Close Your Ears!

The new radio horror proves that listening to a gory scene can be more terrifying than watching it.

In retrospect, the most remarkable thing about Orson Welles’ radio broadcast of War of the Worlds in 1938 wasn’t the mass hysteria and panic it caused, but the fact that anyone cared about a radio drama in the first place. These days, radio drama is as dead as disco, kept on life support mostly by the BBC. But it shouldn’t be this way. Sound has a way of slithering into our ears and burrowing deep down into the folds and wrinkles of our brains in ways that sight does not.

Seeing is believing, the saying goes, but hearing is far less certain. Sight is public, social, and definite. Sound is spectral, uncertain, and psychological. In the last century, part of radio’s promise was to expand the borders of communication, perhaps even beyond life itself. Nikola Tesla believed he was receiving radio messages from other planets, Thomas Edison believed that Tesla might have the technology to communicate with the dead, and Marconi, a pioneer in long-distance radio transmission, claimed that he received Morse code from Mars. From Upton Sinclair’s ESP experiments, published under the title Mental Radio, to Friedrich Jürgenson’s electro-voice phenomena (EVP), which now provides the soundtrack to every ghost hunting show on cable, sound has always had a strong grip on our subconscious.

Radio drama was the medium of the masses in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, but TV and movies rendered radio drama pretty much dead by 1960, and by the ’90s radio itself wasn’t feeling too good. But with podcasts and audiobooks surging in popularity as more people don earbuds and spend more time in their cars, the radio drama should be primed for a comeback. Except it’s not happening. The image of the traditional radio drama is one held over from the ’30s: attenuated organ music, tinny sound effects, and actors speaking in a kind of non-naturalistic sportscaster’s voice (“It’s a bear! Look out! He’s coming right at you and—what’s that?—he has a gun!”). They’re as comfortably old-fashioned as your grandfather’s cardigans, but they shouldn’t be.

Headphones short-circuit your mind by destroying your sense of sound localization. Suddenly you’re hearing wind and rain but looking at a sunny city street. You hear a horse, but it’s coming from inside your ears. Your thoughts are suddenly isolated in an imaginary space. This would seem to be a field ripe for exploitation by artists with an urge to experiment, and while there are some, most of the people making radio dramas today are enthusiastic amateurs, reproducing yesterday’s sound.

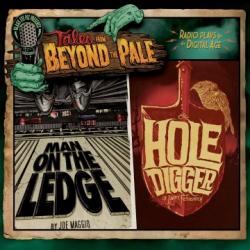

Someone needs to give a bunch of professionals a shot at radio drama, and it’s no great surprise that that person turned out to be Larry Fessenden. A New York City based horror film director, Fessenden owns Glass Eye Pix which has produced almost all of the pivotal movies from the new wave of young horror directors: Ti West’s House of the Devil, Jim Mickle’s Stake Land, and James Felix McKenney’s Automatons among many others. Fessenden, hearing an old Boris Karloff radio drama while driving one day, spoke with his collaborator, Glenn McQuaid, and decided that producing a series of horror radio dramas would play to their tastes for low budgets and retro style. Actors like Ron Perlman and Vincent D’Onofrio were paired with low-budget horror directors like J.T. Petty and Simon Rumley and the anthology series, Tales From Beyond the Pale, was born.

Just released as a five-CD set containing all 10 episodes, Tales from Beyond the Pale looks backward into nostalgia while offering glimpses of futuristic ambition. Some of the episodes are content to ape old-fashioned radio dramas, only with better production values and more cussing, offering fun twists and turns on a narrative level, but staying literal-minded in terms of sound design: Doors open and close, footsteps are created by a recording engineer with a shoe on each hand, and actors describe sea monsters that viewers can’t see for themselves. They’re a lot of fun and offer a kick of straight nostalgia, especially in the case of “This Oracle Moon” by Jeff Buhler (writer of The Midnight Meat Train) and featuring Ron Perlman (Hellboy) and Doug Jones (the faun from Pan’s Labyrinth). Its cannibal cavemen on the moon, insane androids, and grizzled spaceship captains are ripped right out of an old-school EC Comic.

Going retro has its charms, but a handful of these episodes push the state of the art to the next level. In Sarah Langan’s “Is This Seat Taken?” the old-fashioned declamatory style of line-readings is abandoned for a creepily intimate dialogue between two repressed psychopaths who meet cute on the Long Island Railroad. Him: “My parents thought I was too shy for college and that made it hard so I dropped out and the only job I could get was stringing telephone lines? Along the West Side Highway? I rode the train, like, ten times a week dressed as a construction worker, smelling terrible. It’s like something snapped and I started writing about shooting up all these people. You know, like the fancy people, with lucky lives? And friends? And inch-deep souls? I picked the 5:38 to Mineola and I even got the gun and bullets. And the morning I planned to do it I showered, shaved, brushed my hair and I slit my wrists. My parents found me.” The actors wisely underplay their lines and it sounds so natural that the unfolding drama sucks you in the way eavesdropping on the subway does.

Paul Solet’s “The Conformation” makes use of the fact that while we can close our eyes, it’s impossible to close our ears. Early radio drama was so suggestively gruesome that public outcry caused the National Association of Broadcasters to meet in 1947 and banish horror programming to late-night slots and to ban completely auditory depictions of gory murders, the beating of children, and police brutality. Solet’s piece, about an obsessed plastic surgeon and his best patient, features scenes of surgery that manage to create, solely with terse dialogue and sound effects, the most graphic mental images of the year, Human Centipede 2 be damned. Be warned, the following clip of their first surgery together is not for the weak.

Sound designer, Graham Reznick, recruits horror icon, Angus Scrimm (now 85 years old and with a voice like caramel-coated gravel) to appear in “The Grandfather”—which is about an old man whose daughter and son-in-law may or may not be putting him in a nursing home. His world starts to fall apart when they inform him that they’re having his grandson, Kevin, “put down” because his childhood hasn’t “worked out.”

Creating 3-D space with sound, the actors sound like they’re sitting inside your skull and you find your eyes tracking their invisible movements as they speak. The narrative is intentionally fragmented, and there’s something spookily disorienting and uncomfortably intimate about the way it sounds. Reznick has discovered that radio works best when it’s just a voice, playing to us alone, in the dark. And, inside our heads, we’re always alone, and it’s always dark.