Star Wars Is a Postmodern Masterpiece

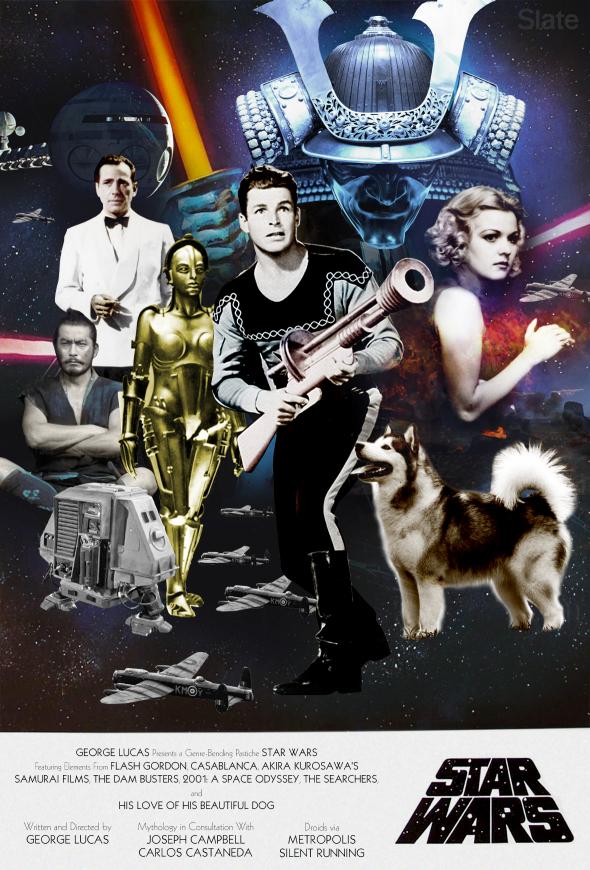

How George Lucas spliced together Westerns, jidaigeki, space adventure serials, fairy tales, dogfighting movies, and Casablanca to create Hollywood’s first world-conquering collage.

There are few faster ways to incense a movie geek than by calling Star Wars “sci-fi.” Star Wars may feature spaceships and aliens, but (pushes glasses up) its aspirations are definitely not those of science fiction. Ask what Star Wars actually is, however, and you’ll receive as many answers as there are scoundrels at the Mos Eisley Cantina. Star Wars is a Western. Star Wars is a samurai movie. Star Wars is a space opera. Star Wars is a war film. Star Wars is a fairy tale.

A Jedi craves not such narrow interpretations. In fact, Star Wars—the original 1977 film that started it all—is all these things. It’s a pastiche, as mashed-up and hyper-referential as any movie from Quentin Tarantino. It takes the blasters of Flash Gordon and puts them in the low-slung holsters of John Ford’s gunslingers. It takes Kurosawa’s samurai masters and sends them to Rick’s Café Américain from Casablanca. It takes the plot of The Hidden Fortress, pours it into Joseph Campbell’s mythological mold, and tops it all off with the climax from The Dam Busters. Blending the high with the low, all while wearing its influences on its sleeve, Star Wars is pretty much the epitome of a postmodernist film.

This can be easy to overlook nowadays, when new entries in the ever-expanding Star Wars universe are largely self-referential, elaborating on their own mythology, repeating old in-jokes, holding up Vader’s mask like an ancient relic. Viewed this way, the original Star Wars seems notable mostly as the foundation upon which an empire has been built—the sequels and prequels, the heavily indebted franchises, indeed the whole blockbuster economy. The movies are dead, we’re told, and Star Wars shot first.

It’s undoubtedly the case that Star Wars changed the movie industry. But it also changed the cinema arts, in ways that are now as forgotten as old Ben Kenobi at the outset of Episode IV. You probably no longer think to ask why a Jedi is called a Jedi, why they dress in samurai robes, or why the preamble that opens each movie scrolls the way it does, receding slowly into the distance.

