Postcards From Camp

Madonna fell, and I was there to catch her.

Contrary to the bad reputation it’s received over the years, camp is not malicious. But the zealotry with which it attaches itself to certain figures—particularly “tragic” women—can come off that way, especially when a person’s entire career or public image becomes synonymous with camp seemingly by force. There is an important difference between a tackle and hug, however, and no discussion of camp would be complete without an accounting for its peculiar style of embrace.

Indeed, embrace may not even be quite the right word. Camp’s approach to its loved ones is more like the proper way of greeting a drag queen: one kiss per cheek, but only in the air. Engendered in this kind of kiss is a practical respect for the queen’s artistry—you don’t want to muss up the makeup. But read another way, the air kiss reveals a shared understanding that drag performance—like all performances, including celebrity and even life in general—is always precarious, always at risk of ruin at the hands (or mouth) of some brutish external force. The inch or two of space between blush and lips is an acknowledgement that the nuances of beauty are fleeting enough already; let’s not touch while we can still admire from afar.

So, when a camp icon is on top—as Jessica Lange or Lady Gaga are at present—camp tends to keep a safe distance, relishing the surreptitious moments of insider pleasure that the star provides while tolerating alternative noncamp appreciations (i.e., good television actress or fun pop star). But camp is at its most admirable when things aren’t going so well. When the star falters, when the career begins to decline, that’s when camp’s understanding of the precariousness of performance becomes most important. That’s when its muted, private pride transforms into an intense, cradling empathy. Camp gravitates toward “The Fall” not out of cruelty, but of compassion.

The fall, I should mention, can come in a variety of forms. Some are literal, like when Madonna awkwardly lost her footing due to a star-crossed pairing of high heels and bleachers at the 2012 Super Bowl halftime show (her own rendition of the “Glenn Close shuffle”).

To be sure, Madonna has for decades been in a highly self-aware dialog with campiness, but I would argue that the Super Bowl fall, occurring as it did amid a fantastically brazen argument for mainstream pop relevance against the likes of Gaga, Nicki Minaj, and Beyonce, marked a pivot. As I watched her stiff, aged (if defiantly well-toned) legs give out for that split second at the center of the American cultural universe, my attitude toward Madonna shifted; once a nexus of transgressive camp pride, she suddenly seemed frail, in need of protection. The nuances in her persona that interested me were no longer about power and subversiveness; they have been replaced by her errors, her imperfections. Madonna fell, and camp was there to catch her.

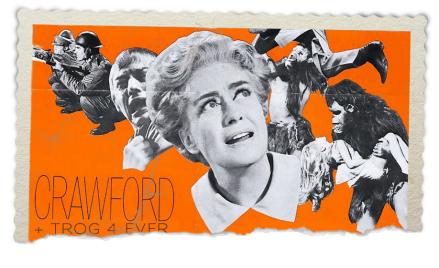

Of course, the most notable camp catch of all time was Joan Crawford. According to feminist scholar Pamela Robertson, Crawford’s mainstream appeal was already in decline after Mildred Pierce (1945) and certainly by Johnny Guitar (1954) due to her age and unwillingness to take on a softer, more Marilyn Monroe–like self-presentation, which was increasingly popular with audiences. However, during the same period, Crawford’s status as perhaps the most important camp icon of all time was well on its way toward being cemented. Most fans will point to her lurid 1962 duet with Bette Davis, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, as the moment of coronation, but I prefer Trog (1970), Crawford’s final film, in which she plays a hard-nosed primatologist intent on protecting a half-man, half-ape creature she believes to be the Missing Link. The debased transcendence of the famous actress mincing across Trog’s Styrofoam-crafted subterranean lair in a cream, bell-bottomed pantsuit or enthusiastically presenting colored flash cards to the beast in an attempt to get him to speak endears Crawford to me forever. I feel for her in that moment not because she’s great, but because she’s abject—and in some ways, so am I.

Trog still courtesy of Warner Bros.

It’s a shame that camp’s penchant for empathy has long been misinterpreted as exploitation. There’s a nasty, pervasive rumor in circulation that camp sullies the mainstream careers of stars like Madonna and Crawford, type-casting them forever as the embodiments of cheap jokes. But when these people fall, they become trash to mainstream audiences—camp is waiting to prize them as treasure. As gay studies scholar David Halperin notes, camp takes “ … an exhilaration in identifying with the lowest of the low.” Camp practitioners are not merely “tender,” as Sontag put it, toward the fallen; rather, they feel an intense affiliation with them, perhaps because they are often gay and understand how hard it can be to keep up appearances. From Crawford’s decline to Madonna’s misstep, from Tammy Faye Baker’s mascara-stained cheeks to The Queen of Versailles’ financial delusions, camp sorts through the cultural junkyard like an abjection magnet, seizing upon discarded-but-still-glittering bits of debris.