It’s so nice to be needed even after you’re dead. That’s what I was thinking during the rehearsal dinner for Pocahontas and John Rolfe at the Williamsburg Lodge, off Route 60 in Virginia.

Photo courtesy Preservation Virginia (Historic Jamestowne)

In 1614, Rolfe, a tobacco farmer and recent widower, needed Pocahontas, the object of his obsession, for, well, sex. Chief Powhatan needed Pocahontas, his daughter, to wed this English colonist to secure Powhatan’s sovereignty over his chiefdom. Years after Pocahontas’ death, former Jamestown leader Capt. John Smith needed the Indian princess’s legend to secure his own fame. During the Colonial era and beyond, Virginian and British families used their genealogical connection to her to claim highborn heritage, and after the Civil War, the local Indian community used her to protect itself from deeply racist Jim Crow laws. Historic Jamestowne needs her today to promote tourism. And as I learned from the current chief of Pocahontas’ tribe, the Pamunkey still need her to protect fishing rights and help secure federal recognition.

Pocahontas had shellfish embroidered on her wedding jacket, which was modeled on a garment from the era in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. According to a volunteer embroiderer at my table, it took 70 volunteers (including former Virginia first lady Roxane Gilmore) 55 days to stitch 130 pretty black creatures, including rabbits, deer, and crabs.

Her jacket worked a lot better than John Rolfe’s red suit, which, while historically accurate, looked disco-ish even topped by an oversized black hat.

The event would have resembled any generic upscale hotel wedding rehearsal dinner if it weren’t for the three Native American men on a dais wearing tanned buckskin and draped in raccoon mantles, their skin covered by red and blue body paint.

The next day’s wedding re-enactment was to be held at the base of the original mud-walled chapel where Pocahontas wed John Rolfe on April 5, 1614—400 years later to the date. The site of the settlement’s chapel was found just in 2010 at Historic Jamestowne. Its perimeter exactly matched dimensions described by William Strachey, secretary of the first English colony in the New World. The discovery was acclaimed as one of Archaeology magazine’s top 10 finds of the year.

(To clear up a common misconception for those who live outside Virginia—four out of five college graduates I polled in an East Village Starbucks got this wrong—Capt. John Smith, leader of the Jamestown settlement, who claimed Pocahontas saved him by begging her father to release him moments before certain death, was never married to Pocahontas. He left Jamestown after being injured by a gunpowder explosion, never to return. Farmer John Rolfe departed England in 1609 on the third supply fleet headed to the struggling English colony. After a short stint as a castaway in Bermuda, he arrived in Jamestown in 1610 and married Pocahontas four years later.)

I wasn’t out of place in a room full of Pocahontas enthusiasts. I was the girl who dressed up for Halloween in a fringe dress and braids telling everyone I was an Indian princess. My favorite picture book was Pocahontas: A Little Indian Girl of Jamestown, which described Capt. John Smith as a handsome “Paleface” hero “straight and tall” with hair “the color of gold leaves in the autumn, his eyes like the sky.” Smith told Pocahontas stories and gave her prized gifts, such as a hand mirror. She in turn walked through the forest to warn the captain that her tribe would kill him while he slept. I took out every children’s book about Pocahontas I could find in the library and questioned my mother, who as a girl had also dreamed of being Pocahontas. I was sure Smith loved his little friend back, but she was born too late. She obviously married the wrong man, and did so only because she was told the right one was dead. When she lived in England as the new Lady Rolfe, she saw Smith once, and what a tragedy that must have been! If only he had waited for her to grow up to marry him.

In 2005 I couldn’t wait to see Terrence Malick’s visually sumptuous (if a bit plotless) two-and-a-half-hour film about Pocahontas and the Jamestown colonists. I could convince absolutely no one to go with me.

When I read about the wedding re-enactment, I’d been especially intrigued that a member of Pocahontas’ Pamunkey tribe had been chosen to portray her. Had the local Native Americans really signed off on this event? I decided I had to attend.