To answer those questions, we’ll need to imagine our way back to a galaxy, far, far away, when George Lucas was an artsy film student and budding bricoleur. By retracing the steps of his hero’s journey, from a farm town to blowing up the Death Star, we can unlearn what we have learned and see anew the power of Star Wars.

A Long Time Ago …

Animation of scenes from Star Wars and Flash Gordon via “Star Flash Gordon Wars”/YouTube

“I don’t think I’ve ever come across anyone so immersed in film. I have an idea he goes to bed in it, wrapped up in it, you know, the actual material.”

— Alec Guinness on George Lucas

Bricoleur might sound like a heady term for the creator of Jar Jar Binks. These days, whenever Lucas talks about how he’s abandoning big Hollywood to make “experimental films,” people laugh. (He’s been saying this for decades, with nothing but the Star Wars prequels and 2012’s Red Tails to show for it.) But as a film student in the 1960s he was a prodigy, and he got his start with abstract, often collagelike shorts.

Lucas became fascinated with non-narrative films as a teenager. Regularly making the hour-plus drive from his hometown of Modesto, California, to San Francisco, he immersed himself in the avant-garde film scene there, attending the Canyon Cinema screenings of filmmaker Bruce Baillie—which began when Baillie started projecting avant-garde shorts onto a bedsheet in his backyard—along with those of the French New Wave films of directors like Jean-Luc Godard. At the University of Southern California, where he was part of the first generation of filmmakers that would emerge from film school, he was movie mad, watching as many as five movies a weekend. Perhaps no movie had as great an influence on him as Arthur Lipsett’s 21-87. A tone poem about the relationship between man and machine made from throwaway news clips and out-of-context sounds, the movie blew Lucas away. He projected it over and over again—“twenty or thirty times,” he recalled.

The movie showed Lucas that filmmaking could be an act of collage, with the editor as auteur. His first proper film at USC was Look at Life (1965), a one-minute short that spliced together images from Life magazine to express his burgeoning hippie consciousness, as photos of counterculture and authority figures act out a battle between love and oppression. Lucas recalled that the movie won “twenty or twenty-five” prizes at film festivals across the country and “changed the whole animation department” at USC.

Lucas became convinced that editing was just as central to filmmaking as writing and filming, and as an homage to Lipsett, he featured the number 2187 in just about everything he directed. (In Star Wars, Leia is held in Cell 2187.) By far his most ambitious student film was Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB (1967), a 15-minute sci-fi short that, like 21-87, mused on the relationship between humans and technology. Opening with a disorienting montage comprised of surveillance footage from the dystopian future (it’s set in 2187), and eventually taking the more familiar pop form of a chase sequence, it won first prize at 1968’s National Student Film Festival and inspired Hollywood producers like Universal’s Ned Tanen to sit up and say, “Who the hell did this?”

Lucas would never master snappy dialogue (“You can type this shit, George,” Harrison Ford famously complained on set, “but you sure can’t say it!”) or directing actors (Lucas later recalled, “I manage ‘action’ and ‘cut’ and ‘faster’ and ‘more intense,’ and then, uh, mostly I sit there looking miserable and quiet”). But he was always comfortable in the editing room. “George makes his visuals come to life with montage,” Steven Spielberg explained in the early ’80s. “That makes him unique in our generation, since most of us do it instead with composition and camera placement.” In the room where he wrote Star Wars, Lucas sat under a big photo of Sergei Eisenstein, the pioneer of montage.

Adventures on the Planet Mongo

“Star Wars is built on top of many things that came before. This film is a compilation of all those dreams, using them as a history to create a new dream.”

— George Lucas, 1975

We owe the existence of Star Wars to Federico Fellini. After the feature version of THX 1138 received a muted response from critics and the marketplace in 1971, Lucas wanted to make a film that would show that he wasn’t so soulless and robotic as the inhabitants of that movie’s fictional future. He developed a paean to the nights he spent racing up and down Modesto’s main strip, in the more innocent years before the Vietnam War. But he also tried to purchase the film rights to Alex Raymond’s books about Flash Gordon, the hero of the space adventure serials that Lucas loved as an 11-year-old. They weren’t available—luckily for us, they had already been optioned by Fellini, the auteur behind La Dolce Vita and 8½.

Disappointed, Lucas turned to American Graffiti first, which would become one of the biggest hits of 1973, and one of the most profitable movies of all time, earning back its budget more than 150 times over. It also earned critical raves and a nomination for Best Picture, making Lucas the hottest new director in the industry. He used his newfound leverage to make his adventure in space.

Though it was no longer an official adaptation of Flash Gordon, Star Wars kept many of its trappings. This is apparent right from Star Wars’ famous opening scroll, which borrows from the preambles that opened each chapter of the Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers movie serials. Lucas fell in love with the old 1930s film serials in the ’50s, when they were broadcast every night on KRON-TV, the only channel available to him as a boy in Modesto.

The elements that Lucas borrowed from Gordon and Rogers are almost too numerous to count. There’s the style of editing—both Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers used a variety of old-fashioned wipes to move quickly between action scenes. A number of characters and locations are lifted straight out of the old serials and their spinoffs. As Lucas biographer Dale Pollock has noted, the Flash Gordon book The Lion Men of Mongo includes a C-3PO–like “five-foot-tall metal man of dusky copper color who is a trained servant and speaks in polite phrases.”

As pointed out by the site Kitbashed, one of the most exhaustive attempts to chronicle Star Wars’ origins, the most likely inspiration for Princess Leia’s famous earmuff hairdo are the braids of Flash Gordon’s Queen Fria.

Image by Slate, stills from Flash Gordon via Universal Pictures, Star Wars via Lucasfilm

His devotion to the style of the old serials even had Star Wars ending with a cliff-hanging teaser as late into the process as his second-draft screenplay (then titled Adventures of the Starkiller):

The Starkiller would once again spark fear in the hearts of the Sith knights, but not before his sons were put to many tests … the most daring of which was the kidnapping of the Lars family, and the perilous search for:

“The Princess of Ondos.”

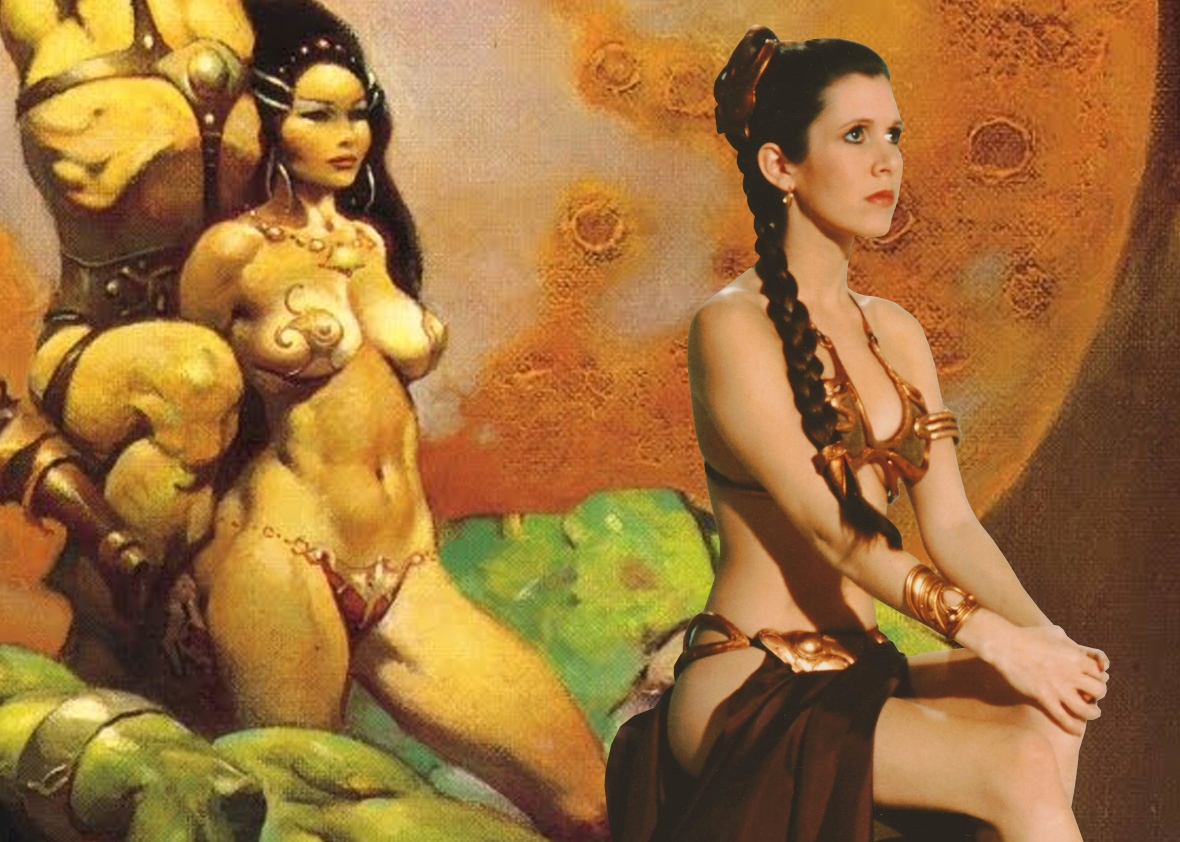

Of course, Lucas also drew from other space adventures. Especially influential were Frank Herbert’s 1965 book Dune and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter of Mars books, which Lucas specifically name-checked alongside Flash Gordon in his 1975 story summary for Fox executives. Many of Star Wars’ names seem to come straight from John Carter: Burroughs’ series included beasts called banths (similar to Star Wars’ banthas) and large predatory insects called sith. The costume designer for Return of the Jedi has also said that Princess Leia’s famous bikini was imagined as a throwback to the skimpy metal outfits worn by Dejah Thoris, Burroughs’ titular Princess of Mars.

Image by Slate, source images via Frank Frazetta, Lucasfilm

Others have pointed out that Burroughs’ Mars books include royalty called jeddaks and jeddaras, names that might sound familiar. Lucas likely had another inspiration in mind, however, when he named his soon to be famous knights.

The Return of the Jidaigeki

“Your sad devotion to that ancient religion has not … given you clairvoyance enough to find the Rebel’s hidden fortr—”

— Admiral Motti, just before he’s Force-choked by Darth Vader

In The Making of Star Wars, Lucas says that when he first began writing the screenplay, around the turn of 1973, “the film was a good concept in search of a story.” He knew he was making an adventure serial in space. But what was his plot? That’s when he thought of 1958’s The Hidden Fortress, which he’d recently rewatched. By the time he’d completed his 10-page handwritten treatment The Star Wars in May, it followed the Akira Kurosawa movie almost beat for beat.

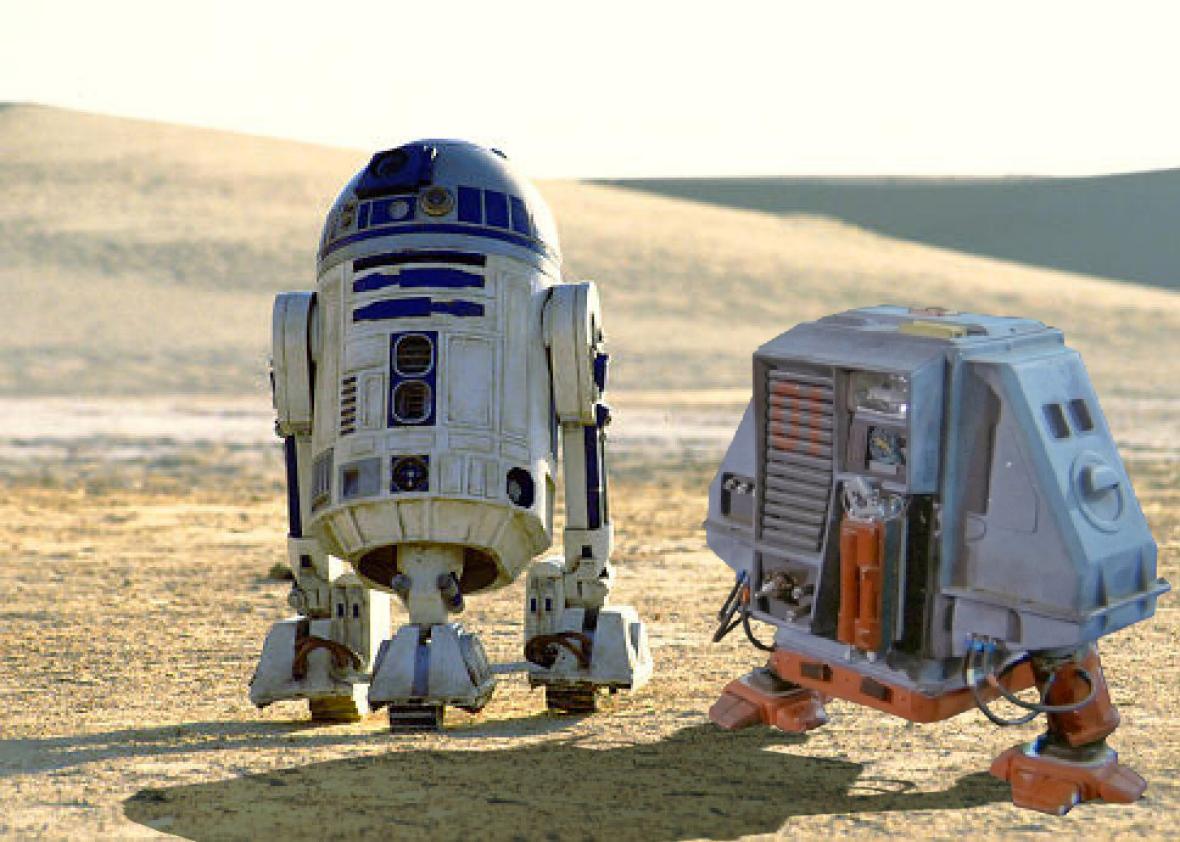

The Hidden Fortress was one of the legendary Japanese director’s jidaigeki, or “period dramas,” and it follows two peasants in the midst of a war between two clans. The peasants escort an undercover princess as well as precious cargo. (In Hidden Fortress, as in Lucas’ original treatment, it’s a pile of treasure instead of the plans for the Death Star.) Lucas’ later first draft hewed closely to this structure. Lucas especially liked the way “the story’s point of view was told from the lowest-level person in the film” and in a note for the second draft he wrote to himself, “Whole film must be told from robots’ point of view.” He even considered casting Kurosawa’s greatest star, Toshiro Mifune, who plays a general in Hidden Fortress, as former general Obi-Wan Kenobi. While most explicit mentions of the rebels’ “hidden fortress” ended up on the cutting room floor, there remains a moment in which Admiral Motti begins to form the words—until Vader interrupts him.

Lucas also drew heavily from Kurosawa’s other samurai jidaigeki. As many others have pointed out, Luke and Obi-Wan’s encounter in the Mos Eisley Cantina seems to be modeled on a similar sequence in 1961’s Yojimbo, in which Mifune’s samurai chops off the arm of an aggressive, trash-talking challenger. (“I’m a wanted fugitive,” warns one of the baddies in Yojimbo. “We’re wanted men. I have a death sentence on 12 systems,” boasts the pig-nosed ruffian in Star Wars.)

I could go on. Star Wars concept illustrator Ralph McQuarrie described Lucas’ vision for Vader’s mask as a “helmet like a Japanese medieval warrior.” Many have suggested that a shot in Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala that shows a sunset at the same time as a moonrise could have been the inspiration for the famous binary sunset in Star Wars. Kurosawa’s movies, like the old serials, were noted for using old-fashioned wipes. As for the lightsaber, Lucas contends the idea was his own, but the prototype, like his film, was assembled from cinematic scrap: the hilt was fashioned from an old photographic flash unit, and the sound was made by combining the buzz of a TV with the hum of an old USC movie projector.

Cowboys and Aliens

“You step into all this weirdness and you find that the scene that you’re doing is similar to scenes you’ve seen before in other movies that you can imagine very easily. There is a scene that’s based on a kind of Western concept. Shooting the guy under the table. There was no mystery to it. It was just a different face on something that was quite familiar.”

— Harrison Ford in 2004

Kurosawa’s movies were highly influenced by Westerns, so it’s no surprise that Lucas incorporated his own mashed-up take on the gunslinger archetype in the form of Han Solo, who wears leather riding boots and holsters his laser blaster low on his hip like a cowboy. When he draws first to shoot Greedo under the table, it resembles a nearly identical sequence from Sergio Leone’s 1966 spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly:

Animation via “Everything Is a Remix Part 2”/Vimeo

Known for his referential takes on Hollywood Westerns (the first of which was based on Yojimbo), Leone was called “the first postmodernist film director” by cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard. The sequence Lucas admired from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly might have itself been borrowed from John Ford’s 1964 Western Cheyenne Autumn.

According to The Making of Star Wars, Leone’s 1968 Once Upon a Time in the West was one of the movies Lucas screened for his crew to illustrate the look he wanted. Vader’s iconic entrance in Star Wars parallels the entrance of Frank (Henry Fonda) in Once Upon a Time in the West, with both men emerging through smoke into the wreckage of a massacre they’ve just ordered. Once you’re paying attention, the Western touches are everywhere. If you listen closely to Boba Fett’s movements, you can hear that sound designer Ben Burtt added the jingle of spurs.

Perhaps the clearest bit of cutting-and-pasting from Westerns is the sequence when Luke discovers the murder of Owen and Beru Lars, his uncle and aunt. This is straight out of the famous sequence in Ford’s 1956 masterpiece The Searchers, in which Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) is lured away in search of the cattle stolen from his brother’s neighbor (also named Lars), only to return to find his brother’s family has been massacred.

Animation via “Star Wars: Kitbashed”/Vimeo

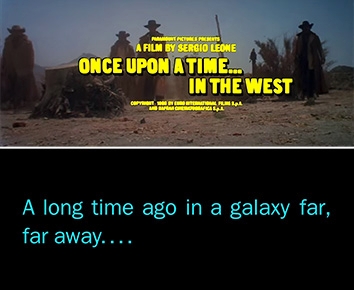

The Jedi With a Thousand Faces

“I put this little thing on it: ‘A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, an incredible adventure took place.’ Basically it’s a fairy tale now.”

— George Lucas, December 1975

Image by Slate, stills of Once Upon a Time in the West via Paramount, and Star Wars via Lucasfilm

Star Wars now had a setting, a plot, and a style, but it still didn’t have a soul. Lucas’ next breakthrough came when he encountered the work of Joseph Campbell, who had demonstrated that many cultures’ legends and fairy tales follow the same basic template. “About the time I was doing the third draft I read The Hero With a Thousand Faces,” he later said, “and I started to realize I was following those rules unconsciously. So I said, I’ll make it fit more into that classic mold.” He became convinced that “There’s a whole generation growing up without any kind of fairy tales,” he said, “and kids need fairy tales.” So he strove to make Star Wars follow each of the steps of “the hero’s journey” as laid out by Campbell: “The call to adventure” (R2-D2 shows Luke Princess Leia’s plea for help); “the refusal of the call” (Luke thinks he should stay home with his family); “supernatural aid” (the Jedi Obi-Wan); “crossing the threshold” (Luke escapes Tatooine); “the belly of the whale” (the trash compactor inside the Death Star); “the meeting with the goddess” (Leia); and so on.

Lucas kept incorporating more mythic and religious elements. Obi-Wan evolved a bit: a little less Toshiro Mifune’s samurai, a little more Carlos Castaneda’s Don Juan, a man with mysterious powers who speaks of a “life force.” (Castaneda’s New Age texts also later informed some of the teachings of Yoda, who intones, “Luminous beings are we”—Yoda-speak for Don Juan’s “We are luminous beings.”) More mainstream American religious intonation made its way into the screenplay as well; the Jedi started to speak the phrase “May the Force be with you” (a spin on “May the Lord be with you”). Of Campbell’s writing, Lucas later said, “It’s possible that if I hadn’t come across that, I’d still be writing Star Wars today.”

Here’s Looking at You

“Make Han in bar like Bogart—freelance tough guy for hire.”

— Note for early draft

As the screenplay was starting to take shape, Lucas brought in illustrator Ralph McQuarrie to help fill out the look of the world. His ideas for the movie’s visual design were just as referential. Drop Rick’s Café Américain from Casablanca onto a faraway planet and you’ve got the Mos Eisley Cantina: a bar in a port town with North African architecture (the sequence was filmed in Tunisia), where smugglers, refugees, and fugitives convene to smoke hookah, listen to the house jazz band, and seek passage away from military occupation. Jabba the Hutt, whose on-screen appearance was cut from the original Star Wars, would be modeled after Rick’s rival, Signor Ferrari: a large, round man and a major player in the underworld who oversees smuggling. (In one conceptual illustration, Jabba was even given a fez like Ferrari’s.) Whether by deliberate homage or coincidence, even the price of escape is more or less the same: The rate for a boat out of Casablanca is 15,000 francs, while in Star Wars, Obi-Wan promises Han 15,000 credits when they reach Alderaan.

Image by Slate. Film stills from Star Wars via Lucasfilm, Casablanca via Warner Bros.

Other movies influenced the film’s look as well. Lawrence of Arabia was a major influence on how Lucas shot the deserts of Tatooine, and as the desert-dwelling Kenobi he cast one of that 1962 classic’s stars, Alec Guinness. For the visual effects and spaceship designs, Lucas hired so many artists who had worked on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey that they became known as the “class of 2001.” Star Wars includes at least one declared homage to the envelope-pushing sci-fi movie: the Ubrikkian Landspeeder 9000 Z001, which puns all at once on Kubrickian, HAL 9000, and 2001.

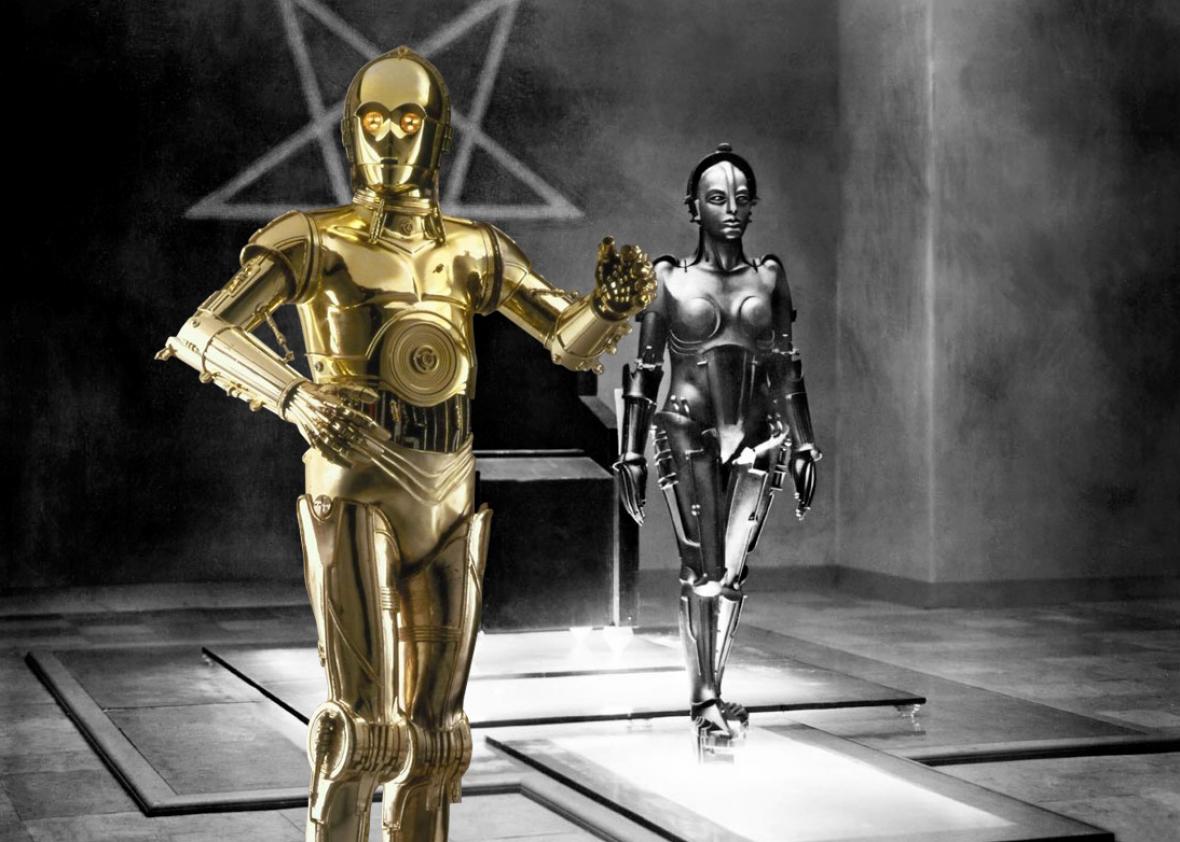

As for the droids, Lucas’ reference was baldly stated: “I showed Ralph the Metropolis robot and the Silent Running robot,” Lucas said, “and I said I want something like this.”

Image by Slate, source images from Star Wars via Lucasfilm, Metropolis via UFA

Image by Slate, source images from Star Wars via Lucasfilm, Silent Running via Universal

Not that Lucas drew only from the movies. Chewbacca, for example, was modeled after his Alaskan malamute, Indiana. Tatooine, a place where there was little to do but race speeders, bore a resemblance to flat, unexciting Modesto, where Lucas had discovered that the claylike soil was a first-rate surface for testing your top speed. And then there was the influence of Vietnam. Lucas had spent years developing Apocalypse Now (1979) with John Milius, but circumstances never lined up for him to direct it. “A lot of my interest in Apocalypse Now was carried over into Star Wars,” he later explained, noting that his work on the movie helped inspire the idea of “a large technological empire going after a small group of freedom fighters or human beings.” His notes included lines such as “The empire is like America ten years from now” and in one deleted scene, Luke even worries about getting “drafted into the Imperial Starfleet.” Lucas and his team drew from all corners of the world when designing the Empire—including most obviously World War I and World War II Germany (“stormtroopers”)—but the Star Destroyers were specifically modeled on Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet.

Image by Slate, photo via Wikipedia, still from Star Wars via Lucasfilm.

The Death Star Busters

“We cut the end battle scene out of all kinds of old war movies, everything from The Dam Busters and The Battle of Britain to documentaries and Tora! Tora! Tora!”

— George Lucas, January 1976

Animation via “Star Wars: Empire of Dreams Part 5 – ILM’s Challenge”/YouTube

The conceptual work of imagining Star Wars was nearly complete, but the movie still had to go out with a bang. Fortunately, Star Wars’ climax was one of the earliest sequences Lucas imagined for the movie, a “dogfight in space.” To draft his finale, he did something unusual: He literally cut together shots from old films. “Every time there was a war movie on television, like The Bridges at Toko-Ri, I would watch it,” he later explained, “and if there was a dogfight sequence, I would videotape it. Then we would transfer that to 16mm film, and I’d just edit it according to my story of Star Wars.” