The Many Faces of Helen

How to find an actress who can launch a thousand ships.

-

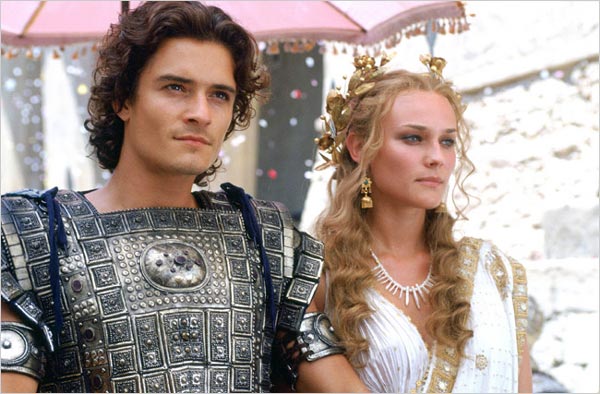

Diane Kruger as Helen in Troy (2004) © Alex Bailey/Warner Bros. Entertainment.

Diane Kruger as Helen in Troy (2004) © Alex Bailey/Warner Bros. Entertainment.After months of searching for a worthy Helen, Troy's producers chose Diane Kruger, a relatively unknown German actress who is undeniably good-looking. But when you see her face in the trailer, or wheezing by on the side of a bus, the inevitable feeling is one of letdown. Kruger is blond and pretty, but unremarkable—she'd look at home in an ad for Herbal Essences shampoo. Her face, one suspects, could launch three ships, maybe four. (Some wag once coined a term for the amount of physical beauty it takes to launch one ship: a milliHelen.) Looking at Kruger it's hard not to think, They fought the Trojan War for this?

-

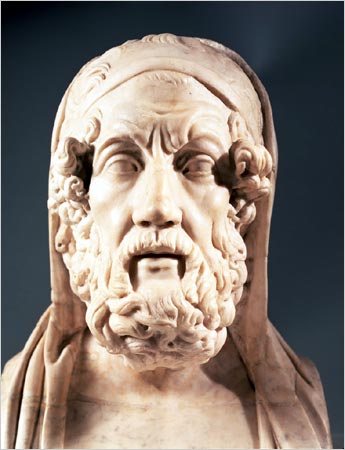

A bust of Homer © Archivo Iconografico, S.A./Corbis.

A bust of Homer © Archivo Iconografico, S.A./Corbis.The Iliad offers little help for casting directors. The Homeric text seldom describes what Helen looks like. (When it does, she's "white-armed" and garbed in "shimmering linen.") Instead, the poem attends closely to how men respond to her. When Helen first appears, the Trojan elders murmur: "No wonder the men of Troy and Argives under arms have suffered years of agony all for her, for such a woman. Beauty, terrible beauty! A deathless goddess—so she strikes our eyes!" A Greek man, listening to a bard sing these lines after dinner, was free to lean back and imagine his own version of extraordinary, unsettling beauty. Legend has it that Homer was blind, so sculptures of him tend to have an uncanny expression: It looks as though he, too, is picturing something unfathomable in his mind's eye.

-

A detail of a vase, or skyphos, that shows Helen's abduction and return © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A detail of a vase, or skyphos, that shows Helen's abduction and return © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.Ancient artists, of course, didn't have the luxury of being vague. This vase, painted by the artist Makron between 490 and 480 B.C., shows Helen's reunion with Menelaus after the war. In the image, Helen's seductive charms lie not in her dark hair or her stylized face, but in her body. Helen is the figure second from the left. She's holding open her cloak, revealing the transparent gown beneath, and you can see that she's not exactly wearing underwear. Menelaus, standing to her right, is taking note as well—follow the direction of his gaze.

This archaic game of peekaboo has roots in classical texts. In Euripides' Andromache one character scoffs at Menelaus: "Then Troy fell ... Helen was in hand, but still you didn't kill her. One look at her breasts, and you let go of your sword, kissing, lapping at that traitorous bitch."

-

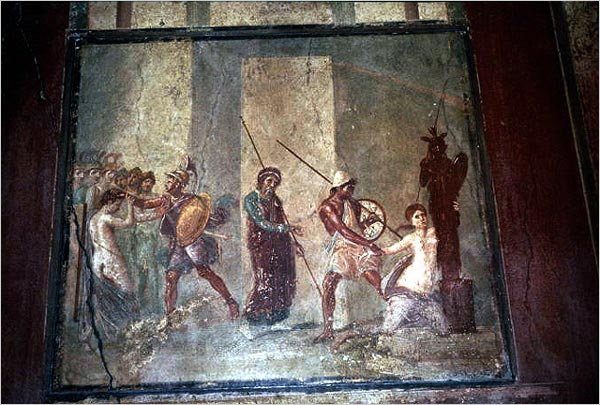

A wall-painting from the House of the Menander at Pompeii © Professor Ann O. Koloski-Ostrow, Brandeis University.