Once again no one wanted to accompany me to a Pocahontas event, not even my 11-year-old daughter, who said she was slightly embarrassed for me. I made the triumphal announcement to my family that I was going alone. “Bring me back a T-shirt,” my daughter said without looking up from Instagram.

It was easy enough to get to the wedding, a straight eight-hour train ride from New York’s Penn Station to Williamsburg, Virginia. There was a free shuttle bus from the 18th-century Colonial Williamsburg to 17th-century Jamestown, 15 minutes away. But how was I going to get an indigenous perspective unfiltered by pomp and press releases?

It was simpler than I thought. Wandering around the grounds of Colonial Williamsburg, the first person I spoke with was Jeff Brown, an archaeologist digging by a slope near a cobblestone street. “You have to call my brother Kevin, I swear, he’s the current chief of the Pamunkey tribe.”

“I am the chief,” Kevin Brown said firmly over the phone, and added that he would have plenty to say on the wedding matter.

With the clomping of horses in the background, I made arrangements to meet him the next day in the upstairs bookstore café at the College of William & Mary. “Look for a man with a beaded pendant on his neck.” Then he gently advised me, “You really don’t have to keep saying ‘Native American’ in Virginia. We use the word ‘Indian’ here. Or we just name the tribe.”

I didn’t want to be uninformed going to an unexpected meeting with a tribal chief, so I quickly read up on the unusual status of Indian tribes in Virginia. In 1924 an astonishing law was passed called the Racial Integrity Act that restricted who could marry based on race. Anyone with a hint of black ancestry was considered black and prohibited from marrying a white person. But according to a subsection of the law known as the Pocahontas Exception, since the oldest Virginia families claimed descent from Pocahontas, a person with one-sixteenth Indian blood was considered white.

The law protected Native Americans somewhat from Jim Crow laws. But the long-term unintended effect of classifying people with Native American ancestry as white is what Laura Feller, a curator for the National Park Service and the foremost expert on this ugly asterisk of history, has termed “administrative genocide.” It has left “a modern-day legacy where today’s Virginia tribes struggle to achieve federal recognition because they cannot prove their heritage through historic documentation.”

Chief Kevin Brown was indeed sporting a colorful pendant the next day over his light blue oxford shirt and vest; his head was shaved bald except for a short black ponytail. “The marriage has never been a big story to our community,” he said. “A lot of little girls lived then who wed white men. Many other chiefs ruled beneath Powhatan, who used his children as a way to secure allegiances. He had as many as 50 daughters, and Pocahontas was not of as high a station as some of the other girls were. He had a child of his living at almost every tribal community, and viewed Jamestown as another opportunity to secure influence. Influence was currency back then.”

Image courtesy Library of Congress

Brown made intimidatingly direct eye contact. “I’ve anguished over this weekend, but the Pocahontas connection helps our fight for federal recognition,” he said. The tribe is already recognized by the state of Virginia, and it is on track to be the first federally recognized Virginian tribe sometime in 2014. With that designation comes enormous economic potential.

The Pamunkey are one of the many related tribes classified as Algonquian. In 1607, when the English arrived, about 20,000 local Algonquian-speaking Indians called Powhatan (after their leader, Pocahontas’ father) lived near the Virginia coast. Of these Indians, about 1,000 of them were Pamunkey. About 160 European settlers lived in the village of Jamestown. Today there are 205 Pamunkey, and 50 people live on the 1,200-acre reservation in King William, about 40 miles away from Historic Jamestown on the banks of the Pamunkey River. It was set aside by treaty in 1646 and given to the tribe in 1658. On the reservation is a burial mound thought to hold Powhatan’s remains.

“We did talk to trees,” Brown said of the Disney film Pocahontas, “but the rest of the story is BS. Disney came to our reservation for research. I don’t think anyone got any money. We didn’t. Honestly, I’m going tonight for the meal, and I’m a little pissed the big rehearsal dinner’s not an open bar.”

