Is It Time to Tax Harvard’s Endowment?

While state schools suffer and middle-class students drown in loans, elite universities are only getting richer.

Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Wikimedia Commons.

“The joke about Harvard is that it’s a hedge fund with a university attached to it,” Mark Schneider tells me. It’s a quip that, for obvious reasons, has become pretty popular in recent years. In 2014, the university’s legendary endowment, overseen by a team of in-house experts and spread across a mind-bending array of investments that range from stocks and bonds to California wine vineyards, hit $36.4 billion. “They’re just collecting tons, and tons, and tons of money,” says Schneider, a former Department of Education official who is currently a fellow at the American Institutes for Research.

Of course, normal hedge funds have to pay taxes on their earnings. Because it’s a nonprofit, Harvard doesn’t. And since bestowing tax exemptions is the same as spending cash from the government’s perspective (budgeteers call them “tax expenditures” for a reason), that means the American public effectively subsidizes Harvard’s moneymaking engine. The same goes for Stanford (endowment: $21.4 billion), Princeton (endowment: $21 billion), Yale (endowment $23.9 billion), and the country’s other elite institutions of higher education.

Aiding wealthy research universities that cater to largely affluent undergraduates might have been acceptable in a more flush era. But at a time when state colleges are still suffering from deep budget cuts that have driven up tuition and politicians are stretching for ways to make school more affordable for middle-class students, clawing back some of that cash to spend on needier schools is starting to sound awfully appealing. Which is why it might just be time to start taxing Harvard and its cohort.

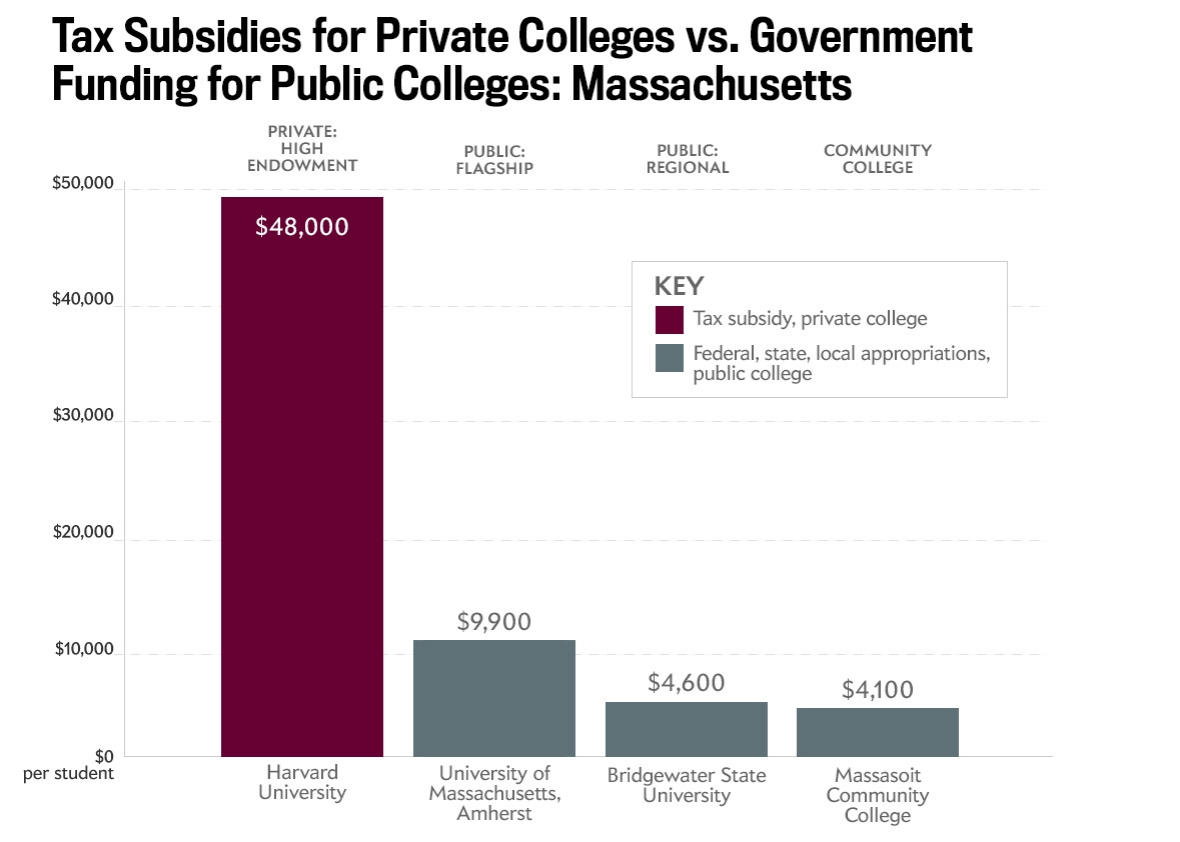

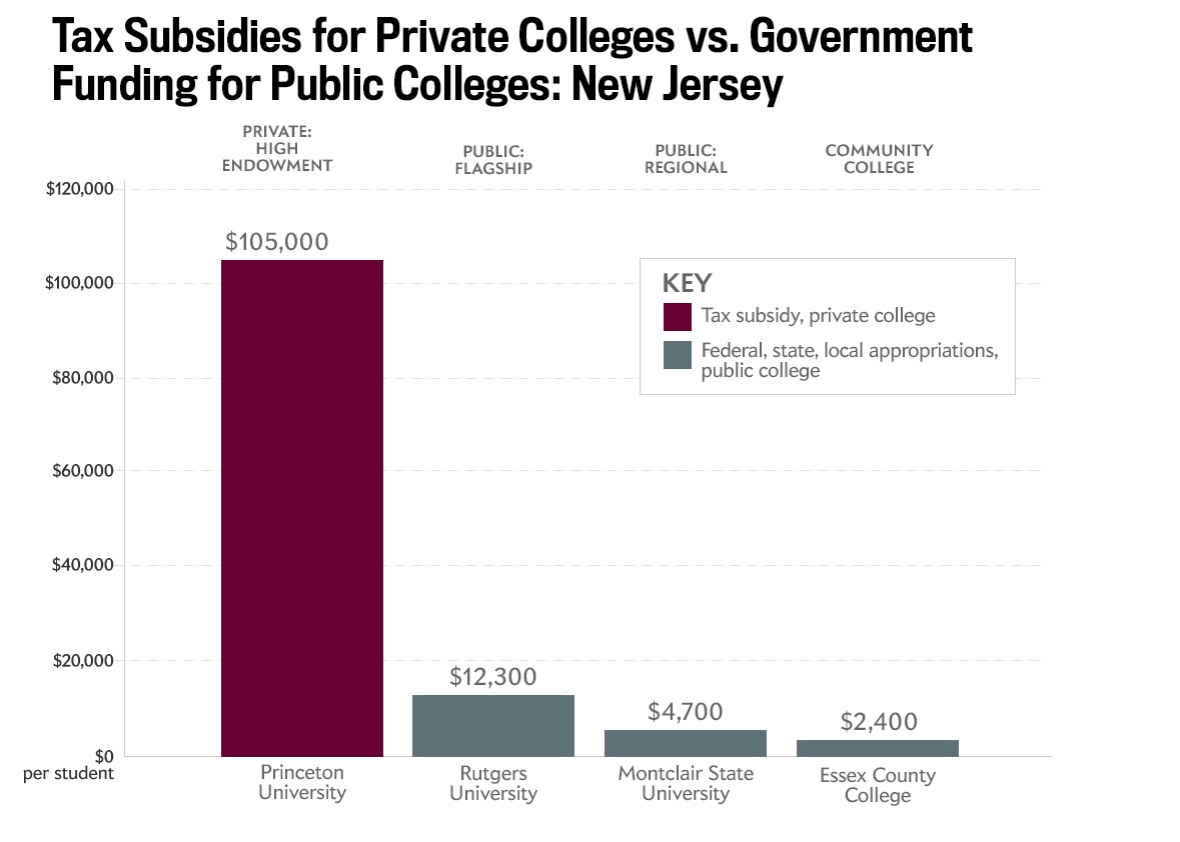

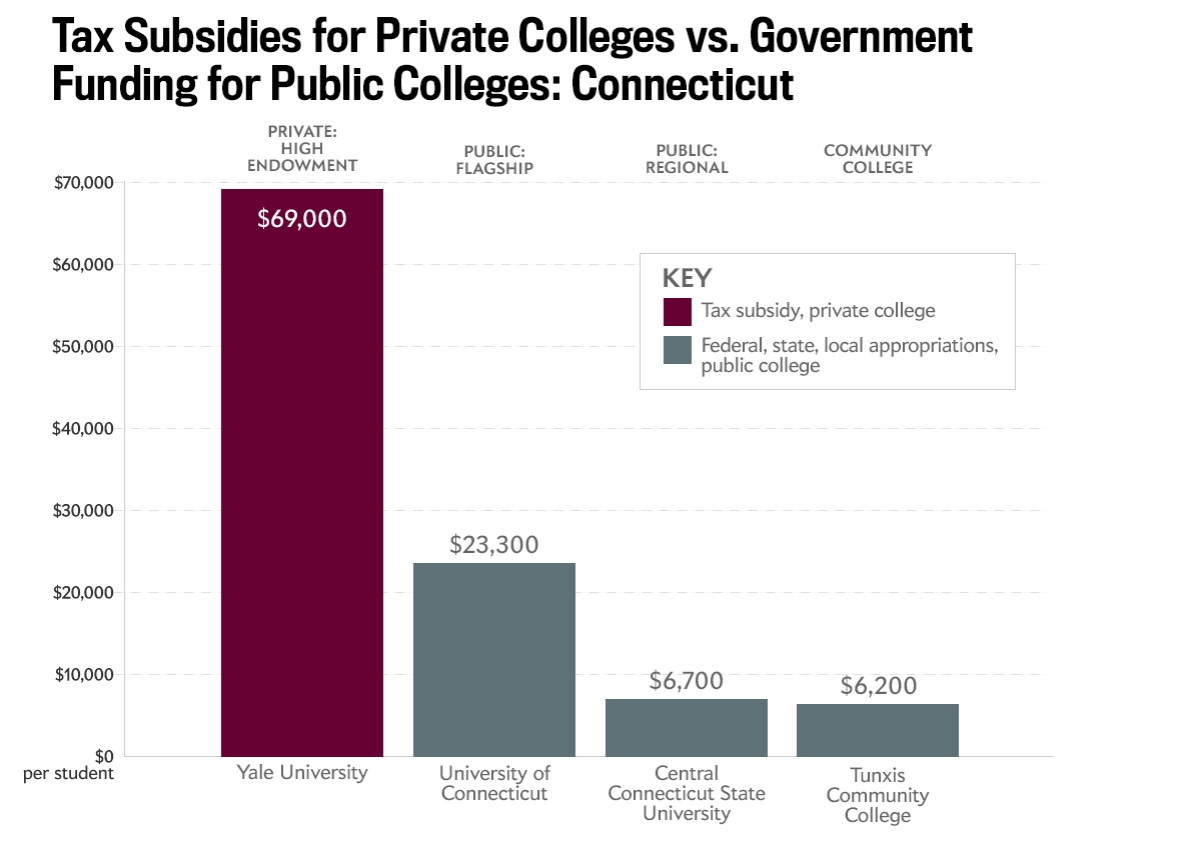

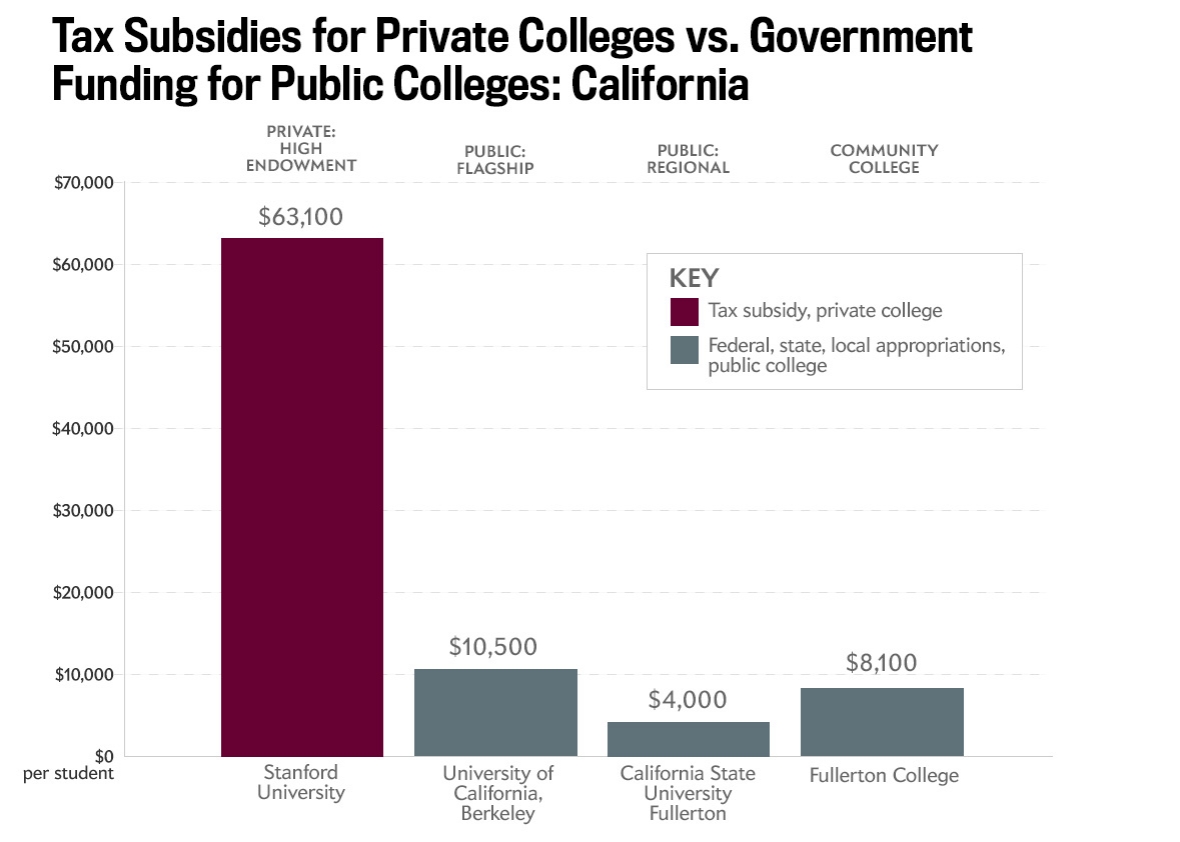

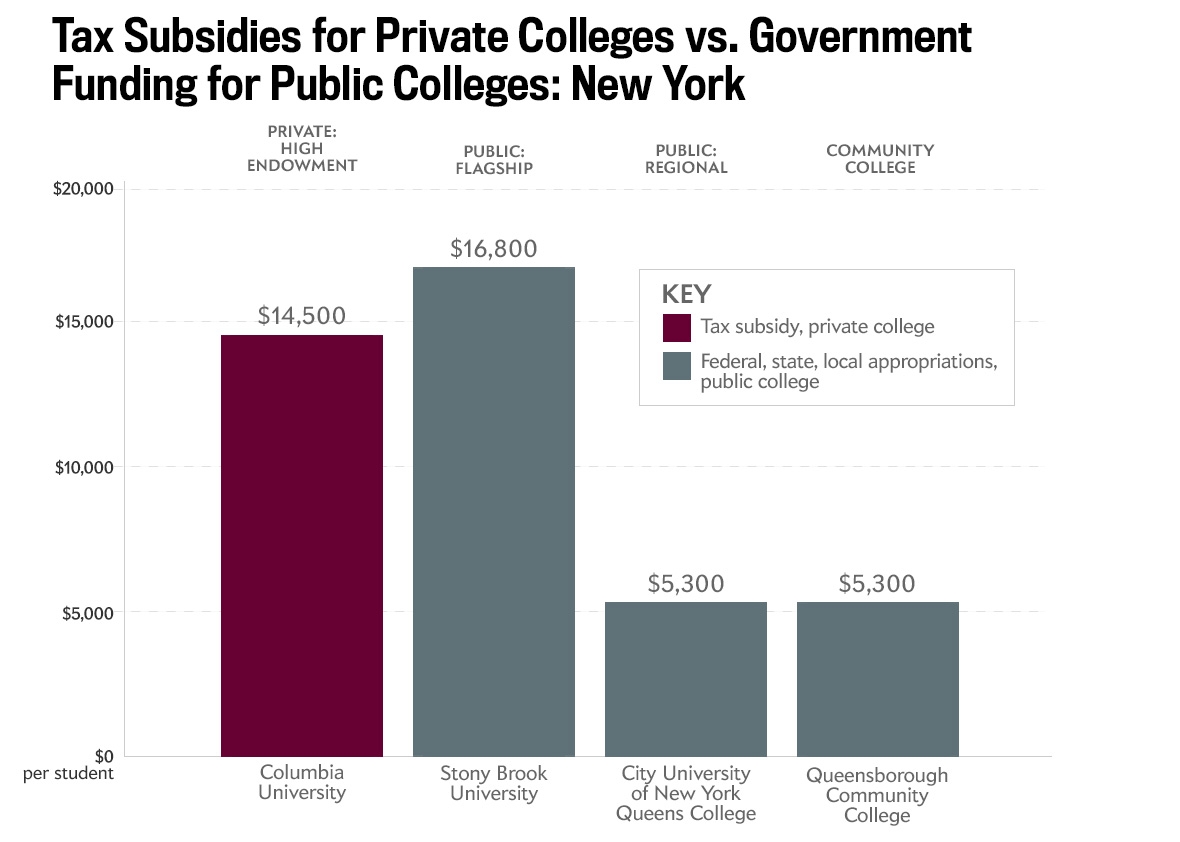

This isn’t a new idea by any stretch—in 2008, lawmakers in Massachusetts considered slapping a 2.5 percent tax on large university endowments—but Schneider has made an especially intriguing case for it. Earlier this year, he and Jorge Klor de Alva, a former president of the for-profit University of Phoenix, released a report that compared the approximate amount of money private colleges saved from not having to pay tax on their endowments with the funding state schools received from government appropriations. Though the authors were comparing different kinds of subsidies, the contrasts were nonetheless jarring. Princeton received $105,000 in tax benefits per student. Rutgers, New Jersey’s flagship public university, got just $12,300 per student in public funding. Whereas Harvard netted $48,000 per student in tax benefits, the University of Massachusetts–Amherst got a measly $9,900 in government backing. Among the 60 schools Schneider and Klor de Alva analyzed, private universities with large endowments averaged $41,000 in tax subsidies, compared with $15,300 in direct funding for public flagships, $6,700 for regional state colleges, and $5,100 for community colleges.

Chart by Slate

In short they showed the extent to which some very rich colleges are getting richer thanks to tax benefits most Americans scarcely think about when we consider the resources devoted to higher education in this country. “It wasn’t until we started calculating these numbers that we realized how big the discrepancies were between these private universities and the schools that were going to be educating most of the workers of the future,” Schneider says. “It’s a web of hidden subsidies that need to be talked about and investigated so we can figure out whether this is a socially desirable system.”

I want to be upfront: There are some aspects of Schneider and Klor de Alva’s report that should make watchers of this debate uncomfortable, issues that Politico and the Washington Post glossed over in their own coverage of the study. Take its source. The paper was published by the Nexus Research and Policy Center, which Klor de Alva runs and which was founded with money from the University of Phoenix’s parent company. In the past Nexus has produced dubious research boosting for-profit schools (which are notorious for predatory business practices) that made similar points about the subsidies received by wealthy, traditional colleges. There are obvious reasons to be skeptical about a report by a think tank associated with for-profit colleges claiming that nonprofit schools are leaching on the system. That said, Schneider, a former commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, is a generally respected figure in higher education policy associated with the center right. (Disclosure: Slate is owned by Graham Holdings Company, which also owns Kaplan, itself a big player in for-profit higher education.)

More substantively, Schneider and Klor de Alva’s report probably exaggerates the overall subsidy gap between elite private and state colleges to a degree. For instance, it doesn’t count the tax savings that some large state institutions enjoy on their own endowments—the University of Texas at Austin, for instance, is part of a nine-school system with a $25.4 billion endowment, while Rutgers has more than $900 million to its name. The study also doesn’t consider subsidies from the federal Pell grant program, which mostly benefit lower- and middle-income students at public institutions. And, perhaps most importantly, it probably overstates how much money colleges are saving thanks to their nonprofit status each year, because it treats all increases in the value of their endowments as taxable income, whether or not they were actually realized. In the real world, the government only taxes capital gains when investors sell their assets.

Chart by Slate

In other ways, though, the study may actually undercount subsidies to wealthy colleges. For one, it doesn’t take into account the more than $6 billion that Washington is expected to lose each year by making donations to educational institutions tax-deductible. Sadly, charitable giving is skewed toward a small percentage of already well-to-do schools and often leads to taxpayers footing part of the bill for extravagant gestures of ambiguous social utility, such as hedge funder Stephen Schwarzman’s $150 million gift to Yale, which will pay for a new student center with Schwarzman’s name on it.

Chart by Slate

In the end, it’s hard to say precisely what a perfect accounting of all the various subsidies schools receive would look like. Ideally, I’d love to see a researcher without Nexus’ baggage take on the subject. But even if the comparisons in Schneider and Klor de Alva’s report aren’t airtight, they’re in keeping with what we know about the massive inequalities in higher education. Private colleges and universities are sitting on hundreds of billions of dollars in their endowments. But that wealth, along with the sizable tax subsidies that help it stack up, is concentrated in the hands of a tiny few. In a world where the government only provides limited resources for higher education, we’re almost certainly shoveling an outsized share of them to schools that don’t need the financial help.

Of course wealthy universities see things quite differently. They tend to point out that although $36 billion or $21 billion might sound like a princely sum, much of that money is restricted to specific uses by donors. (If a railroad magnate in 1878 endowed a classics professorship, then the school needs to keep spending the returns on his money on Latin instructors, not a new biology lab.) Moreover, they note, the money needs to grow at a regular rate to make sure they can keep up with the fast-rising cost of running the equivalent of whole towns while offering generous financial aid and ensuring that professors can keep conducting cutting-edge research, from now until forevermore.

And some of these are fair points. Their extraordinary resources really have made America’s elite colleges the world’s envy, allowing them to bring together some of the most brilliant minds from here and abroad to crank out all sorts of wonderful innovations.

Still, that doesn’t change the fact that we seem to have stumbled into a system that disproportionately subsidizes the educations of a tiny few. So what, exactly, should we do about it?

Some critics of large endowments have argued that schools should simply be forced to spend more of their money hoard. In 2008, another time when elite schools were prospering and tuition was rising, Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley caused a minor uproar in higher education circles by proposing that colleges should be forced to spend 5 percent of their endowments every year, the same way private charitable foundations are. Recently, Victor Fleischer, a law professor at the University of San Diego, caused a similar stir with a New York Times op-ed demanding that schools spend 8 percent per year.

But it’s not clear what exactly that approach would achieve. Maybe schools would bolster financial aid and start paying adjunct faculty a living wage. Maybe they’d devote more money to renovating dorms or building lazy rivers in their student rec centers. At the end of the day, we’d still be heavily subsidizing wealthy schools, which would have to spend a bit more lavishly, but not necessarily more productively.

That’s what makes taxation more appealing. Schneider and Klor de Alva, for their part, propose a progressive tax on private college endowments worth more than $500 million equal to 0.5 to 2 percent of their total value. By their calculations, that would raise about $5 billion per year, which could be spent supporting cash-strapped community colleges. About 95 schools would be affected—with institutions like Harvard and Yale at the high end, and ones like Marquette and Villanova at the low end—and they would be allowed to cut their tax bills by deducting dollars spent toward financial aid.

Chart by Slate

Some might object to the idea of taxing a few colleges to fund others. And, to be sure, it’d be nice if we could simply pay for higher education in this country with a tax on Wall Street trading, as Bernie Sanders would have it. But progressives have lots of spending they would like to do, and there are only so many new taxes Washington will ever pass. Redistributing resources within higher education might not just be fair, but also necessary if we want to find ways to fund our public institutions.

Chart by Slate

A tax like Schneider’s would still raise other philosophical and logistical questions. For starters, why tax giant endowments at colleges but not other nonprofits? The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York commands a roughly $3 billion endowment—it’s hard to think of a coherent reason why it should escape the Internal Revenue Service if, say, Fordham University in the Bronx (endowment: $675 million) can’t.

Another quandary: Today, the government generally doesn’t tax savings. It taxes income. So why take a cut of wealth from colleges when we don’t do it to individuals? As Kim Rueben, a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, put it to me, “We’re going to tax Harvard, but we’re not going to tax Warren Buffet?”

And, of course, there might be unintended consequences. Even with write-offs for financial aid, taxing endowments could encourage schools to spend less on things society generally likes, such as new research labs. The government could tax schools and require them to spend a minimum amount, which is how it treats private foundations. But then you have to consider to what creative lengths Harvard might go to avoid the IRS.

Cutting down the tax advantages of rich schools, obviously, would not be simple. But it still worth seriously considering the idea. Maybe we should consider taxing the Met as well. Maybe the government could stick to what it knows and tax Harvard’s capital gains instead of its whole endowment. Maybe we could learn to live with a little tax avoidance. However we choose to do it, I think we’d all like to spend a little less money sending other people’s kids to Harvard.