Treacherous Element

The most beautiful, practical, and poisonous uses of lead in history.

Painting by Gion Seitoku/Image courtesy Brooklyn Museum

In a criminal lineup of the world’s metals, lead would be the dull, inoffensive-looking suspect. Next to the quicksilver fluidity of mercury, it is gray, solid, and dense. Judged against rigid iron, it melts and bends easily. Compared with the homicidal efficiency of white arsenic, it takes spoonfuls of black lead powder to off a victim—who would definitely notice the sweet taste.

So why is humble lead even a criminal suspect, especially when it’s done everything we’ve asked? For the past 6,000 years, lead has been vital to civilization—from lead pipes that brought clean water to thousands in Rome to lead batteries that power millions of cars. In 2014 alone, we used 11.3 million tons worldwide—about 3.4 pounds for each person on the planet.

To better understand our fraught relationship with this useful but poisonous element, we look back at 15 intriguing, surprising, and even horrifying moments from our long history with lead.

-

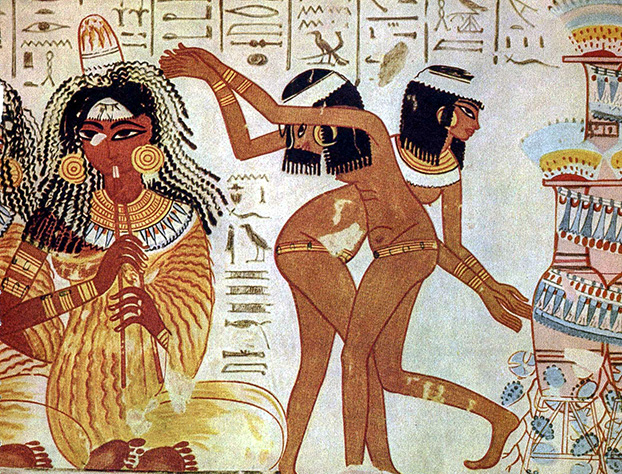

Egyptian fresco of kohl-wearing musicians and dancers from the tomb of Nebamun, 1350 B.C.

Abundant and found close to the Earth’s surface, lead was naturally one of the first metals to be mined by humans. Ancient civilizations regarded lead as more than a useful metal: Chinese sources recommend brewing elixirs with lots of lead, while Ayurvedic texts in India recommend preparing drugs with the metal. The Egyptian medical treatise, the Ebers Papyrus, even calls for powdered lead to treat eye problems.

Because of lead’s supposed medical properties—and the nice black powder it makes—it was a key part of ancient Egyptian kohl makeup. Even today, kohl often contains lead—which is why the Food and Drug Administration warns consumers against using this ancient cosmetic. “If something can get into the eye,” says toxicologist and epidemiologist Ellen Silbergeld of Johns Hopkins University, “it can get into the body.” And despite what the ancients believed, that is not a good thing.

CREDIT: British Museum

-

Bronze ding vessel from the Shang Dynasty, 10th–11th centuries B.C.

Ancient Chinese metalworkers alloyed bronze out of copper, tin, and lead from ores mined from the Yangtze River valley. The lead certainly benefited the metalworkers: It lowers the melting temperature of the entire alloy, making it easier to work with. But lead didn’t benefit the Shang royals who made ancestral offerings using large bronze ding vessels and drank rice wine out of ceremonial bronze goblets. In 2010, scientists figured out that the acidic wine leached toxic amounts of lead out of the bronze.

The toxic results led one scientist, lead specialist Alan Woolf of Boston Children’s Hospital, to speculate that the Shang princess-general Fu Ha’s mystical visions were hallucinations caused by “encephalopathy due to lead poisoning.” Unlike other toxins, lead quickly escapes from the blood into the brain. Once there, it wreaks havoc by interfering with enzymes vital to brain cells and even reacts with the brain to produce damaging chemicals. A big dose of lead can therefore cause encephalopathy, delirium, and convulsions—not magical powers.

CREDIT: Mountain/Creative Commons

-

Silver coin from Athens depicting the goddess Athena and an owl, 465 B.C.

When scientists examine ancient ice samples from Greenland, they find a thick layer of lead dust from a massive surge in worldwide pollution during the rise of Athens. The Greeks were mining for silver to make their beautiful drachma coins. Before they could mint silver coins, however, the Greeks had to melt the lead out of the silver ore—which was contaminated with as much as 300 parts lead to every one part silver. Unsurprisingly, Greek physician Nicander was the first to describe several symptoms of severe lead poisoning: a painful colic involving nausea and constipation; a weakening of the limbs; and even paralysis of the feet and hands, from destruction of the nerves. However, he didn’t connect these terrible symptoms to this humble silver contaminant.

CREDIT: Odysees/Creative Commons

-

Roman cast-lead pipe with inscription of the Imperial Freeman Procurator Aquarum, the official in charge of the water supply, 100–300 A.D.

For the roughly 400 years corresponding to its peak, the Roman civilization produced 60,000 to 80,000 tons of lead a year—a rate that wouldn’t be matched until the Industrial Revolution. Lead was in water thanks to lead pipes; lead was in food thanks to the lead cooking utensils; and lead was even in the wine, which the Romans sweetened with sapa—a grape syrup boiled down in lead vessels, which imparted the sweet flavor of lead acetate. Over a lifetime of drinking this leaded wine, a Roman could suffer damage to the nervous system, develop anemia, and suffer from infertility—which is why lead has been blamed for toppling the Roman Empire.

To satisfy this hunger for lead, nearly 140,000 Romans worked every year in lead mining and processing. Physicians realized that people who drank water contaminated with mine runoff developed gout—a side effect of lead-poisoned kidneys, which could no longer filter gout-causing uric acid out of the blood. But they didn’t realize that lead was poisoning the entire civilization.

CREDIT: Science Museum, London/Wellcome Images

-

Byzantine lead seal of Constantinople Archbishop Stephen I or II, 9th century

While global lead production plummeted in the West after the Roman Empire fell, the metal continued to be enthusiastically mined in the East by the Byzantines. Malleable lead was the perfect metal for creating official seals. But its use exacted a lethal cost: The skeletons of slaves and criminals condemned to mine copper and lead in southern Jordan had up to 70 times more lead than people who didn’t mine. And those were the fortunate miners who survived long enough to incorporate lead into their bones; the Bishop Eusebius wrote that the mines were normally a place “where even a condemned murderer may live only a few days.”

CREDIT: Photo illustration by Slate. Images courtesy of Cplakidas/Creative Commons.

-

The Libyan Sibyl by Michelangelo, 1512

Chemically speaking, lead is a great choice for paint: Lead compounds—from white lead carbonate to yellow lead chromate—resist cracking, degradation, and moisture. Toxicologically speaking, lead is a terrible choice for painters. After a lifetime of licking brushes and breathing paint fumes, famous artists such as Michelangelo and Caravaggio developed “painter’s colic” and even “painter’s madness” from lead poisoning. Paintings by and of these Renaissance masters often show the limb-wasting and gout caused by their chronic exposure to lead paints.

CREDIT: Painting by Michelangelo. Image courtesy of Lily15/Creative Commons.

-

Beauty, a painting of a geisha, by Japanese artist Gion Seitoku, early 19th century

A startlingly white face became fashionable in two very different places at nearly the same time: 17th-century Edo Japan and 16th-century Elizabethan England. In Japan, wealthy women painted their faces white with white lead—which sent their bone-lead levels through the roof. Wealthy children were severely poisoned from contact with their mothers’ lead. Because lead irreversibly harms children’s developing brains, scientists speculate that the Shogunate collapsed because of its brain-damaged elite.

At the same time, women in England were painting their faces white with a mixture of white lead and vinegar called ceruse. Despite ceruse’s known side effects—hand trembling, baldness, and occasionally death—the painted white face remained popular until the Victorian era.

CREDIT: Painting by Gion Seitoku. Image courtesy of Brooklyn Museum.

-

Tavern Scene, by the Flemish artist David Teniers, 1658

While outbreaks of a condition known as colica Pictonum had stricken wine drinkers since the Roman Empire, it was only in 1697 that German physician Eberhard Gockel linked the colic to wines sweetened with sapa, the grape syrup boiled down in lead vessels. The colica Pictonum inflicted sufferers with headaches, stomach pains, and constipation, followed by paralysis, blindness, insanity, and even death. Outbreaks of the remarkably similar “Devonshire colic” offed English cider drinkers throughout the 18th century, until Sir George Baker traced the cause to lead-lined cider presses and the lead weights added to casks to sweeten the cider. Gockel and Baker were among the first to identify lead poisoning in people who didn’t mine or work with lead.

CREDIT: Painting by David Teniers the Younger. Image courtesy of National Gallery of Art.

-

Skulls of the crew from the doomed Franklin expedition, 1845

The Franklin expedition’s quest to find an Arctic sea route was doomed for many reasons, and lead poisoning was just one. When scientists recovered and examined the crew’s remains in 1981, they found that the skeletons had 10 times more lead than local Inuit bones. The source of the lead remains controversial, but the main suspects are either the lead solder used to seal the crew’s tinned food, or the lead pipes used on the expedition’s ships.

CREDIT: Library and Archives Canada

-

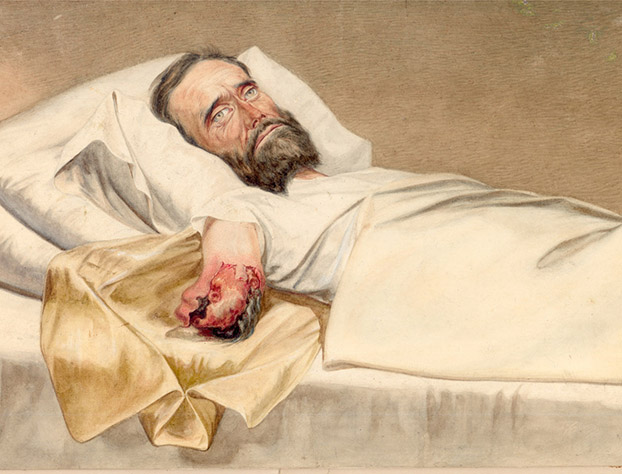

Medical illustration of a wound suffered by Pvt. Milton Wallen of the 1st Kentucky Cavalry, 1863

Not all of lead’s victims are poisoned. “The earliest projectiles for weapons were all lead,” says chemist Eloise Young of NineSigma, “because it was easy for people to take the lead, melt it over the fireplace, and then pour it into the mold” to make bullets.

Invented by the Frenchman Claude-Etienne Minié, the Minié ball was a cone-shaped ball of lead with a hollow base. Its grooved sides helped it travel farther and more accurately than round shot. When these soft, fast-moving balls struck humans, they tore apart flesh and splintered bone. Minié balls caused about 94 percent of all Civil War injuries treated by surgeons, with many traumatic injuries requiring amputation.

CREDIT: Otis Historical Archives/National Museum of Health and Medicine

-

Logo for the Dutch Boy Group white lead paint, early 20th century

Since the 19th century, children in Queensland, Australia, had been coming down with lead poisoning, but doctors couldn’t figure out how. Then in 1904, a doctor named J. Lockhart Gibson proposed that the lead paint used in homes was the source—after he examined a toddler who’d eaten the sweet chips flaking off lead-painted walls.

In the 1920s, American doctors caught up with their Australian colleagues and started linking child poisonings to lead paint on toys, cribs, and woodwork. However, scientists believed that most children would recover just fine—until a depressing but influential study in 1943 showed that lead permanently damaged children’s brains.

In 1977, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission finally ruled that house paint couldn’t contain more than 0.06 percent of lead, more than half a century after Great Britain, Cuba, and Tunisia had banned lead house paint.

CREDIT: Thester11/Creative Commons

-

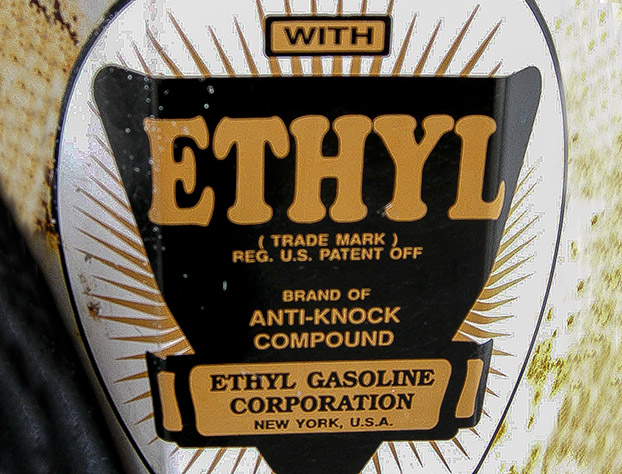

Advertisement for leaded gasoline, 20th century

In the 1920s, engineers at General Motors figured out that adding tetraethyl lead to gasoline boosted its octane rating and allowed them to develop better engines. GM marketers would later call lead “a gift from God,” and tetraethyl lead would be used for the next 50 years in American gasoline—despite early concerns. Some of the first workers to manufacture the additive became floridly psychotic; at least five died. For a long time, manufacturers argued that lead was only poisonous at the high levels experienced by sloppy, careless workers.

But the tide started turning in 1965, when studies uncovered lead’s effects on the public. In 1975, the Environmental Protection Agency started the gradual removal of lead from gasoline over the next 25 years. Since the phase out of leaded gasoline and the banning of lead house paints, the average blood-lead levels in American children have dropped more than 87 percent.

CREDIT: Plazak/Creative Commons

-

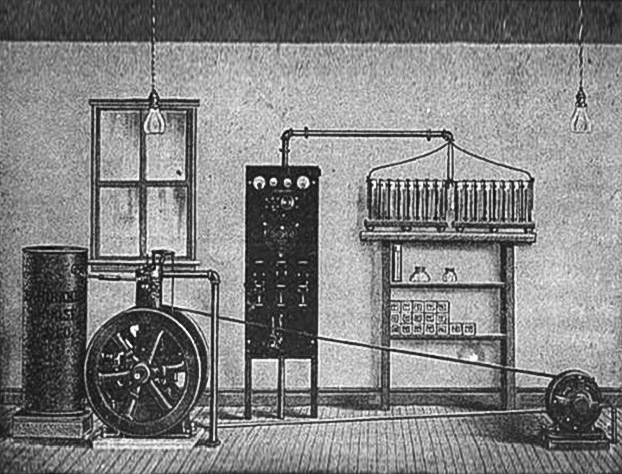

An early direct current generator attached to a lead acid battery, 1917

Surprisingly, the first rechargeable battery was developed more than a century and a half ago. French physicist Gaston Planté fashioned his battery from a linen cloth sandwiched between two spiraled lead sheets and immersed the contraption in a glass jar full of sulfuric acid. The lead plates were then hooked up to a current generator to be charged.

Planté’s lead-acid battery continues to be popular: Nowadays in the United States, lead is mostly used to make car batteries. But battery manufacturing and recycling exacts a high cost. Most American lead pollution originates now from battery manufacturing, which can raise the blood-lead levels of plant workers and children who live near the plants.

CREDIT: Nehemiah Hawkins/Hawkins Electrical Guide

-

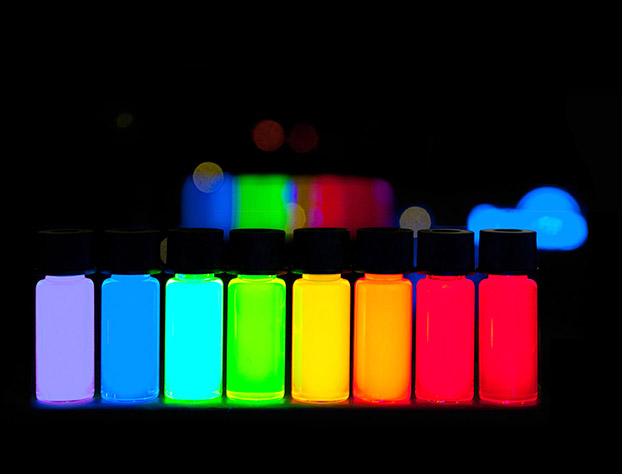

Quantum dots under development for use in computer screens, 2012

First developed in the 1980s, quantum dots are incredibly tiny chemical shells built around a core of cadmium or lead. By tweaking their size, scientists can change the color of light the dots emit when exposed to light or electrical current. Recently, scientists have been figuring out how to take advantage of these nanoparticles in energy-efficient displays and highly efficient solar cells. “Lead can be very useful,” says solar chemist and assistant professor Amanda Morris of Virginia Tech, “if you have a person responsibly working with it.”

CREDIT: Antipoff/Creative Commons

-

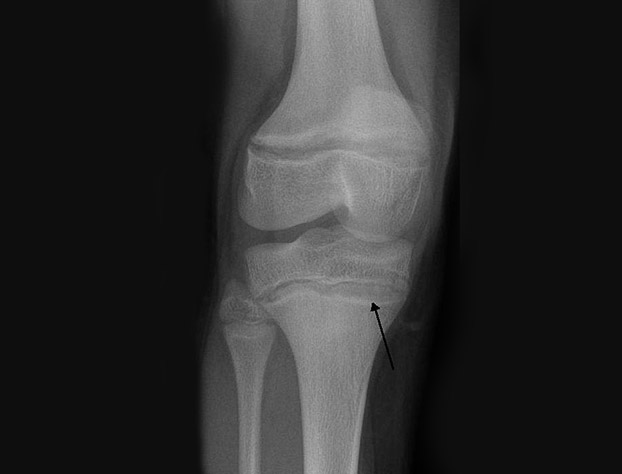

Lines in bone characteristic of lead poisoning, now

The trouble, of course, is that for 6,000 years we have not worked responsibly with lead. And our mistakes stay with us: Instead of degrading, lead accumulates in ice, in soil, and in us. Given our appetite for using lead in everything from piping to bullets to quantum dots, it’s no surprise that this element continues to wreak toxicological havoc. Lulled by its dull, gray, unassuming helpfulness—so unlike fluid mercury or homicidal arsenic—we keep inviting it into our blood, our brains, and even our bones.

CREDIT: Abhijit Datir/Radiopaedia.org