The Year in Uber

The world’s brashest startup spent 2014 expanding aggressively and infuriating just about everyone.

Pablo Blazquez Dominguez / Getty Images; Eric Piermont / AFP / Getty Images

In June, as protests against Uber caused traffic to snarl roads in major cities across Europe, I wrote in Slate that there had “never been a better moment to describe Uber as ‘disruptive.’ ” In the months that followed, Uber has repeatedly attempted to prove that statement wrong.

When was Uber the most disruptive this year? Maybe when the employees of the on-demand car service ordered and canceled thousands of rides from its main competitor, Lyft, as part of a plan codenamed “Operation SLOG.” Or when a senior executive suggested conducting opposition research on journalists. Or when, around the same time, it came out that certain Uber employees had access to a “God View” tool that let them track the real-time location and movements of Uber riders without their permission. Or when the Central Business District of Sydney found itself waiting out a hostage crisis, and Uber chose to quadruple its fares there.

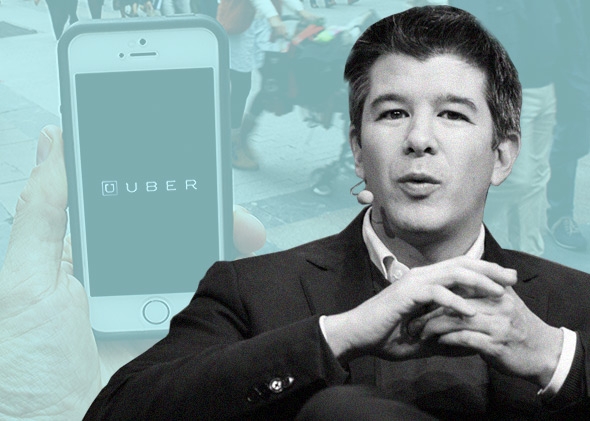

By now, you might be sick of Uber stories. I wouldn’t fault you for that. But as much as tech and business reporters have given their readers Uber fatigue this year, the company matters. Uber and its peers—Lyft, Gett, Sidecar, and others—are attempting to fundamentally change transportation by replacing taxis and maybe even car ownership. The vision of Travis Kalanick, Uber’s colorful and often audacious CEO, goes even further. He sees Uber as the forerunner of a comprehensive on-demand economy, one in which the push of a smartphone button triggers the almost instantaneous arrival of any physical thing. “If we can get you a car in five minutes,” he has said, “we can get you anything in five minutes.” In 2014, Uber didn’t inch so much as leap and bound toward that goal.

And so the most disruptive thing about Uber in 2014 may not have been a single moment, but rather the sum of all its aggressive and rapid forays. Over the last 12 months, the company has expanded from 66 to 266 cities, and from 29 to 53 countries. It serviced 140 million rides and racked up a staggering $3 billion in new funding for a valuation that tops $40 billion. Even in Silicon Valley, where investors treat million-dollar investments like pocket change, that’s a mind-boggling sum.

Of course, Uber, more than most tech startups, is in the business of being disruptive, an ethos that might help explain both its successful growth and its embarrassing stumbles. The company is brash and ambitious, even in the face of regulatory confrontations and bitter criticism. For better and for worse, 2014 was Uber’s biggest year to date, so charting all of its milestones and controversies of the last 12 months is practically impossible. (I didn’t even get to its kitten deliveries.) That said, here are the big ones:

The Year in Valuations

The rumors began to swirl in May: Uber was looking to join the 11-digit club. From Uber’s vantage point at the time—it had $258 million in funding for a $3.5 billion valuation—a financing round of that size would have been huge. At the least, it would have nearly tripled Uber’s estimated worth and put it alongside Airbnb and Dropbox in an elite group of $10 billion-plus startups.

It turned out the size of Uber’s new financing was even more staggering than anticipated: a $1.2 billion round of venture capital announced in early June that valued Uber’s business at $17 billion. Was Uber worth that much? In 2014, it was the funding deal that launched a thousand think pieces. Skeptics said the valuation was overblown; Uber’s operations were dangerous and illegal, liable to be shut down at a moment’s notice. Optimists saw Uber as a worthy challenger to taxi stalwarts, with the most starry-eyed praising its potential to replace car ownership entirely. At any rate, it’s safe to say the scale of the funding shook even Silicon Valley. Uber was suddenly worth almost as much as Hertz Global Holdings and Avis Budget Group, two rental-car giants, combined.

Over the summer, Uber took a few steps toward that ultimate dream of replacing taxis and owned cars with low-cost, accessible transportation, and toward becoming a comprehensive delivery company. In many regions, including New York City, it slashed fares by 20 percent to make them cheaper than local taxis. Around that time, Uber also began experimenting with logistical operations. In Manhattan, it introduced a messenger service called UberRush; “Corner Store,” an on-demand delivery service for everyday essentials in Washington, D.C., and UberFresh, a food delivery service with a rotating menu, followed. And in August, Uber rolled out UberPool, a carpooling option that facilitated supercheap pickups for people traveling similar routes. Uber’s main competition, Lyft, also introduced a carpooling service around that time.

