Losing Ground

The Everglades is the site of America’s biggest battle against climate change.

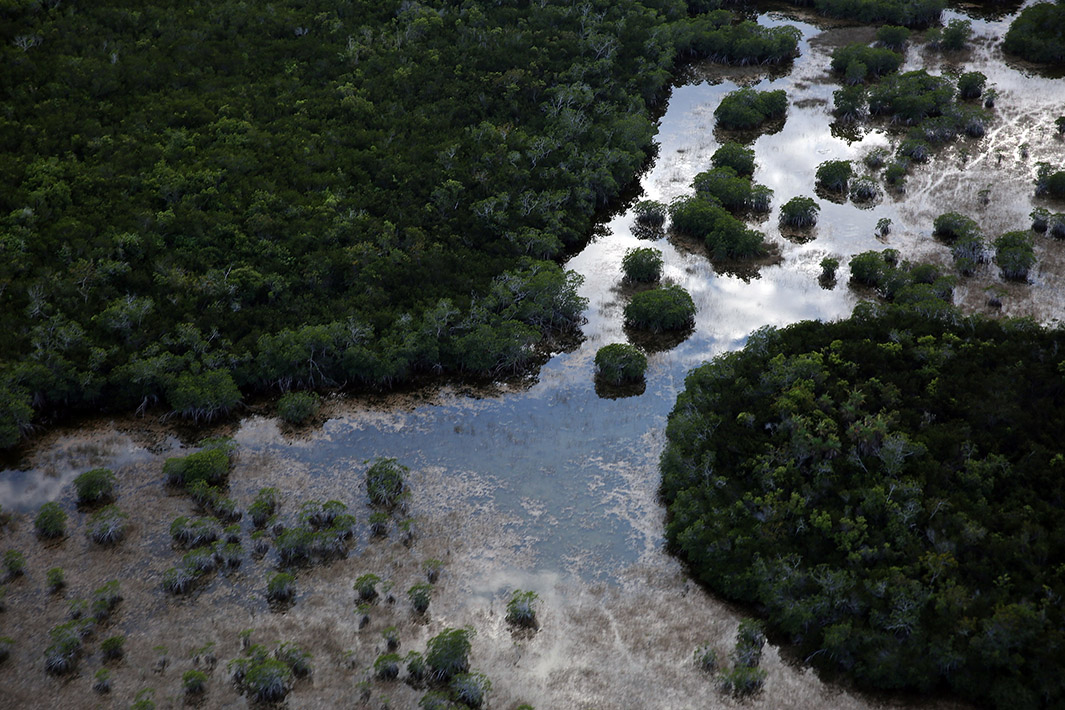

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

On Wednesday—Earth Day—President Obama is traveling to Florida to give us an update on climate change. He picked the right setting: the Everglades. But for the scientists who’ve been working on restoring the health of the Everglades for decades, it’s time for something more than just speeches.

Right now, South Florida is in the midst of a record-setting springtime heat wave. A nearly 2,000-acre wildfire has been burning this week on the outskirts of the Everglades in the face of the summerlike temperatures. Earlier this year, cars floated through Miami streets as the city bore 10 inches of rain in just a few hours.

But it doesn’t even take rain to flood Miami these days—a high tide on a clear day in October 2012 produced a bigger flood than a hurricane that hit just 13 years earlier. According to an analysis of tide gauge data by Brian McNoldy, a meteorologist at the University of Miami, the pace of sea level rise in South Florida has more than quadrupled over the last five years compared with the previous 15. Climate change is already changing Florida, and it’s happening fast.

The mounting evidence is terrifying scientists who, after years of delays and funding shortfalls and political jabs from federal and state officials, can do little but watch as the encroaching sea slowly transforms the state’s marshes and swamps into open ocean, inch by inch.

The Earth Day event is being billed as a legacy speech for a president who has staked his reputation partly on his environmental record. And it’s symbolic that he’s talking about global warming in a state that has produced several high-profile climate-denying politicians.

In a preview of his speech on Saturday, Obama said “there is no greater threat to our planet than climate change,” a problem that “can no longer be denied or ignored”—an obvious dig at Florida’s high-profile presidential hopefuls Sen. Marco Rubio and former Gov. Jeb Bush.

Florida’s leading politicians have turned inaction on climate change into an art form, with some, including Rubio, even bragging about their ignorance on the issue by declaring “I’m not a scientist.” Current Florida Gov. Rick Scott apparently instituted an audacious ban on state officials even mentioning the terms global warming and climate change (which has produced some awkward public meetings), though he denies the policy formally exists.

On Friday, Bush at least admitted that he was “concerned” about climate change, distancing himself from more extreme views within his own party.

Obama couldn’t have picked a better place to showcase how frustratingly complicated it’s been for America to take effective steps toward preparing for climate change. (The mayor of South Miami recently proposed that the south part of the state secede to protest inaction on climate change.)

The Everglades are the subject of a multibillion-dollar comprehensive restoration plan, but 15 years in, there’s been precious little to show in terms of progress.

Originally conceived in the 1990s as a response to the short-sighted U.S. Army Corps of Engineers flood control projects of the mid-20th century, Everglades restoration has since had an “incredible number of glitches, problems, funding delays, congressional foot-dragging, you name it,” says the Tampa Bay Times’ Craig Pittman, who has covered the topic extensively.

As of 2015, only 13 of the 68 original projects that were part of the 2000 Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan have been federally authorized. What was supposed to be a $7 billion, 30-year project has since doubled in expected cost and may not be finished until 2050. By then, climate change is expected to produce a $40 billion hit annually to South Florida’s tourism industry, according to a recent federal study.

Lance Gunderson, an environmental scientist and South Florida native now at Emory University, contributed research that helped motivate the original Everglades restoration legislation in 2000. Since then, Gunderson says, political support for the Everglades restoration has been “all over the map,” with even local representatives voting against it at times.

After the Florida housing crash in 2008, Gunderson says “state budget went to shambles,” and lots of scientists in the state water management districts, which are funded by property tax revenues, were laid off. Now, in the face of climate change, he’s pessimistic and thinks that all the setbacks may have finally amounted to a death sentence for the ultimate vision of Everglades restoration. “Quite frankly, I don’t think they’re ever going to get there,” he said.

But there are a few signs of success. During the 1960s, the Corps converted the winding Kissimmee River into a 56-mile drainage canal (whimsically named C-38) in the name of flood control. The impact on birds and other species that lived along the river was disastrous. By later this year, the river’s bends will be back, and the birds already are. The project is now a model for successful wetlands restoration.

Another hopeful project that’s underway is converting the Tamiami Trail—the first road across the Everglades, built in 1928—into a long bridge. The Everglades are sustained by a “river of grass,” a miles-wide and inch-deep flow of fresh water that is the lifeblood of the swamps of South Florida. Since its construction, the Tamiami (named for Tampa and Miami, its two endpoints) has served as an effective dam of southward flow of water. Raising the road would provide “almost immediate relief to Everglades National Park, which has been starved for water for decades,” said Pittman.

Still, many question whether the Everglades are a lost cause. After all, the Everglades are already sinking into the sea—literally.

“Sea level rise is probably a bigger problem in Florida than any other state,” said Pittman. “We are the flattest state. We are flatter than Kansas.”

At the Ernest Coe Visitor Center in Everglades National Park, where Obama will be making his address Wednesday afternoon, the elevation is 4 feet above sea level. Given current midrange sea level rise scenarios, the ground the president will be standing on will likely be underwater should a big hurricane strike in the 2050s, and could be submerged on a clear day by 2100.

What’s more, sea level rise is already causing “basically a collapse, or breakdown, of the soil” along the fringes of the Everglades, says Steve Davis, a wetland ecologist at the Everglades Foundation. That means that at the same time sea level is rising, ground elevation is sinking due to saltwater intrusion.

The geology of the region exacerbates this problem. Porous limestone allows saltwater to percolate up from below, infiltrating the freshwater aquifer. Drinking wells have already been contaminated with seawater in the Miami area, and the city is investing in an elaborate system of pumps to keep its water supply fresh.

One of the key goals of Everglades restoration is to increase the total volume of freshwater in the Everglades and South Florida, from Lake Okeechobee in the north to the Keys in the south. Since freshwater is less dense than saltwater, it floats on top of and pushes down against seawater. The hope is that more freshwater will form a partial barrier against sea level rise, forcing the intruding ocean back toward the coasts.

Currently, a system of 60-year-old canals and drainage ditches channel freshwater toward the coasts and into the ocean, providing little benefit to the swamp. “By putting that water back in the Everglades instead of sending it to the east and the west, it helps to fill that bubble of water underneath us with freshwater,” said Davis.

The growing appreciation that the Everglades will be lost to the Atlantic has likely paused steady restoration funding over the years, but scientists working on the project say, if anything, just the opposite should be true. There’s a lot of benefit in acting to buy a couple of decades.

According to nearly every scientist I spoke with, the worst-case scenario at this point is continuing to do nothing. That fact is leading to a change in the way science is being done in South Florida.

To date, science supporting Everglades restoration has focused mostly on modeling the impacts of proposed actions. For Nick Aumen, an aquatic ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, that’s not enough.

“We know that the system is under stress,” said Aumen. “In any situation like that, the faster you move the more likely your chances for success are.” In the case of the Everglades, “the consequences of not doing anything are greater than taking the risk of making some moves, and then learning and continuing to collect good scientific information as we go along.”

By chance, Aumen this week is chairing a biennial scientific meeting on Everglades restoration, with 530 people in attendance. So far, the buzz at the conference was excitement for the president’s visit, but more importantly, a desire to turn words into action.