Andy’s Acolytes

A new exhibition shows that Warhol’s imitators can’t compete with the real thing.

“Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years,” open through the end of the year at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, is a revelatory show, but not for the reasons the curators intended.

Judged in terms of what they set out to do, which was to demonstrate how Andy Warhol has transformed art in the half-century since he first made his mark (and the quarter-century since he died), it’s a failure, and a drab one at that.

The show juxtaposes 45 works by Warhol with 100 works by 60 other artists who were influenced by him in some way. But what’s striking about the mesh is how unimaginative and mediocre most of his successors are compared with the real thing. Or, to put it another way, the show underscores how brilliant Andy Warhol was compared with his so-called followers.

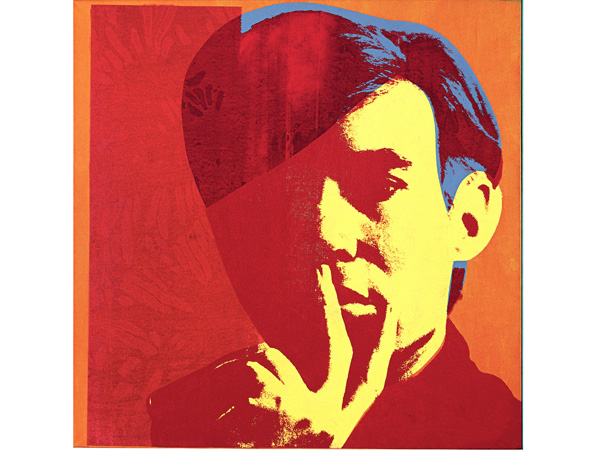

Viewed alongside other artists of his era in most museum collections, Warhol seems deadpan, ironic, a bit fey. But viewed alongside most of the artists arrayed around him at the Met show, his work hums, sometimes bursts, with intensity, passion, even (a phrase rarely associated with Warhol) emotional commitment.

Warhol emerged as a serious player in the art world in 1962, as one of several New York painters—most notably, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and James Rosenquist—who rebelled against the Abstract Expressionists and sought to create a new kind of American art that incorporated the artifacts of everyday life, even popular culture. Warhol was the late-comer in the group and arguably the least talented as a craftsman; yet it’s Warhol who made the deepest impression, whose style and works—the silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s soup cans, Brillo boxes, and car crashes—are most widely recognized, even by people who know little else about art.

The critic-philosopher Arthur Danto goes so far as to call the era of the early ’60s and beyond “the age of Warhol,” because Warhol recognized—and expressed through his art—that modern Americans view and interpret reality not so much through direct experience as through commercial images (TV, tabloids, comic books, advertising) and celebrity.

A turning point in Warhol’s development occurred in 1961, when he painted a Coca-Cola bottle in two styles: the first, laced with the Abstract Expressionist drippings that were de rigueur in its day; the second, straight, no drippings. He went with the second, and thus was Warhol Art born: an art that simply declared, as Danto summarized, “Paint what we are” and whose breakthrough “was the insight into what we are,” namely, “the kind of people that are looking for the kind of happiness advertisements promise us that we can have, easily, and cheaply.”

Some critics, including the authors of the Met show’s catalogue, depict Warhol as a “dark social critic” of American life, but this is off the mark. Before Warhol became a rich and famous artist, he was a rich and famous graphic designer; his ad campaign for I. Miller shoes won a coveted industry prize. Even after he became a much-lauded museum artist, he kept doing commercial work, too, most notably for record-album covers. One hallmark of his art, in fact, is its obliteration of the boundaries between high and low, culture and commerce, art and life.

And everything about Warhol’s life and art suggests that he loved the American artifacts that he transformed into icons. There’s an eye-opening moment in Ric Burns’ 2006 PBS documentary Andy Warhol when the camera pans across the gold-and-glitter interior of the church where Warhol worshipped as a sickly boy in Pittsburgh—then cuts to a shot of Warhol’s famous gold silkscreen painting of Marilyn Monroe.

There, in one jump cut, lies the real story: The subjects of Warhol’s art are the saints and goddesses of his personal church, his psychic iconography. He liked Campbell’s soup, he worshipped Marilyn Monroe, he was fascinated by headlines of destruction and death. To the extent that his art is darkly critical of American society, it’s because it reflects our own predilection for these same things. It truly reflects our obsessions because Warhol is one of us: He’s not ironically commenting on the mass culture of celebrity, tabloid disaster, or processed food; he’s reveling in it.

You have to go downtown to the Museum of Modern Art to see Gold Marilyn Monroe (MoMA wasn’t about to lend out one of its mainstay attractions), but the Met show does include Turquoise Marilyn, one of several smaller Monroe portraits that Warhol made in the first few years after her death in 1962. It’s a ghostly painting; the bright colors make her look like a strumpet, but the colors aren’t garish; in fact, they’re pretty. We’re attracted to it, and that attraction is what makes the painting disturbing, haunting—yet without diminishing its decorativeness: quite a feat to pull off.

In a similar vein, take a long look at Orange Disaster #5, a large canvas that consists of 15 identical silkscreen images (taken from a newspaper photograph) of the electric chair at Sing Sing prison, each image painted bright orange. Over the years, Warhol made lots of electric-chair paintings, as well as a series of 10 limited-edition prints, but this one (lent by the Guggenheim Museum) is the one that sends chills. Repetition is a frequent Warhol device, a graphic display of the mechanized commercialization of culture; but here, it also suggests the endless repetition of death-penalty executions. And the neon sign flashing “Silence,” barely visible in the upper right hand corner, underscores the invisibility of these chamber killings, the inaudible pain, the absence of protest—just as the lovely orange swaths turn the painting (at a fleeting glance) into an attractive abstraction and (at a longer, second glance) an attraction that’s not so abstract: a reflection of the pleasure that we take, at some level, with viewing the instruments of violence and death.

Even a simpler screenprint, Cagney—based on a still from Public Enemy, showing James Cagney, his shadow against a wall, and another shadow of someone holding a machine gun about to do him in)—captures, in its rough edges, the raw energy of the actor and the movie, of the whole gangster-celebrity culture: not to condemn it—Warhol clearly finds it cool, too—but simply to present it and to let the social critique (if you want to draw one) drift through its afterglow.

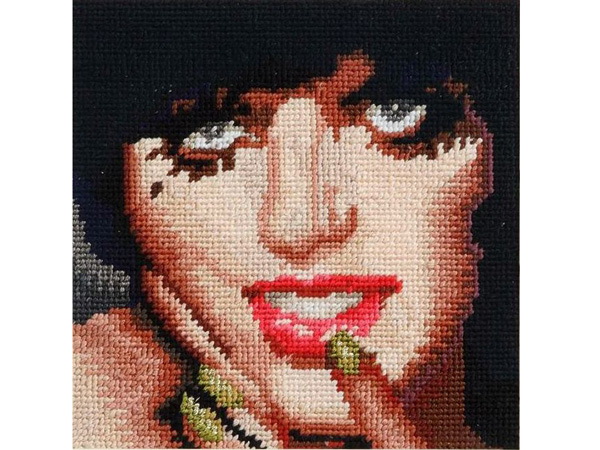

Compare these spectacles of drama and tension with the works around them. Francesco Vezzoli’s cotton embroidery of Liza Minnelli is vulgar and off-putting; it says nothing about her or the celebrity machine surrounding her. Alex Katz’s painting of Lita Hornick is flat and drab, her expression vacuous (and not in any “social commentary” way). Jeff Koons’ ceramic sculpture of Michael Jackson and his chimp Bubbles is flamboyant dime-store kitsch. Christopher Wool’s repetitive pattern on aluminum is a yawn. In all these cases, we’re seeing the difference between an artist who’s invested in his subjects, who (regardless of how glitzy they might be) is probing for their essence—and craftsmen who are messing around, who think it’s enough of a “statement” to skate and doodle on the surface.

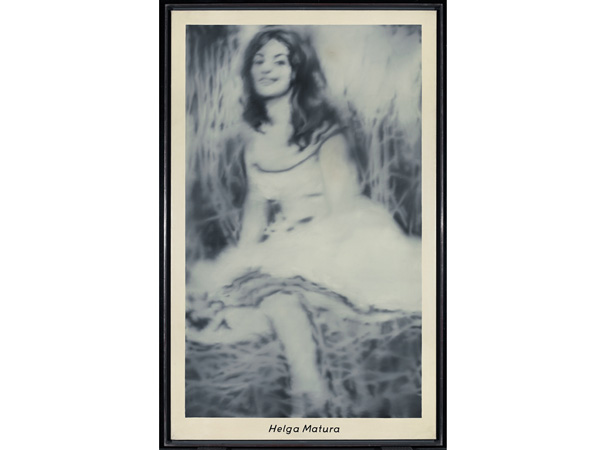

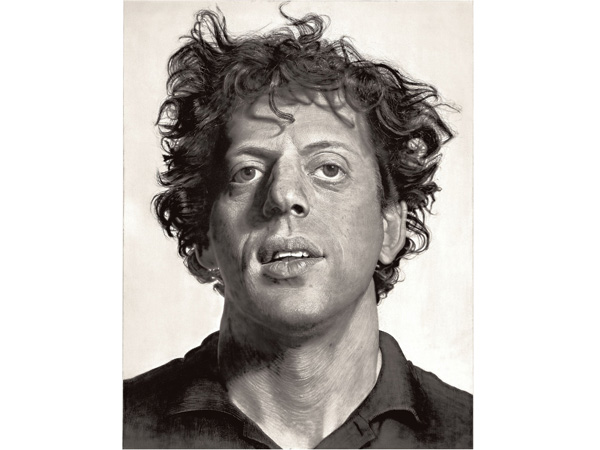

There are exceptions. Gerhard Richter’s oil paintings, especially Helga Matura and Evelyn (Blue), have the dreamlike haze of a gnawing memory. Cindy Sherman’s photographed portrait of herself as Marilyn Monroe exudes both innocence and desperation: a worthy sequel to Warhol’s Marilyn prints. Edward Ruscha’s Burning Gas Station is a painting of true wit, mixing minimalist abstraction, movie-poster starkness, and Pop Art banality, only to set the whole combine in flames. Chuck Close’s 9-foot-tall portrait of a tousle-haired Philip Glass, though painted in the most mechanical way imaginable, as a series of matrix-grids, nonetheless captures the subject’s creative spirit with amazing zest.

These artists stand out because they took Warhol’s breakthrough premise—that things like Coke bottles, celebrities, cow heads, and gas stations are subjects worthy of art—and launched their own trajectories, fueled by their own distinctive visions: like Warhol himself. The Met show could have used more of them.