Does This Rabbit Taste Like Tires?

Road kill: It's what's for dinner.

It really was a good-looking rabbit. Shiny coat, sleek body, glassy eyes—only its mangled back leg hinted at its violent cause of death. My husband Peter and I had come across this rabbit on a trip to a bird sanctuary in Gridley, Calif. It was lying in the middle of a narrow country road, stretched stiffly across the pavement; Peter swerved slightly to avoid its body.

"That was a pretty rabbit," he said, guiding the car back into the correct lane.

I agreed. We continued down the road in silence. Then, several hundred meters later, Peter spoke again.

"Should we go back and pick it up?"

He was suggesting that we take the rabbit home and eat it. Yes, I'm aware that this sounds crazy. And no, I'm not a back-to-the-land hippie: I grew up in Manhattan, where eating something off the street will likely result in an untimely death. But we were living in Oakland, Calif., dangerously close to Berkeley—the epicenter of the organic food movement, where the words local and sustainable are prized more than Michelin stars. This rabbit was wild, grass-fed, and presumably antibiotic- and artificial hormone-free. Except for the car that had hit it, no food miles had been accrued delivering it to us. So why not bring it home for dinner?

"I don't know," I said hesitantly, aware that now that the idea had been planted in our minds, we were going to have to do it. "Leaving it there does seem like a waste."

Peter made a U-turn. When we reached the rabbit, still lying sprawled across the pavement, I refused to get out of the car. Instead, I watched as Peter crouched down to examine the bunny and, with me telling him to only pick it up if it "seemed fresh," returned holding its stiff body in his hands.

"Only its back leg is messed up," he said as I stared into the rabbit's vacant eyes.

"Is it warm?"

"Sort of," he said, side-stepping the question. "Look at how nice its fur is. I could make a pouch."

Peter and I have different recollections of who was responsible for what happened next. But the end result was indisputable: By the time we pulled away, the rabbit was in our trunk, its plastic-bagged corpse right next to my yoga mat.

While official statistics are difficult to come by, a 2008 report by the Federal Highway Administration estimated that there are between 1 million and 2 million collisions between vehicles and large animals in the United States each year (rabbits presumably excluded). Large animals are usually called in to the authorities and hauled away, but small game is often not reported and therefore stays where it lands, pummeled by passing traffic until it blends into the pavement. Occasionally, a dead animal will be tossed to the side of the road, where it's picked on by birds and insects until only the bones remain. Only rarely does a human treat it as food—mostly because it's considered gross, but also because doing so is often illegal: Kirsten Macintyre, communications manager at the California Department of Fish and Game, later told me that under California law, "a car is not a legal method of take." (She then asked if I had heard the story about a guy in Pennsylvania who was arrested for trying to resuscitate a possum on the side of a road. The department is not without a sense of humor.)

Legality, however, was the last thing in our minds as we headed back toward Oakland. We had a much more pressing problem: what to do with the body. Neither of us had any idea how to skin or gut a rabbit, let alone determine whether its meat was safe to eat.

After stopping at a gas station to buy a bag of ice, I spent the next hour doing rabbit-related Google searches on Peter's BlackBerry. Among the things I learned: There are a lot of road-kill jokes on the Internet, none of which are useful when you are driving 60 miles an hour toward home with a mangled rabbit in your trunk. And if you do pick up a dead rabbit, you need to watch out for tularemia. Sometimes known as rabbit fever, it's a bacterial infection—catchable by inhalation—that's so toxic that it's actually been developed as a biological weapon.

This was not comforting. I needed to speak to an expert about whether our rabbit might kill us. Luckily, just as living in the Bay Area made it more likely for me to contemplate picking up the rabbit to begin with, it also meant that I actually knew people who might have an opinion on such things. I placed some calls and soon was on the phone with a friend of mine who raises rabbits for meat and tans their skins in an abandoned lot next to her apartment.

"The most important thing is to bleed it," she said, assuring me that our rabbit's healthy appearance made it unlikely that it carried tularemia.

When I told her that our rabbit was too stiff to bleed, she seemed unfazed. "Well, that's OK," she said. "Just brine the meat for a day in a 10 percent salt solution. You should be fine."

I wasn't entirely convinced, but we were now only 20 minutes from home, on an interstate surrounded by suburbs and strip malls. There was no turning back.

This might have been our debut experiment with road kill, but we were far from the first people to eat it—or to question why doing so should be illegal. In 1999, for example, Tennessee state Sen. Tim Burchett proposed a bill stating that "wild animals accidentally killed by a motor vehicle may be possessed by any person for personal use and consumption." The legislation eventually passed, but not before Tennessee was mocked in the press for what became known as the "road kill bill" and Burchett received a bumper sticker in the mail that said, "Cat—The Other White Meat."