He worried his reply was too frank, but I reassured him I wanted the truth, and then he smiled warmly. “I’m trying. I really am. If I can use these things as a platform to get out that my tribe’s fishing rights are under attack, I’ll go along with it. The Pamunkey and the Mattaponi have always had exemption to fish shad and catfish, and now the Department of Game and Inland Fisheries wants to curb our rights.” He explained that they signed a treaty for these rights in 1677, and tribal fishermen always carry cards that identify them as Pamunkey. “They say the shad is overfished and there’s mercury danger, but these are our rights by treaty.”

The Pamunkey, he said, have run a shad hatchery since 1918. Along with the Mattaponi tribe, the Pamunkey have worked to increase fertilization by 60 percent by taking the female fish and squeezing their roe into pails and then catching a male fish and adding his sperm.

“So if people look at our participation this weekend like ‘What a bunch of sellouts!’ they are not seeing the big picture. If you want justice to work, you have to be at the table. Four or five years ago, we got more involved with the events produced through Colonial Williamsburg. Before that no one particularly recognized or appreciated our existence, but they are starting to. That’s why I said yes.”

Pocahontas was born about 1595 in Werowocomoco, 15 miles upriver from Jamestown. She was about 11 when she met 27-year-old Smith. Smith’s account is the primary historical record of her childhood, but it is so strewn with inconsistencies that, as historian Camilla Townsend hypothesizes, most of his thrilling account of a girl begging her father to save a white man was a spin on Indian maiden sexual fantasies popular at the time.

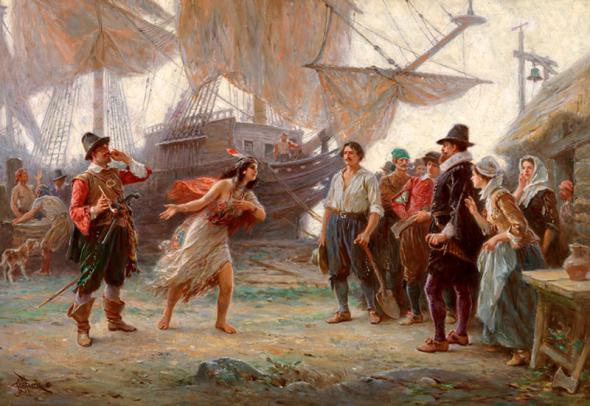

Painting by Sidney E. King/National Park Service

But no Jamestown experts have disputed that the most famous marriage in American history took place. The first church-sanctioned interracial marriage in English-speaking North America was huge news on both sides of the Atlantic. And it ushered in a seven-year period of peace and unity between the colonists and Indians before renewed war.

Apparently I was the first of 120 guests for the rehearsal dinner; when the doorman opened the entrance for me, he asked if I was going to the Edwards/Carlisle wedding.

I explained why I was there.

“Oh dear, I forgot Miss Pocahontas is getting married tomorrow. The Rolfe party is in the Colony Room, down the hall to your left.”

Few regular visitors to Colonial Williamsburg had bought a ticket, at $95 a seat. Over cocktails I met loyal staff, wealthy board members of Colonial Williamsburg, and local “Pocahontas descendants” who identified as white and Protestant. For 400 years, American bluebloods in the thousands have claimed direct descent from Pocahontas via her son, Thomas Rolfe, and his daughter Jane. There were the Byrds, a family of famous explorers and governors, New York City’s handsome former Mayor John Lindsay, Woodrow Wilson’s wife Edith, mathematician and astronomer Percival Lowell (who thought he found canals on Mars), and Nancy Reagan, who favors astrology over astronomy. In England there are scores of additional fancy folks proudly touting Pocahontas lineage through Thomas’ other daughter, Anne.

Photo courtesy Preservation Virginia (Historic Jamestowne)

Three Jamestown colonist re-enactors entered the room accompanied by the three Indians in buckskins and body paint.

Then swarthy John Rolfe arrived with his comely bride-to-be, her hair bunned and tucked into a bonnet.

A man acting the part of the colony’s Anglican minister Richard Bucke led us in a severe 17th-century form of grace, and everyone in the room bowed their heads. Oy. Was I the only secular Jew there? Did no one care that “Bucke” was an actor? After another culture-shocked glance around the room, I bowed my head, too.

Between each dish served, the historic interpreters on the dais gave a few lines of scripted dialogue. One maid was a composite of the English women who tended to Pocahontas after she became Lady Rolfe.

The menu, starting with cornmeal-crusted oyster chowder, was purported to be what could have been served in 1614, but there was no bottle-nosed dolphin served, nor shark, whale, turtle, snake, heron, eagle, crow, skunk, dog, horse, or cat.

Was Chief Brown suffering? I squinted over to his table, and it was hard to tell. Toward the end of my sweet potato tart dessert, I strolled over to say hi, and he introduced me to his good friend, Robert “Two Eagles” Green, a former insurance executive and chief emeritus of Virginia’s Patawomeck tribe, who portrayed Pocahontas’ father, Powhatan, in an episode of PBS’s Nova.

Brown then presented me to Buck Woodard, a ponytailed anthropologist with a charismatic George Clooney smile. When I’d spoken with Brown at the bookstore, he said that he decided to come to the weekend’s festivities in part because Woodard “asked me to participate, and I trust him and listen to him.”

“The two tables of Indians here are my guests,” Woodard said. “Of course they didn’t pay to come. I’m honored that they did come.” Woodard is an adjunct professor at Virginia Commonwealth University’s School of World Studies and director of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s and Historic Jamestowne’s American Indian Initiative. “The dinner was a tough sell,” Woodard confessed.

A clamorous crush of well-wishers started seeking to have their pictures taken with the famous couple. Woodard and I agreed to talk more at the wedding the next morning.

Before entering the old coastal fort, I signed the wedding guest book. After making sure I didn’t see any of the Indians I had been talking to at the rehearsal dinner, I asked another tourist to take a photo of me touching Pocahontas’ hand for good luck. As a child I’d seen pictures of this 1922 life-size statue by the fort’s entrance, sculpted by William Ordway Partridge. As an adult I could see how it might offend: This beauty with a feather in her hair has European features as in a Degas ballerina sculpture, and she wears clothing from a Western tribe. The iconic statue is copper-green, with both hands rubbed to a shine from so many people superstitiously touching them. The governor of Virginia presented a replica in 1958 at St. George’s Church in Gravesend, England, where Pocahontas died in March 1617, after being left off a ship with what was probably tuberculosis. She had just finished a year abroad with her husband, including a formal presentation to the royal court as the baptized Lady Rebecca Rolfe. She is buried under the chancel in Gravesend, where the important locals were placed after death, and her remains have never been disturbed or studied.

I bought a southerly sweet tea inside the small standalone cafeteria and added a $1.25 slice of white-frosted “Pocahontas wedding cake” to stay festive.

In a blue short-sleeved work shirt, archaeologist David Givens talked to passersby from the cellar of the fort, where he was busy unearthing a brick bread oven. Watching archaeologists work on site is part of the Jamestown attraction. A clutch of wedding guests crammed near me to take photos of Givens.

Painting by Sidney E. King/Image courtesy National Park Service

It’s been a strange time for archaeologists at Jamestown. Just over a year ago, Smithsonian scientists announced that they had discovered the partial skull and severed shinbone of “Jane,” a 14-year-old girl, near the Jamestown chapel. The bones bore the marks of an inexperienced butcher. These mangled human parts were direct evidence of cannibalism during the harsh winter of 1609–1610, referred to as the Starving Time. The announcement brought on a media storm and rare mentions of dismemberment on TripAdvisor.

Givens told the tourists, all the while sifting soil, about the discovery of half-eaten Jane. Another thing archaeologists there have shown is that what masters eat, servants eat. “Archaeologists and scientists see a lot of lead poisoning; both masters and servants were eating off the same pewter plates.”

After answering a few more enthusiastic cannibalism questions from the dozen or so visitors standing above him and passing time before the ceremony, Givens tried to describe his other work, dropping words like mitochondrial and isotopic signatures. After a polite silence, it was back to more cannibalism questions.

“The softer expression for cannibalism is processing to be eaten,” he said resignedly.

Buck Woodard waved me over to continue our truncated rehearsal dinner conversation. He cast the Indians in the weekend’s events. He’s done a lot of film work, mainly as an adviser along with Chief Robert “Two Eagles” Green, and he had the know-how to do the makeup for the Indian characters.

Photo courtesy Preservation Virginia (Historic Jamestowne)

Woodard worked with Native American actress Irene Bedard, who was the voice of Pocahontas in the Disney Pocahontas film and its sequel, Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World. He worked with Q'orianka Kilcher as Pocahontas in the grown-up movie The New World. Was he a fixer on set? “Emmanuel Lubezki, who was nominated for an Oscar as cinematographer for New World”—he won for Gravity—“called me an animateur, and I like that better than fixer. It’s French for the person who makes things comes alive, makes things happen.”

I complimented him on his lapel pin (“Iroquois League”) and his snazzy purple jacket. “Not purple, wampum-colored.” I was so nervous that I would get the Indian perspective wrong that I double-checked if he was being humorous. “Sort of, but wampum and belts were used in diplomatic ceremonies. But think how much of the humor of the Indians participating in the original ceremony may have been lost. I imagine the newcomers transcribed seriously. Indians can be ironic too, ya know. If only we had a linguist working on the subtleties.”

“Isn’t there?”

“Nope, nobody’s meaningfully working on Virginian Algonquian since Blair Rudes died.” I was embarrassed that I had no idea who he was talking about. “An astonishing linguist who worked on The New World. I’m proud that in this ceremony, which is for the dominant culture, there is substantive and meaningful use of Pamunkey words, which Rudes helped bring back from the dead.” Some of the words we know for sure originated from the Powhatan language are raccoon, opossum, pecan, moccasin, hickory, persimmon, terrapin, tomahawk, and wow! “As in powwow,” he explained when I questioned the last one.

So how many authentic words would be used in the ceremony a few minutes away?

Woodard knew: “Twelve. Mostly during a native blessing in which John Rolfe and his bride’s hands will be linked and wrapped with beads by Pocahontas’ uncle Opichisco. But sometimes 12 is not 12. Algonquian phrases are polysynthetic and build like German, so one big, long word can be descriptive of people and place; one Pamunkey word would be many more in English.”

“I see my real job as an ombudsman of the local Indian voice,” Woodard said. “And as far as this weekend goes, Pocahontas is the most famous person in the story, and if we need her to get a level playing field in a dominant culture, then so be it. Just look over at those benches. Twenty Pamunkey Indians are in the fort of Jamestowne, and you tell me, when’s the last time that happened? In the 17th century? I’m not trying to sugarcoat the compromises being made this weekend, but their very presence here is a big deal in post-Colonial American history.”

We stopped talking after two musicians appeared onstage to serenade the audience by viola da gamba and recorder.

A VIP area was roped off along the 24-by-64-foot footprint of the old chapel, a few dozen of us seated inside it, the not-so-fortunate standing outside of it, four deep. In the front left rows, the honored Pamunkey guests fanned themselves with their programs while reporters and photographers from Indian Country Today and the Washington Post snapped photos of a smiling former governor of Virginia.

As the British flag flapped above us, the fanciful procession down the center aisle began, first gallant guards from the fort carrying rifles, then two priests, and then Capt. Samuel Argall, a man of influence at Jamestown. Now the Indian party arrived, the same Native American actors from the rehearsal dinner.

At first sight of the bride, the smartphones came out. Wendy Taylor, with her rich brown hair glimmering in the sun and a smashing Disney hourglass figure, was undeniably the embodiment of all little-girl and grown-man fantasies of Pocahontas. The Pocahontas fangirls around me gasped and grabbed their parents’ hands to steady themselves at her arrival.

I was secretly ashamed that I shared their excitement.

Yet Pocahontas had but one line: “I will.”

Couldn’t the writing staff have added to this? Maybe they were purists. What we know about the ceremony comes from an account by Ralph Hamor, the Jamestown secretary who succeeded William Strachey, and there was no account by Pocahontas. It is wishful thinking that she would have said more.

One thing the children’s books and most Pocahontas myths fail to mention, a fact that sucks some of the romance out of the occasion, is that Pocahontas was kidnapped before the wedding. In April 1613, Capt. Argall captured Pocahontas in the town of Passapatanzy, where she had been calling on relatives. She was held prisoner at the town of Henricus for a year, had Christianity lessons, and was baptized Rebecca. (Whether or not she used the name, she almost certainly ceased being known as Pocahontas, which was a nickname. Her childhood given name was either Amonute or Matoaka; she let it be known around the time of her wedding that she preferred to be called Matoaka.)

It is clear from diaries and records that Rolfe was infatuated with Pocahontas, but zero evidence exists that she shared an emotional connection. It is possible that she agreed to marry the widower as one of the terms of her release.

Capt. Argall, wearing a wireless microphone, laughed arrogantly to his comrade in a stagy aside. “She was traded for a small copper pot!”

Image courtesy Meg Eastman/Virginia Historical Society

A history enthusiast behind me behind me said to his son: “Argall was a jerk. I’m glad that’s coming across.”

After the ceremony, the newlyweds were escorted to the much-needed shade of a craft services holding tent.

A dignified lady seated next to me asked if I’d enjoyed the 20-minute ceremony. She turned out to be Anne Geddy Cross of Hanover, Virginia, president of the Board of Trustees of Preservation Virginia. Cross oversees the site as well as five core historic properties. I assumed she got to meet Queen Elizabeth II in 2007 when she visited for another historical marker, the quadricentennial of the first settlers’ arrival. “I did indeed! Royalty loves to visit Virginia.” But she claimed to be more over the moon that Indian royalty was here this time. “That’s truly something!”

I remembered that souvenir for my daughter when I saw the T-shirt options fluttering in the hot breeze in an outdoor popup shop alongside the James River. One showed Rolfe kneeling by Pocahontas, asking for her hand, with a cringe-worthy scratched heart in a tree that read “Pocahontas + J. Rolfe, 4*5*14.”*

Here I ran into Bill Bolling and his son Sean Bolling, also buying T-shirts. Mrs. Bolling (I never caught her first name) emerged from the tent, saying she’d brought along a chart prepared by an ancestor, Blair Bolling, in 1810 that explained that her husband and son were “red Bollings,” who have the most assured heritage from Pocahontas; others identified by genealogists as “blue Bollings” and “white Bollings” have iffy links.

“Got that correctly?” she asked hopefully.

According to Bill Bolling, his family also has a tradition of naming daughters Pocahontas, and Bill recently found the grave of an ancestor named Pocahontas Bolling. He was thrilled to be at the wedding: “I’m pretty humbled. This is the same site it all happened on. I’m taking it all in.”

Despite misgivings, I bought the shirt with the kneeling Rolfe. I was almost ready to leave when I realized in horror I had not gotten Pocahontas’ perspective from Pocahontas.

Photo courtesy Chuck Durfor

Buck Woodard agreed to introduce me to 25-year-old Wendy Taylor (Chief Brown’s cousin), but only after she had had a decent break. As I waited in the tent, my eyes roved to John Rolfe (actor David Catanese) in his red suit and 17th-century hat sneaking a Tastykake powdered sugar donut from the craft services table. I reached for my iPhone to document this, and he gave me a thumbs-up, then the bride was ready to say hello.

Woodard stood nearby, perhaps to make sure I was asking respectful questions. “I saw the movie Pocahontas I can’t even count how many times. I was always pretending to be her. I love being her,” said Taylor. Woodard looked like he was disappointed that Taylor’s excitement in being cast stemmed from watching a vamped-up maiden in Disney cartoons. But then he put in, “Now that she has a 4-year-old and a 9-month-old, she’s watching it again.”

I was startled and excited to find out that the silver-haired man next to me listening to our conversation was the most famous man at the fort, the archeologist who insisted more than 20 years ago that the fort had not washed away, that its traces could still be found along the James River. Oh my! I had just read his book on the train. Could I interview him, too?

William Kelso happily started in with the story he has told countless times. “I began by myself, 20 acres started by shovel, I then noticed a dark streak in the soil. Man, I was beside myself! Right away I found an object, and we have since found 1.7 million other objects.” None of this would be happening if not for his vision—not the archaeological research, not the World of Pocahontas Unearthed exhibit that opened June 6 at the Jamestown site, not the wedding re-enactment.

“It is something, isn’t it, for it’s on the genuine site? It’s a lovely day, but meeting the Queen, that was my best moment,” he said. In 2007, Kelso was made Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

“I was told the Queen wanted a reflective moment, so I racked my brains for something good to say to her. When I met her, I spent 20 minutes with her guiding her around in her blue coat and blue hat. There was a lot to catch up on since her 1957 visit to the fort. She loved all of it, and I whispered, ‘Your majesty, this is where the British Empire began, this was not just the first American colony, this was the first colony in the British Empire.’ ” He chortled. “She loved that bit of information, she gave the best smile and incorporated that tidbit into her speech. Bush was there, too, you know, but making the Queen smile. That was wild.”

Kelso pointed to where he lives year-round, a building on site, in a caretaker’s house provided by Preservation Virginia. “That’s why I can be here so often. I’m waiting on what the future still holds. Hopefully my career highlight is still ahead. Did anyone tell you work started a few days ago on the western end of the island, 20 unexplored acres? It took us 20 years to dig one acre. So think about that, one acre, 95 percent of the site is uncovered. There is years of work ahead. I’ll fall in my last hole here, probably. I’m too excited to stop.”

On the Amtrak ride home, I worried that I would, like so many before me, convince myself that I deeply understood a complicated history after a glimpsing visit. My reported journey to Jamestown will be hopelessly outdated in 50 years, like all of the accounts I have read, starting with the ones by the settlers at Jamestown who had a late-medieval perspective and offered the world a Christians vs. savages account. Their “good Indian woman who saved the life of a white man” tale is spectacularly loved even today. In other accounts, Pocahontas has been portrayed as a brat at Jamestown; she has been called powerless, and even matter-of-factly a prick-tease. The divide in interpreting her story is not just between cultures; in academic circles, there are still factions with brittle pride warring over whether Pocahontas really saved John Smith from death, whether he made the story up, or whether the narrative was about a ritual drama John Smith simply didn't understand. Some experts argue about the appropriation of Pocahontas as an American Indian woman that the larger public has reduced to a “Pocahottie” Halloween outfit. None of these tropes is centered within a firm Algonquian indigenous worldview, perhaps an almost impossible task 400 years later. Divergent takes on historical events will not always be reconciled.

But even if I went to Jamestown and all my daughter got was a lousy T-shirt, I have gotten so much more out of the pilgrimage.

*Correction, June 23, 2014: This story originally misstated the date on a T-shirt showing John Rolfe proposing to Pocahontas. (Return.)