A wall-painting from the House of the Menander at Pompeii © Professor Ann O. Koloski-Ostrow, Brandeis University.

Five centuries later, the painter who decorated the walls of this house in Pompeii took cues from Makron and Homer. Helen is the woman at the left of the painting; Menelaus is once again struck dumb to her right. Nudity remains essential—Helen's cloak is even further off in this one, and she's certainly callipygian. But the painter conveys Helen's beauty primarily through the reactions of the men around her. We can't see Helen's features, just her back and a sliver of her face. Instead, we focus on Menelaus, who stands agape, and the phalanx of soldiers ogling Helen in the background.

Five centuries later, the painter who decorated the walls of this house in Pompeii took cues from Makron and Homer. Helen is the woman at the left of the painting; Menelaus is once again struck dumb to her right. Nudity remains essential—Helen's cloak is even further off in this one, and she's certainly callipygian. But the painter conveys Helen's beauty primarily through the reactions of the men around her. We can't see Helen's features, just her back and a sliver of her face. Instead, we focus on Menelaus, who stands agape, and the phalanx of soldiers ogling Helen in the background.

Five centuries later, the painter who decorated the walls of this house in Pompeii took cues from Makron and Homer. Helen is the woman at the left of the painting; Menelaus is once again struck dumb to her right. Nudity remains essential—Helen's cloak is even further off in this one, and she's certainly callipygian. But the painter conveys Helen's beauty primarily through the reactions of the men around her. We can't see Helen's features, just her back and a sliver of her face. Instead, we focus on Menelaus, who stands agape, and the phalanx of soldiers ogling Helen in the background. -

CREDIT: The Abduction of Helen, attributed to Zanobi Strozzi, © 2000 National Gallery

CREDIT: The Abduction of Helen, attributed to Zanobi Strozzi, © 2000 National GalleryBy the Renaissance, Helen had become a blond, which is how many people continue to think of her. In this octagonal panel—which would have been presented to a mother at the birth of her child—she also becomes a stiff, doll-like inanimate object, remarkably unfazed by getting a piggy-back ride from a man in red tights. The moment of Helen's departure for Troy is one that artists frequently choose to represent, perhaps because it affords great drama: The scene can be construed as the violent abduction of an innocent or as the skulking escape of guilty lovers. But for the Florentine artist Zanobi Strozzi—who's thought to have painted this work—it's an opportunity to lavish attention on Helen's decidedly 15th-century sleeves. Here, great beauty is conflated with great wealth: This Helen conforms to Renaissance notions of a pinup girl (blond hair, white skin, small breasts, small chin), but she's the most notable figure in the scene because she has the nicest clothes.

-

CREDIT: The Abduction of Helen (oil on canvas) by Luca Giordano (1632-1705) from Musee des Beaux-Arts, Caen, France/www.bridgeman.co.uk/Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library.

CREDIT: The Abduction of Helen (oil on canvas) by Luca Giordano (1632-1705) from Musee des Beaux-Arts, Caen, France/www.bridgeman.co.uk/Giraudon/Bridgeman Art Library.As artists became more concerned with naturalistic representation and their figures more closely approximated the postures and expressions of actual human beings, those who painted Helen had to decide what she really looked like. In 1680 Luca Giordano, a prolific Neapolitan painter known for his quick work, met this challenge with a degree of specificity and assurance not seen in earlier efforts. His contrarian strategy: to paint the most beautiful woman in the world by making her ugly.

Giordano's Helen—though sufficiently blond and alabaster of skin—is a sturdy girl. Her body is contorted and her nose looks red, as though she's been crying. (This is definitely an abduction.) But what's cunning about the composition is that Helen becomes beautiful because she wants you, the viewer. Giordano turns each of us into Menelaus.

-

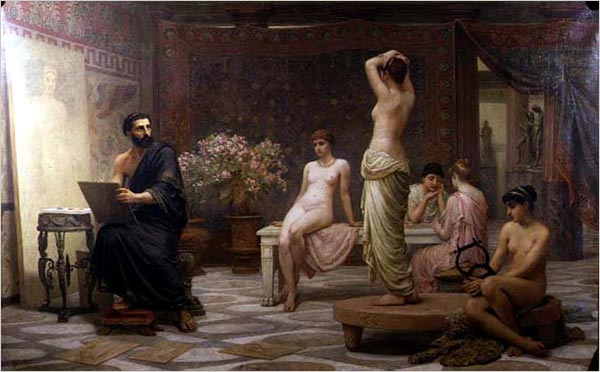

CREDIT: The Chosen Five of Crotona, 1885 by Edwin Longsden Long (1829-91) from Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth, U.K./www.bridgeman.co.uk. Not to be reproduced without permission.

CREDIT: The Chosen Five of Crotona, 1885 by Edwin Longsden Long (1829-91) from Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth, U.K./www.bridgeman.co.uk. Not to be reproduced without permission.Pliny the Elder was among the first to write about how hard it is to paint Helen. He told of a Greek artist, Zeuxis, who sought to paint Helen of Troy but couldn't find a woman beautiful enough to serve as his model. So he chose five village girls, each of whom had one perfect feature, and painted a Helen who had the eyes of one, the nose of another, and the mouth of a third.

Victorian artists were particularly taken with this tale, and it is a recurring motif in work of the era. The story dovetails nicely with the Victorian notion that true beauty existed not on this earth, in the bodies of mortal women, but in some idealized sphere that could be accessed only by visionary (and usually male) artists. Here, the painter Edwin Long doesn't bother to prove that he's capable of imagining and painting perfection. The portrait of Helen, at left, is half-finished. Instead, Long zeroes in on the five models, each a demure vision of Victorian womanhood. Even nude, they are marble-white and without makeup, with downcast eyes and their hair chastely coiled on their heads.

-

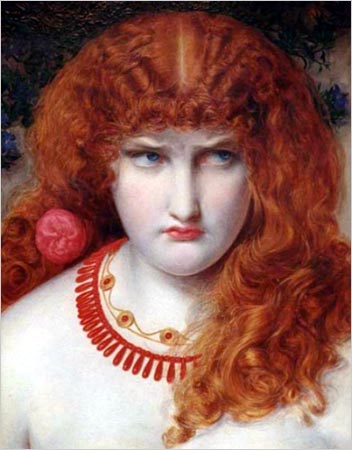

CREDIT: Helen of Troy, by Anthony Frederick Sandys courtesy of National Museums

CREDIT: Helen of Troy, by Anthony Frederick Sandys courtesy of National MuseumsThe Victorians were convinced that beauty is universal and ahistorical—that what Paris desired in ancient Sparta we would desire today. This may explain the confidence with which they set out to reproduce Helen: Anthony Frederick Sandys' version, painted in 1867, is fearlessly detailed. At the same time, of course, the Helens these artists envisioned are markedly Victorian. Sandys' Helen has a surly mien and all the characteristics of a Victorian femme fatale: red lips, rouged cheeks, and the loose tresses typically used to suggest a loose woman. For Sandys, Helen is a carnal figure, not entirely in control of her passions, her actions, or the consequences. This eroticized Helen may seem a surprising choice for such a prim era, but in some ways, it makes sense: Victorians idealized chaste women because they feared (and were fascinated by) the destructive power of those who weren't.

-

Rosanna Podestà as Helen and Jacques Sernas as Paris in CREDIT: Helen of Troy (1956) © Everett Collection.

Rosanna Podestà as Helen and Jacques Sernas as Paris in CREDIT: Helen of Troy (1956) © Everett Collection.Hollywood's first major effort to find a suitable Helen came in 1956, with Robert Wise's Helen of Troy. Wise chose an unknown Italian actress, Rosanna Podestà. The brunette played the role in a blond wig, and her lines were dubbed over in unaccented English. Neither the performance nor the film met with much critical acclaim. (Teenage boys, however, were enthralled, and some still write about their adolescent longings for the busty Podestà on IMDb.com.) In the role of Helen's handmaiden, Wise cast another European unknown, one who might rate several hundred milliHelens—Brigitte Bardot.

-

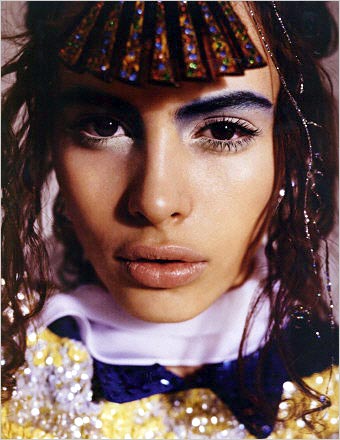

Elizabeth Taylor as Helen in CREDIT: Doctor Faustus (1967) © John Springer

Elizabeth Taylor as Helen in CREDIT: Doctor Faustus (1967) © John SpringerLucinda Syson, one of the casting directors for the upcoming Troy, told me they were searching for an actress with the epic beauty of, say, Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra. Most moviegoers will have forgotten that Taylor played Helen once, in the 1967 film Doctor Faustus, which starred Richard Burton in the title role. In Marlowe's play, Faustus sells his soul to the devil for 20-odd years of fun on earth, some of which involved consorting with "the admirablest lady that ever lived." In the film, Taylor's Helen is a silent and almost spectral presence. And the headdress—which seems fashioned out of Christmas ribbon—is more than a bit Medusa-esque.

-

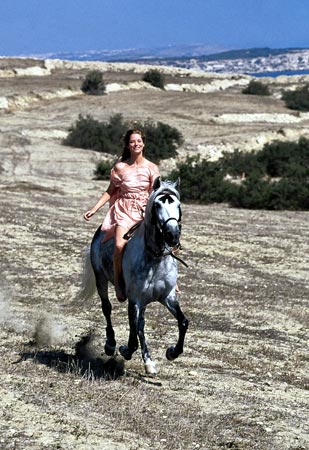

Sienna Guillory as Helen in CREDIT: Helen of Troy

Sienna Guillory as Helen in CREDIT: Helen of TroyModern retellings of the Trojan War have at least one thing in common—since abduction isn't an acceptable courtship tactic these days, they tend to paint the romance between Paris and Helen as a straight-up love story. This was true of Wise's epic, and it is true of Helen of Troy, a 2003 TV movie that starred Sienna Guillory. The director, John Kent Harrison, envisioned a very independent Helen: "I approached it by saying, What does beautiful mean in the context of a culture that is so rigidly conventional? I wanted someone alive and rebellious." Harrison's Helen enters the film at a gallop—she's riding a horse, bareback, wearing a flimsy gown. "When someone conventional like Paris sees that, he's going to go crazy," Harrison said. Although Harrison believed that modern viewers would be taken with his spirited Helen, his producers weren't so sure that her equestrian athleticism was sexy, and they asked him to shorten the scene.

-

Photo of Elite model Kemp Muhl by Jennifer Tzar.

Photo of Elite model Kemp Muhl by Jennifer Tzar.So how did Diane Kruger end up starring in a movie with Brad Pitt? The producers of Troy had fabulous resources and an enormous number of precedents to draw from, and they cast a wide net. Syson, the casting director, says they were looking for an unknown: "When you introduce a new face there's no associations—oh this girl was in this or that," Syson said on the phone from her office in London. "She is Helen of Troy." During her search, she took to combing lad mags and the fashion pages, and came across this woman, a model named Kemp Muhl who now works with Tommy Hilfiger. Syson tracked Muhl down and had her read for the part, only to learn that Muhl was 16—too young to play a woman who's been in Troy for a decade.

-

Photograph of Natalie Imbruglia © Axel/Zuma Press; Photograph of Laetitia

Photograph of Natalie Imbruglia © Axel/Zuma Press; Photograph of LaetitiaThe search was global, with actresses from Croatia, New Zealand, Australia, and Argentina in the running. Syson wouldn't reveal the names of the Italian actresses they considered (if the men of Slate had their way, Monica Bellucci would have been a finalist) but in the end, accents were a concern. "You can't-a have-a Helen talking like-a this," Syson said on the phone. (Her inflection brought to mind Rocco DiSpirito's mom.)

Countless armchair casting directors suggested Laetitia Casta, the Victoria's Secret model for whom the word "languorous" seems to have been invented. "We did pursue Laetitia Casta," Syson said. "But someone on her staff wasn't taking us very seriously." Casta never read for the part, so she was ruled out. Syson's brother, whose judgment she has trusted ever since he insisted she cast the then-unknown Catherine Zeta-Jones in Entrapment, was sure that the pop singer Natalie Imbruglia was perfect for the part. Zeta-Jones, incidentally, was never considered: Orlando Bloom had already been cast as Paris, and she was deemed too old to play his consort. -

Diane Kruger as Helen and Orlando Bloom as Paris in CREDIT: Troy (2004) © Alex Bailey/Warner Bros. Entertainment.

Diane Kruger as Helen and Orlando Bloom as Paris in CREDIT: Troy (2004) © Alex Bailey/Warner Bros. Entertainment.In the end, the producers chose Kruger. "She had a sensuality that wasn't too over the top," Syson said. "She had a beautiful stillness—a softness, but also a hardness. There's something modern and old."

To my eyes, Kruger is a bit too modern (even though the director did ask her to pack on a few pounds, the better to approximate the fuller figures of yore). But that is the crux of the Helen question: Can the Helen on the vase—or the canvas, or the screen—live up to the Helen in your head?

When you think about it, the notion of Helen is really something like the concept of infinity. She's every beautiful woman you've ever seen, only immeasurably more so. When I picture her, she's a bit blurry around the edges: I leave room for Helen to possess a loveliness beyond what I can imagine. And it's that sense—the sense that Helen's beauty is somehow beyond our ken—that makes the power she wields convincing. So if someone gave me the chance to know what Helen really looked like, I might be tempted, but I'd courteously decline.