Or take Alaska: For years, the state has allowed organizations to salvage meat from moose killed by cars, which they distribute to local charities. In December 2009 the municipality of Anchorage provided the Alaska Moose Federation—a volunteer organization that delivers moose to such recipients—with four trucks outfitted with 10,000-pound winches so that moose would no longer need to be butchered on the side of the road.

When it comes to road-kill-eating individuals, however, my favorite example is an Englishman named Arthur Boyt, who lives in West Cornwall with his wife, a vegetarian. The 70-year-old retired entomologist and competitive orienteer ate his first piece of road kill—a pheasant—when he was 15 years old, and hasn't looked back.

"I haven't bought a piece of meat since about 1976," he told me. "Maybe a sausage or two to bring to a barbecue, but nothing to eat at home." Boyt estimates that over the course of his 55-year road-kill-eating career, he's consumed about 5,000 animals he's found on the side of the road.

At first, Boyt only ate animals you'd find on a restaurant menu—pheasants, rabbits, hares. But eventually he moved on to more adventurous game. Today, he has a stand-alone freezer packed with pieces of animals he's collected over the years: badger, otter, roe deer, pheasant, partridge, pigeon, rabbit, and even a little bit of cat. "I've eaten three dogs," he told me matter-of-factly, emphasizing that he never kills animals himself. "Two greyhound mixes, and one Labrador retriever. Dog is one of the nicest-tasting meats I've ever had."

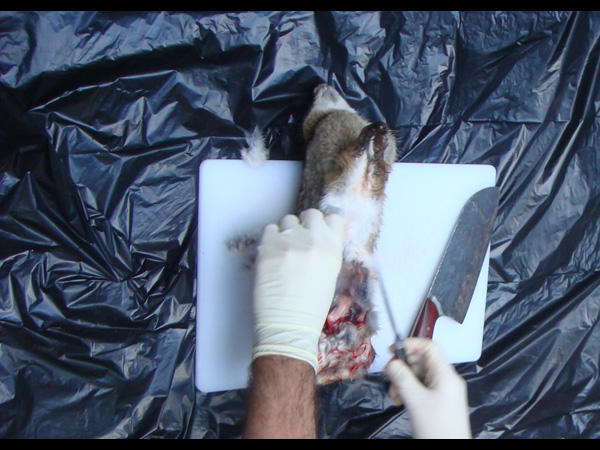

In comparison, I suppose our rabbit might seem tame. It certainly didn't feel that way, though, when we carried it out of the trunk, laid it on our kitchen counter, and contemplated the butchering ahead. As Peter watched instructional videos online, I prepared a Dexter-esque setup outside our kitchen door: plastic garbage bags spread across the concrete, two sets of plastic gloves, and a double garbage bag to receive the offal.

Then, with me acting as a surgeon's assistant, Peter began the procedure he had learned online. First, he pressed the rabbit's stomach to extract the urine. Next, he cut into its furry belly, slitting open its abdomen while being sure not to rupture its guts. It was a grisly scene, the rabbit's moist organs glistening as Peter slid them into the trash. But that was nothing compared to skinning. Several of the YouTube videos had related this process to "pulling off a sweater," and the comparison was apt: When Peter pulled its skin up over its head, the rabbit looked like a kid who'd gotten his shirt caught around his neck. Then, with several thwacks of the cleaver, Peter finished the job. He chopped off its head, removed its feet, and moved on to what I considered the worst step: cutting off its tail.

It was gruesome. The crunching of bone, the ripping of fur—these are not sounds that I like to associate with dinner. The irony, of course, was that this rabbit likely had a happier life—and a less painful death—than many of the animals whose meat I think nothing of buying from the grocery store. The key difference was that I was involved in the process.

But when you're standing in your yard with a garbage bag that contains a decapitated head, the mind has little room for reflection. Besides, with its skin, head, tail, and feet removed, the rabbit looked less like a childhood pet than it did a supermarket chicken. After discarding its smooshed back legs, we placed the rabbit's loins and forelegs in a salt bath, stuck it in the fridge, and commenced a cleanup effort that would make a serial killer proud.

The following day, we prepared the meat according to a recipe I helped write for The Big Sur Bakery Cookbook (though I never anticipated this particular use): wrapped in prosciutto, sautéed in white wine and butter, and garnished with a sprig of rosemary. We even invited a friend to join us. (I warned her of the menu ahead of time.) Peter arranged the legs on a serving plate and cut the loin into artistic coins as I cracked open a bottle of wine.

Objectively, the rabbit tasted fine—if a bit salty—and I ate the loin without too much trouble. (The legs were a bit stringy.) It was good to deal firsthand with the realities of where meat comes from. And I suppose a true Alice Waters devotee could argue that road kill is just country-speak for "foraged." But I'm not sure I would do this again. The next time I come across an animal on the side of the road, I'm going to keep in mind a point our friend made when we described how much of the rabbit had ended up in the trash: that when it comes to eating road kill, vultures are much more efficient.

Click to view Road Kill Slide Show: Not for the Faint of Heart.

Like Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.