But as the year wound down, Uber looked to have a solid edge on its competition. By one measure, as of September Uber was facilitating seven times as many rides as Lyft and adding more customers, more rides, and more revenue in absolute terms. Uber was operating in more than 250 cities and more than 50 countries, while Lyft was running in closer to 60 cities and had no international presence. In terms of funding, it also was hardly a contest: Uber had raised $1.5 billion and Lyft $332.5 million. And then in December, Uber made another announcement: It had raised an additional $1.2 billion for a new, astonishing valuation of $40 billion. For Uber, the year in financing was a rich one.

The Year in Regulatory Battles

The hallmark of Uber’s year may have been its willingness to defy local regulators as it marched into new cities and countries. The age-old taxi industry is a powerful one and doesn’t take kindly to new entrants—which is partly why Uber, so far, has embraced an expand-now, negotiate-later approach. In April, Belgium imposed a ban on Uber’s peer-to-peer ride service, UberPop. In June, the company’s unflinching advance brought major cities in Europe to a standstill as tens of thousands of taxi drivers gathered to protest Uber and the governments they felt had failed to regulate it. In July, Seoul declared Uber illegal under South Korean law, and in September, Germany implemented a nationwide ban on UberPop. By the time December rolled around, Uber was facing new lawsuits in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Portland, Oregon; it had been banned in Spain, Thailand, and New Delhi. In other cities, like San Antonio, local officials were considering regulations that Uber considered hostile to its operations.

Yet for all the controversy Uber has faced, it’s also remained remarkably unscathed. Shortly after surviving the massive spate of protests in Europe, Uber received a green light to operate in London on the technicality that its smartphone app could not be considered a taximeter “within the meaning of the legislation.” After Germany moved to ban Uber, the company boasted of huge spikes in sign-ups across the country; two weeks later, the ban was overturned by a German court. Most recently, Seoul followed up on its earlier attempts to halt Uber and charged Kalanick with violating local licensing laws. Uber, in typical fashion, has continued to operate there anyway.

The logic behind Uber’s brash and borderline-reckless strategy seems to be something like this: People need to try Uber to realize they want Uber—and once they do, it’s a lot easier for the company to rally support for its services. Uber has readily admitted that it’s not just growing a business but also running a massive political campaign. As its service gets bigger, the bet that consumer demand will outweigh local regulatory angst has gotten progressively safer. Over the course of the year, its petitions in support of “ride-sharing” have garnered some 500,000 signatures. And at last count, 18 jurisdictions in the U.S. have taken up “permanent regulatory frameworks for ridesharing.” With $3.3 billion in funding under Uber’s belt, those campaigns are set to continue apace in 2015.

The Year in P.R. Blunders

If regulatory battles were the defining feature of Uber’s year, public-relations mishaps were its defining blemish. The headaches began back in January when Uber’s New York City employees were caught ordering and canceling at least 100 rides from Gett, a competing ride service. A few months later, Lyft reported similar attacks: Uber contractors, it said, had ordered and canceled thousands of its rides in New York over the course of a month. Leaked internal documents obtained by the Verge showed that Uber’s New York team had carried out the cancelations as part of a larger plan they’d named “Operation SLOG.” Other incidents popped up elsewhere in the U.S.: a manager in Albuquerque who deactivated an UberX driver for tweeting a link to critical news coverage; a team in San Diego that attempted to keep new drivers off the road on Valentine’s Day to artificially push surge pricing higher. Most recently, Uber came under fire for implementing surge pricing in Sydney’s central business district as a hostage crisis played out.

Then there was Uber’s relationship with its drivers. Throughout its 5-year history, Uber has trumpeted itself as a heroic disruptor of the taxi industry—the company that could finally make providing rides a sustainable and profitable endeavor. Uber doesn’t call its drivers workers or employees; it calls them partners and “small business entrepreneurs.” In late May, Uber decided to prove this in style, and announced on its blog that the median annual income of an UberX driver in New York City had surpassed $90,000. On closer inspection, though, the math simply didn’t add up. To date, Uber hasn’t been able to produce the name of a single driver in New York City who’s earning that much. In early December, new data from the company showed that most full-time drivers on Uber’s New York City platform were earning $50,000 to $70,000—not bad money, but certainly not $90,000. For part-timers, the earnings were much more scattered. The marketing didn’t live up to the reality.

Of all Uber’s scandals and missteps in 2014, though, the most egregious by far came from Emil Michael, a senior company executive. In mid-November, BuzzFeed editor-in-chief Ben Smith reported that, at a recent dinner in Manhattan, Michael had suggested spending $1 million to hire opposition researchers who would dig up dirt on critical journalists. At the same time, Smith revealed that Josh Mohrer, the general manager of Uber in New York City, had on multiple occasions accessed the personal ride data of a BuzzFeed reporter without obtaining her permission. The media firestorm was instantaneous, and a half-hearted, 14-tweet apology from Kalanick did little to quell it. The great irony was that the P.R. implosion came just as Uber had apparently resolved to soften its image; the dinner Smith attended was one of several such recent overtures to the media. Something didn’t add up there. It seemed that despite its bro-ish, somewhat libertarian reputation, malice wasn’t what had gotten the better of Uber so much as ineptitude. The company might want to add a stay at charm school to its list of 2015 goals.

Then again, that list is probably long enough already.