Bombs Away

-

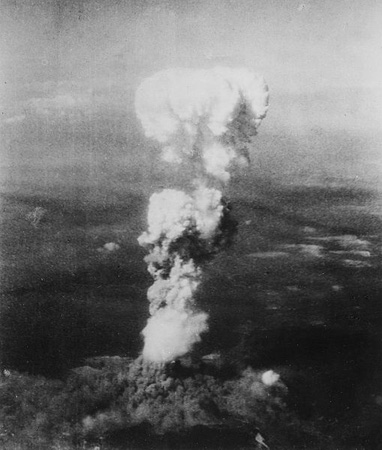

Photograph of Hiroshima blast by Sgt. George R. Caron, August 6, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Hiroshima blast by Sgt. George R. Caron, August 6, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.Hiroshima, Aug. 6, 1945

“I saw a single enemy airplane flying over Hiroshima,” an observer watching 2½ miles from the city recalled after the war. “It dropped or fired a brilliant object. I thought at first that it was an incendiary bomb, but then I saw what looked like a smoke ring from a funnel, gradually falling toward the ground. It grew larger almost immediately and increased in brilliance and soon covered an area almost as big as the city. A flame appeared which was even brighter than the sun. I thought I might get hurt so I fell flat on the ground.”

Two exhibitions in New York, “Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945,” a selection of cold, clinical pictures of the architectural devastation, at the International Center of Photography, and “The Atomic Explosion,” a festive array of pictures of atomic bomb explosions (mostly tests), at the Peter Blum Gallery in Soho, go hand in hand to suggest that the American development of the atomic bomb, though initially motivated by fear that the Nazis would make one first, had much more to do in the end with “pure and simple scientific curiosity.” It was, as one scientist put it, too “technically sweet” not to pursue.

Both shows, one cold, one hot, provide a visceral sense of how it was possible to block out the human implications of the bomb.

-

Photograph of Trinity site explosion by Berlyn Brixner, July 16, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Trinity site explosion by Berlyn Brixner, July 16, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.Trinity Site Explosion, July 16, 1945

After the Germans surrendered, the drive to build the atom bomb actually gained steam. The race was no longer with the Nazis but with the end of the war. As John W. Dower writes in the excellent catalogue “Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945,” the “machinery moved into high gear to ensure that the ‘gadget’ would be ready to use before hostilities against Japan had ended.” And once the bomb was made, there wasn’t much question that it would be used.

Why Hiroshima? It was a good clean test subject. It was more densely populated than New York City’s five boroughs, had had no prior damage, and offered a flat terrain for a 6,000-foot radius as well as a variety of buildings and bridges. It was “an ideal target for measuring the atomic bomb’s power and effectiveness.”

-

137 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima], October 31, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

137 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Group of people near damaged trolley cars, Hiroshima], October 31, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Damaged Trolley, Hiroshima, Oct. 31, 1945

And measure they did. A month after Hiroshima was bombed, a team of seven photographers employed by the Physical Damage Division (or PDD) of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey went to Hiroshima to document the devastation. Their aim was not just to see how the bomb had performed but to find out how the United States could protect itself from the kind of horror it had just dealt out.

The PDD created what Adam Harrison Levy, a documentary film producer and writer, describes as a “cold catalogue of destruction”—1,100 pictures of bombed, burned, and twisted buildings and bridges paired with bland captions and organized according to how far they were from Ground Zero. (The bomb actually detonated 1,900 feet above that point, at Air Zero.)

The exhibition at ICP, some 60 photos organized in one room by curator Erin Barnett, has the same cool, rational structure as the study on which it is based. It makes you look at Hiroshima the way the PDD photographers and government scientists must have seen it—at a remove, piece by piece, and totally disconnected from human reality.

-

253 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima], October 24, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

253 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Ruins of Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima], October 24, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Shima Surgical Hospital, Hiroshima, Oct. 24, 1945

The ICP photographs, which have been declassified for over 60 years, originally belonged to Robert L. Corsbie, one of the PDD photographers, who went on after the war to become a designer of bomb shelters. They’re hung within black concentric rings painted on the wall and labeled GZ 100, GZ 1000, GZ 1200, etc., radiating out from Ground Zero (a corner of the room), where there is, appropriately, no image at all. Descriptions of the damage, lifted from the government report, appear as captions.

The prose and the images are so clinical that the viewer, too, is put in a clinical state of mind. Most of the buildings near Ground Zero were simply flattened, the curator notes, because the force of the blast was almost all vertical there.

At 100 feet from Ground Zero, you can see the rubble of the Shima Surgical Hospital in the foreground. What lessons were learned? “Combustible debris completely burned.” In the background, the frame of the standing structure was deemed to be “cement mortar and well laid brick” and the workmanship “greater than comparable buildings in United States.”

