack the solitary bachelor’s freedom of environmental control. We’re talking about sophisticated digs, pretty toys, the sleek sovereign kingdoms depicted in Playboy’s design coverage of the 1950s and ’60s and in quite a few Hollywood films of the same era. Think of Frank Sinatra's floating clubhouse in Ocean’s 11, of Tony Curtis controlling traffic in Boeing Boeing, of Rock Hudson’s projections of traditional machismo in Pillow Talk.

In the inaugural issue of Playboy, December 1953, founder Hugh Hefner described his ideal reader—or, better, his ideal reader’s ideal fantasy self—as an indoor sportsman:

We like our apartment. We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.

Having a nice place was an existential necessity, he’s saying. This was plainly true of his magazine at the time, which thrived by mediating desire. Hefner’s cheerful attention to unpaid endorsements of furniture and electronics stoked readers’ lust for lifestyle coverage, which boosted circulation, which in turn made it rain with ad dollars. Hefner once called a September 1956 feature—“Playboy’s Penthouse Apartment”: “a hell of a place to live and to love and be merry”—“the most popular single feature ever to appear in these pages.”

Courtesy of Playboy

The scholarly literature on the bachelor pad is copious. Academics analyze Playboy’s design philosophy in terms of social history, sexual politics, and popular literature; everyone with an angle on performative constructions of gender has something to say. Studying a research file called “Architecture in Playboy, 1953-1979” [NSFW] was the most fun I’ve had with Princeton’s architecture department since the Beaux Arts Ball in ’95. And meanwhile across the golf course at the Institute for Advanced Study, Jessica Ellen Sewell goes for the gold:

The bachelor pad served as a way to think of an alternative masculinity, apart from work and family. In a 1958 essay in Esquire on “The Crisis of American Masculinity,” Arthur Schlesinger Jr. argued that men needed to “recover a sense of individual spontaneity. And to do this, a man must visualize himself as an individual apart from the group, whatever it is, which defines his values and commands his loyalty.” Visualizing themselves as bachelors, living lives of leisure, may have provided just such an opportunity for already-married men to recover their individuality, as well as to base that individuality on consumption. At the time these bachelor pads were articulated, bachelors were rare: in 1956, men’s median age at first marriage was at an all-time low of 22.5.

You’ve come a long way, bro. In 2014, Bloomberg News noted the passing of a demographic milestone: “Single Americans make up more than half of the adult population for the first time since the government began compiling such statistics in 1976.” So: Statistics show that America has an unprecedented supply of bachelors, and common sense tells us they’ve got to sleep somewhere, so let’s remodel our ideas about the bachelor pad. It will be good for single men to conduct their home lives with style. And clearly we must reject some obsolete elements of the pad ethos—for instance, the predatory technology of Pillow Talk, where Doris Day learns that Rock Hudson has a button that remotely bolts the door against her escape from his lair. But it will be good for the species for bachelors to cultivate an appreciation for the charm of a correct seduction and to rescue a few vintage mating rituals from the left swipe of history.

Thus, the Gentleman Scholar is proud to present a long list of stuff you can buy. It’s deplorably frivolous, I know—but some readers have big bonuses to spend, and others have to fantasize about squandering nest eggs, so let’s just get on with it. Uneasy about your complicity with late-stage capitalism? Ironize your dread by hanging a Barbara Kruger slogan ($9.50 for a package of eight “I shop therefore I am” postcards at CafePress) up on your fridge.

The Grand Scheme

The high point of Playboy’s design work was the Playboy Town House— “Posh Plans for Exciting Urban Living,” May 1962—designed by R. Donald Jaye and rendered by Humen Tan. It’s a masterpiece of fantasy real estate, painfully swank, and the closest reality has come to approaching it is at 101 East 63rd St. , between Park and Lex in Manhattan, in the 1990s and early 2000s. The owner was Gunter Sachs, the German-born heir to two industrial fortunes; the building, a 19th-century carriage house overhauled by the architect Paul Rudolph, most splendid ($38.5 million as listed by the Corcoran Group in 2012—not cheap, but it’s got a two-car garage).

Photo by Carter Hour/Flickr

I ought to be clear: “101” was not a bachelor pad in the truest sense. For instance, Sachs was not a bachelor and, on the contrary, bought this house while married to his third wife, Mirja Larsson, for whom he’d left his second, Brigitte Bardot. Also, Sachs owned 12 other residences, and this one might be accurately described as a pied-à-terre, or crash pad. But then again Sachs’ way of life—art parties, Gstaad hotties, maximized tax mitigation—all in all had a Superbachelor flavor.

Sachs’ house is a brilliant introduction to a proper high-modern concept of the bachelor pad, despite its unfortunate kitchen situation. (The downstairs kitchen was small and windowless, and the upstairs one was, too.) The space is at home with the vision of Le Corbusier, which is majestically detailed in the recent book Le Corbusier Le Grand ($200 from Phaidon). The spare air breathes the William Morris mantra: “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” The lesson to us all is: Simplify, simplify—and hang the walls with personally relevant pops of art.

The Living Room

When a bachelor invites a lady over, he should first hang her coat up on a hook ($199 for an Eames Hang-It-All at Herman Miller) and offer her water and a seat. The best kind of water is filtered New York City tap water served with ice ($22 for two Aalto glasses at the MoMA Store). The best kind of seats are those promoted by Playboy in the 1950s and 1960s.

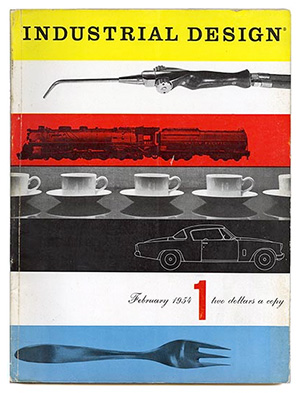

Courtesy of Industrial Design

At midcentury, Playboy was on the same page as Industrial Design and Architectural Record and everyone else, quite rightly, because the dominant style of the day had well deserved its ascent. Exhibit A: 1961’s “Designs for Living,” with its opening spread admiring the six new classicists: George Nelson, Edward Wormley, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames, and Jens Risom. This is what all furniture should be. This is what real furniture is. Everything else is either sentimental embellishment or just plain wrong.

A bachelor should go out and buy two new coffee table books—Mid-Century Modern Complete ($125 from Abrams) and The Art of Things: Product Design Since 1945 ($150 from Abbeville)—before committing to a coffee table. The practice of poring over these gorgeous volumes will perfect his eye—as will time spent with Dwell magazine’s Buyer’s Sourcebook ($13).

Or, also, here’s a fun exercise: The bachelor could turn his Pirelli calendar (unavailable for retail sale) to NSFW Ms. April (Candice Huffine as cruel as a lilac in a photo by Steven Meisel). Concentrate only on the Saarinen womb chair ($3,871 from Knoll) on which Huffine is perched. Empty your mind of everything but the chair. It’s important to like the chair. But for the right reasons! Don’t like the chair because it is a fashionable chair right now, much beloved by art directors responsible for wealth-management ads appearing in quality magazines. Like the chair because it is timeless.

But a bachelor shouldn’t overdo it—shouldn’t strike a strict midcentury tone in every corner of every room, shouldn’t furnish his home so it seems like the story of his life has been monotonously touch-typed in Helvetica. One way for a bachelor to mix up the frictionless modernism of the classic pad is to buy some pieces directly suggestive of work. Rizzoli Bookstore isn’t there any more on 57th Street in Manhattan, but better Brooklyn bookstores stock Rizzoli’s Vintage Industrial ($45). There, a bachelor will discover items rhyming with the high-modern classics, while also speaking to the contemporary inclination for the lumberjack-rugged and workshop-artisanal.

Courtesy of Best Made Company

Which reminds me: A thrifty bachelor will be best positioned to score deals at flea markets, antiques shops, and second-hand stores if he acquires a proper toolbox ($94 from Best Made Co.) and a clue of what to do with it ($35 for Reader’s Digest New Complete Do-It-Yourself Manual). Which reminds me: A resourceful bachelor is full of ideas for fun dates, such as a trip to the Cooper-Hewitt show on tools ($36 for two adults but pay what you wish on Saturdays from 6 to 9 p.m.).

The Stereo

Stereo tip No. 1: McIntosh makes a boss receiver ($6,500 for a MAC-6700).

Stereo tip No. 2: The average bachelor should not ask for stereo advice from guys who are really, really, really into stereos. Above a certain level, the world of the audiophile becomes an alien atmosphere—an ultraexpensive echo chamber of inaccessible acoustics. If you have to ask, you don’t want to know. Bang & Olufsen has probably got you covered.

Courtesy of McIntosh

Stereo tip No. 3: I suggest Stereolab—whose Emperor Tomato Ketchup ($18) earned an A minus from Robert Christgau—and not just because they once issued a collection of hypno-drone moog rock under the Esquivel-indebted title Space Age Bachelor Pad Music. Their noise buzzes the head, and the pulse of its groove will ease a segue to most any other make-out music, be it the grotty funk of Massive Attack or Portishead, or the synthetic sleaze of Peaches—or, this just in, new D’Angelo.

The Bar

The bachelor passionate about vintage cocktail books needs Playboy’s Host and Bar Book ($5 and up on eBay), which is a delight on every level. The author—Thomas Mario, a pseudonym—plays the host role with gusto, going on about “icemanship” in a fashion surpassing the wisdom of Kingsley Amis and sometimes very nearly the wit.

The bachelor passionate about cocktails themselves covets a few recent books. The Old-Fashioned ($19 from Ten Speed Press) is a handsome and compact production honoring the primordial booze of an essential drink; author Robert Simonson devotes one full paragraph to Ryan Gosling’s orange-twisting seduction technique in Crazy, Stupid, Love’s nightcap scene. Death & Co: Modern Classic Cocktails ($40 from Ten Speed Press) is an opulent production from an exemplary bar; try the Champs-Élysées on an enchanted evening. The Bar Book: Elements of Cocktail Technique ($30 from Chronicle) is a must-have guide to methodology; Jeffrey Morgenthaler empirically demonstrates that, squeezing a lemon, you get the most juice from a fridge-cold, nonrolled fruit.

The bibulous bachelor should be equipped to offer a guest a late-night drink, and he should heed Rosie Schaap’s first two rules of the honorable nightcap: “A nightcap should be a one-off, not ‘one more’ of whatever you’re drinking. ... A nightcap should also be brown.” And I have a modest suggestion—a rich elixir combining Cynar (pronounced CHEE-nar, a 33-proof amaro from Italy) and blackstrap rum (a traditional molasses-y menace to sailors on Saint Croix). I got the CynStrap recipe from its creator, Bryan Teoh: “It’s equal parts Cynar and Cruzan blackstrap rum. In a glass. No ice, no stirring, no shaking, no mucking about.”

The Kitchen

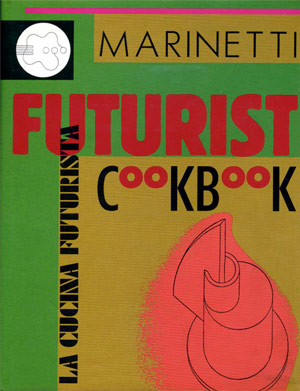

A crafty bachelor can survive on two books—Harold McGee’s On Food and Cooking and the Joy of Cooking—but other volumes have a place. Thus, here goes an aside directed to the holiday-shopping friends and lovers of kitchen-savvy bachelors: I Know How to Cook ($50) is a lovely vast volume—and if you make a gift of a copy to a friend, you should turn both its book ribbons to Page 394, “Cassoulet,” by way of dropping a hint. The book comes from Phaidon, the press behind Cookbook Book ($60), which beautifully reproduces pages from 125 sacred texts, cult classics, design triumphs, and/or oddities. But Cookbook Book has no ribbons at all, so also you should call Bonnie Slotnick to order a gift certificate and nonchalantly place that as a bookmark, perhaps at the sample of F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Cookbook, with the zabaglione in the sweet course of its “Declaration of Love Dinner.”

A bachelor desirous of a new cookbook but loath to lug another cyclopedic thousand-page behemoth into his home should ask Santa, baby, for a copy of Nigel Slater’s Eat: The Little Book of Fast Food ($28 from Ten Speed Press), which will sit in the palm of his hand singing, hearty and brisk. On Page 180 Slater shows us a sea bass with tarragon flageolets—and on the facing page he touts a downmarket version of that same meal: “a late-night sardine supper” of salt and pepper, oil and vinegar, canned fish and cannellini beans. “Hardly a gourmet feast,” Slater concedes, “but worth a thought when you’re hungry and perhaps a little the worse for wear.”

The Study

Courtesy of Taschen

Surely you’ve heard that a pipe sometimes is not just that: Hefner and his lapine mascot, puffing tobacco in a club chair or wherever, propped up a rich and powerful pretense. “The pipe marks its user as both contemplative and leisured,” Sewell writes. The Playboy philosopher had worldliness enough ($129 for a cork globe at CB2) and time ($85 for a vintage IBM clock on eBay) to muse upon “Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex”—a Maileresque catalog teetering between muscular intellectualism and farcical grandiosity.

Speaking of catalogs: A bachelor who appreciate art books in his den wants to be on the mailing list of Taschen, the Cologne, Germany-based publisher with high production standards, sumptuous conceptual ambitions, and good taste in lavish smut. Taschen just released a megadeluxe edition of Norman Mailer’s finest moment, his Esquire report from the 1960 Democratic Convention in Los Angeles, Superman Comes to the Supermarket ($150).

Speaking of New Journalism: A bachelor who likes to get his #longform on should lay eyes on the 50th-anniversary edition of The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge by Gay Talese ($35 from Bloomsbury). True, the prose romancing the workmen gets macho-sentimental, but it’s gusty up there, and Talese, so what’d you expect? Anyway, The Bridge is also packed with beautiful photos to appease bachelors without attention spans.

Speaking of Talese: Thy Neighbor’s Wife informs us that the seed money for Playboy—much of which went to purchase the famous Marilyn Monroe nudes—came from a $600 bank loan. Hefner, 27, used “as collateral the furniture in his Hyde Park apartment.”

Speaking of lavish smut: It is directly relevant to our theme to recommend two new books for your airy Ivar shelves ($53 and up at Ikea)—Polaroids ($65 for a lacy little project of the late Italian architect Carlo Mollino) and 1968: Radical Italian Design: Photographs by Maurizio Cattelan & Pieropaolo Ferrari ($80, includes the most provocative use of spaghetti in art since James Rosenquist’s “F-111”).

The Bathroom

A charged space for clear reasons: elimination and ablution, biology and psychology, disease and desire. Academic work on the bachelor pad tends to shy away from the subject, except sometimes to note that the Lascaux motif in the September 1956 Playboy Penthouse brings a shimmer of one traditional male space—the hunting lodge—to the fore.

Or maybe the academics are shying away because they have sardines on their breath. No one can tell for sure, but a bachelor should always keep an unopened toothbrush around in case a guest wants to refresh her dirty little mouth ($7 for a Binchoan-charcoal toothbrush by Morihata).

And while you’re at it, why not make the care of a warm smile the main theme of the master bathroom? The bachelor should develop an opinion on this lithograph of Mel Ramos’ Colgate nude (price on request from Galerie Fluegel-Roncak) and on a gouache-on-paper imitation of a 1947 Tek toothbrush illustration ($375 at George Glazer Gallery). He should compare the merits of the fluoridated pastiche of CSA Images ($42 at Art.com) with those of the eight heads of bristles on an 8 inch by 10 inch print from Etsy ($10).

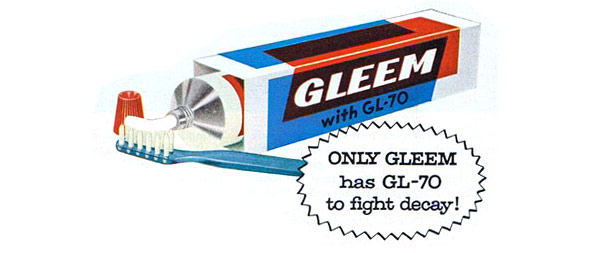

The scouring zing of baking-soda toothpaste is great, but five out of five art-school sweethearts prefer Donald Deskey’s deathless package design for Gleem.

The Bedroom

In the course of dissertating on Robert Rauschenberg, an art historian once write, “The bedroom served as the playboy’s most revered performance space.” But, here, Playboy falters at the threshold, tellingly. The Playboy Penthouse detailed in 1956 featured a horribly gaudy bed tricked out with a fridge, a dictating machine, a switch panel for controlling all the latest modern conveniences. A Northwestern Ph.D. dissertation on mass media describes that bed’s wires as the prosthetic tentacles of the techno-epicure:

Much as the apartment itself did on a larger scale, the penthouse’s bed enabled the bachelor to combine work and play, productivity and hedonism, and technological and sexual conquest. Without leaving bed—without even rising from a horizontal position for that matter—the inhabitant of Playboy’s fantasy bachelor pad could close the drapes, crank up the hi-fi, silence his telephone, and set the dishwasher to clean the lipstick stains off of the wine glasses from the previous evening’s dalliances.

That bed was made by—that mattress pad was contoured to fit—Hugh Hefner, whose personal habits are notably weird. In the 1950s, Playboy’s founder conducted many of his extramarital affairs in a bed chamber steps away from his office desk. In the 1960s, cutting back on deskwork, he began conducting his business affairs from bed, managing an empire in his pajamas. He was like Proust but with a Telex and photo selects and Dexedrine. This is not to mention the creepy-swinger vibes and literal vibrations of his and the magazine’s circular beds—beds as round as the O in so fucking tacky.

Courtesy of Design Within Reach

It is better to return to a bedroom humming a tonic note of tranquility. What do you need in there, really? Need is a strong word, remember. You need a bedside bottle of water ($8 for an Ikea Kullar thermos) and an AM/FM clock radio ($200 for a Tivoli Audio SongBook) and maybe a ceiling lamp ($210 and up at the Noguchi Museum) on a rotary dimmer switch ($5 and up at Home Depot). You need a bed, a bed superior to Hefner’s, and you ought to think on how to get it while honoring the austere Bauhaus bunk.

The most attractive bed at Design Within Reach right now is the Parallel ($3,150-$7,350, depending on whether you want a California king, a wide king, a king, a queen, a full; whether you’d rather have leather than fabric, walnut than oak; whether you imagine yourself at the decisive moment gliding a hand to an attached table to unfold a Trojan from its box). But you know what? Any minimalist arrangement spiffier than a box spring on a bare floor is perfectly fine. A bed is just a bed because this is your home—happy low, lie down!—your castle, your crown, your head on a queen-sized feather pillow ($99 from Tempur-Pedic). Good night, and good luck.

Disclosure: Slate is an Amazon affiliate; when you click on an Amazon link from Slate, the magazine gets a cut of the proceeds from what you buy.

Bibliography: A Selective Review of Critical Literature

Chudacoff, Howard P. The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Cohan, Steven. “So Functional for its Purposes: Rock Hudson’s Bachelor Apartment in Pillow Talk.” Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, edited by Joel Sanders, 28–41. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Dawson, Bret Maxwell. TV Repair: New Media “Solutions” to Old Media Problems. ProQuest, 2008.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. The Hearts of Men: American Dreams and the Flight From Commitment. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1983.

Fraterrigo, Elizabeth. Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Gwynne, Joel and Nadine Muller, eds. “Mancaves and Cushions: Marking Masculine and Feminine Domestic Space in Postfeminist Romantic Comedy.” Postfeminism and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Hollows, Joanne. “The Bachelor Dinner: Masculinity, Class and Cooking in Playboy, 1953-1961.” Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, Vol. 16, Issue 2, pp. 143-155. 2010.

Horton, Andrew, and Joanna E. Rapf, eds. A Companion to Film Comedy. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Nathan, George Jean. The Bachelor Life. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1941.

Ogersby, Bill. “The Bachelor Pad as Cultural Icon: Masculinity, Consumption and Interior Design in American Men’s Magazines 1930-1965.” Journal of Design History, Vol. 18, No. 1., pp. 99–113.

Pitzulo, Carrie. Bachelors and Bunnies: “Playboy” Magazine and Modern Heterosexuality, 1953-1973. ProQuest, 2008.

Poor, Natasha. Dirty Art: Reconsidering the Work of Robert Rauschenberg, Bruce Conner, Jay Defeo, and Edward Kienholz. ProQuest, 2008.

Preciado, Beatriz. Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy's Architecture and Biopolitics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2014.

Robertson Wojcik, Pamela. The Apartment Plot: Urban Living in American Film and Popular Culture, 1945-1975. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2010.

Schlesinger, Arthur Jr. “The Crisis of American Masculinity.” Esquire, November 1958.

Sewell, Jessica E. “Unpacking the Bachelor Pad.” The Institute Letter, (Spring 2012): 5.

Sorensen, Deborah. “Bachelor Modern: Mid-Century Style in American Film” in Blueprints Spring/Summer 2008, Vol. 26, No. 2/3. 2008.

Swiencicki, Mark A. Consuming Brotherhood: Men’s Culture, Style and Recreation as Consumer Culture, 1880-1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Filmography: A Cinematic Selection of Domiciles

The Moon Is Blue (1953) Directed by Otto Preminger; starring William Holden, David Niven; Otto Preminger films/Motion Picture Center studios

The Tender Trap (1955) Directed by Charles Walters; starring Frank Sinatra, Debbie Reynolds; MGM

Pillow Talk (1959) Directed by Michael Gordon; starring Rock Hudson, Doris Day; Arwin Productions/ Universal

Ocean’s Eleven (1960) Directed by Lewis Milestone; starring Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin; Dorchester/Warner Bros

All in a Night’s Work (1961) Directed by Joseph Anthony; starring Dean Martin, Shirley Maclaine; Hal Wallis/Paramount

Bachelor in Paradise (1961) Directed by Jack Arnold; starring Bob Hope, Lana Turner; MGM

Lover Come Back (1961) Directed by Delbert Mann; starring Rock Hudson, Doris Day; Universal/7 Pictures/Arwin/Nob Hill

Boys’ Night Out (1962) Directed by Michael Gordon; starring Kim Novak, James Garner; Joseph E. Levine/Kimco-Filmways/MGM

Come Blow Your Horn (1963) Directed by Bud Yorkin; starring Frank Sinatra, Lee J. Cobb; Essex/Paramount/Tandem

Sunday in New York (1963) Directed by Peter Tewksbury; starring Rod Taylor, Jane Fonda; MGM/Seven Arts

Boeing Boeing (1965) Directed by John Rich; starring Tony Curtis, Jerry Lewis; Hal Wallis Productions

The Silencers (1966) Directed by Phil Karlson; starring Dean Martin, Stella Stevens; Columbia/Meadway-Claude

The Pad and How to Use It (1966) Directed by Brian G. Hutton; starring Brian Bedford, Julie Sommars; Ross Hunter/Universal

Seconds (1966) Directed by John Frankenheimer; starring Rock Hudson, Salome Jens; Joel Productions/ John Frankenheimer/Gibraltar

In Like Flint (1967) Directed by Gordon Douglas; starring James Coburn, Lee J. Cobb; Twentieth Century Fox

There’s a Girl in My Soup (1970) Directed by Roy Boulting; starring Peter Sellers, Goldie Hawn; Charter Film Productions/Ascot/Frankovich

Down With Love (2003) Directed by Peyton Reed; starring Ewan McGregor, Renée Zelleger; Fox 2000/Twentieth Century Fox