-

1 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima], November 20, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

1 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Distorted steel-frame structure of Odamasa Store, Hiroshima], November 20, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Odamasa Store, Hiroshima, Nov. 20, 1945

These documents of the ruins are so flat and affectless that it’s hard not to try to relate them to other, less calculated kinds of destruction and other more poetic ruins—in Italy, England, and the United States. I found myself giving the pictures my own captions. Hurricane. Tornado. Colosseum. Forum. Perhaps it was a way to make them more humane. Or less human.

These ruins, I told myself, look just like devastation caused by time and nature. And the further I was from Ground Zero, the easier this was to do. At GZ1100, the ruins of the Odamasa Store reminded me of the ruins of the New York World’s Fair.

-

257 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Ruins of Nagarekawa Church of the Japan Christian Society interior, Hiroshima], October 26, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

257 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Ruins of Nagarekawa Church of the Japan Christian Society interior, Hiroshima], October 26, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Nagarekawa Church, Hiroshima, Oct. 26, 1945

At 3,000 feet from Ground Zero, the inside of the Nagarekawa Church of the Japan Christian Society resembled the ruins of an old English Abbey in Shropshire.

-

6 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Remains of a school building], November 17, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

6 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Remains of a school building], November 17, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.School Building, Nov. 17, 1945

From a mile away and further, Hiroshima’s ruins began to look like those caused by natural disasters—floods, tornados, and hurricanes. Perhaps this is because the blast at this point exerted more of a horizontal force than a vertical one, just like a storm.

-

9 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Buckle of north wall of wing number one of Funairi Grammar School, Hiroshima], November 20, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

9 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Buckle of north wall of wing number one of Funairi Grammar School, Hiroshima], November 20, 1945. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Funairi Grammar School, Hiroshima, Nov. 20, 1945

Some 8,000 feet away from Ground Zero, the damage to the Funairi Grammar School looked like a hotel in the South Pacific damaged by a hurricane.

-

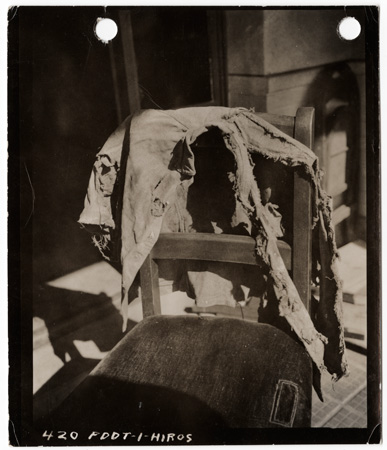

5 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Charred boy’s jacket found near Hiroshima City Hall], November 5, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

5 CREDIT: United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Physical Damage Division [Charred boy’s jacket found near Hiroshima City Hall], November 5, 1945. Gelatin silver contact print. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Boy’s Jacket, Nov. 5, 1945

There aren’t many people shown in these pictures because that was beyond the mission of the PDD survey and because some of the photographers who did manage to document radiation’s effect on people—bleeding gums, hair falling out, bluish spots on the skin, rotting flesh, death—had their film censored or confiscated.

Death isn’t altogether absent, though. This photo, taken 3,300 feet from Ground Zero, has the following caption: “Showing charring or burning of a coat of a boy who was in the open near the City Hall.” What was learned from remains like these? White clothes, apparently, can survive an atomic bomb; black ones will incinerate. And the boy in the jacket? He didn’t make the caption.

-

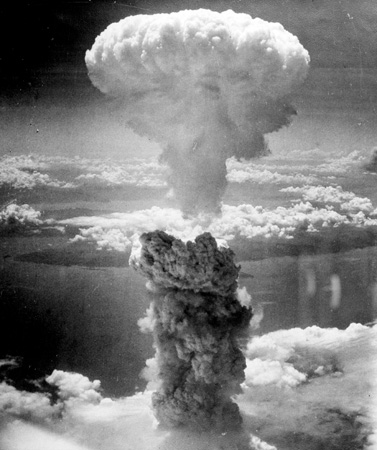

Photograph of Atomic bombing of Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Atomic bombing of Nagasaki, August 9, 1945. Photograph from Wikimedia Commons.Bombing of Nagasaki, Aug. 9, 1945

After “Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945,” it is both a shock and a relief to look at the exuberant photographs of exploding atom bombs and mushroom clouds taken during and after the war, at Alamogordo, Nagasaki, Bikini Atoll, and various Nevada test sites. “The Atomic Explosion: A Collection of Vintage Photographs” is as festive and hot as the ICP show is dark and cold. (Because the Peter Blum Gallery declined to supply the necessary permissions for its images, all photographs of the nuclear blasts here, which are quite similar to ones at the gallery, are public domain pictures found on the Internet.)

-

Photograph of Baker test explosion by United States Department of Defense, July 25, 1946 via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Baker test explosion by United States Department of Defense, July 25, 1946 via Wikimedia Commons.Baker Test Explosion, July 25, 1946

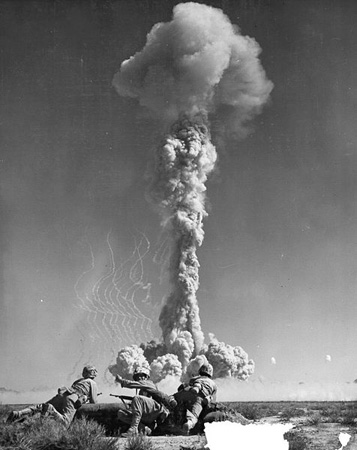

These thrilling blast photographs—there is no other word for them—go a long way toward showing the fascination of atomic bomb explosions, which went on for decades after the war was over. Some of the mushroom clouds look like exclamation marks. Others look cozy and solid enough to inhabit. And some of the pictures include white rocket streamers, which were sent up while the bombs went off to measure how air currents would be affected. These lend the proceedings a party atmosphere.

-

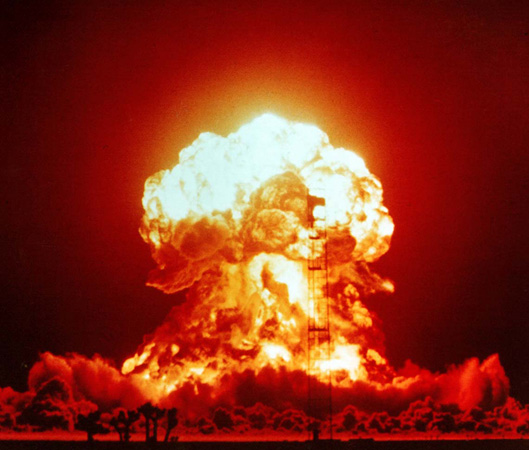

Photograph of Badger test explosion, April 18, 1953 via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Badger test explosion, April 18, 1953 via Wikimedia Commons.Badger Test Explosion, April 18, 1953

Every bomb blast has its own crazy personality. Some look like party hats. Some have faces. Some have two faces. Some have bodies. You can see why the Japanese artist Takashi Murakami got the idea of creating a character out of a mushroom cloud.

Just as I had found myself thinking of picturesque ruins at the ICP exhibition, so I found myself calling up famous paintings and movie scenes while looking at the pictures of the blasts, rather than imagining how much tragedy might be stuffed into each one of those happy clouds. To see them as animate is to forget their deadliness.There are Fragonard’s delicate colors, I said to myself. There is Goya’s Colossus. And here, poof, is the great and wonderful Oz!

CREDIT:

-

Photograph of Tumbler-Snapper test explosion by the federal government of the United States, May 1, 1952 via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Tumbler-Snapper test explosion by the federal government of the United States, May 1, 1952 via Wikimedia Commons.Tumbler-Snapper Test Explosion, May 1, 1952

Mushroom clouds are so photogenic that it’s easy to overlook the human creatures watching them, destroyed by them, and, of course, photographing them. Some observers wear sunglasses. Some have taken off their glasses. Some look bored. Some have hands on their hips, in a proprietary way. Some are kneeling. Some are close. Too close? -

CREDIT: Unidentified Photographer, [Mushroom cloud from atomic bomb test, Yucca Flat, Nevada], April 22, 1952. Courtesy International Center of Photography.

CREDIT: Unidentified Photographer, [Mushroom cloud from atomic bomb test, Yucca Flat, Nevada], April 22, 1952. Courtesy International Center of Photography.Atomic test, Yucca Flat, April 22, 1952

After the war, a fourth-grade student who survived the attack on Hiroshima asked this question: “Those scientists who invented the atomic bomb—what did they think would happen if they dropped it?" Dower offers a chilling answer: “they did not think much about this until the project neared completion.”

Yet surely they knew. As Levy writes, Masao Tsuzuki, Japan’s leading radiation expert, studied the effects of radioactivity on rabbits at the University of Pennsylvania in 1926 and found that it caused “the oozing of blood through pores and hemorrhaging.”

After the war, Tsuzuki met the physicist Philip Morrison, slapped him on the knee and said: “Ah, but the Americans—they are wonderful. It has remained for them to conduct the human experiment.”

Also in Slate, postcards from the age of atomic tourism.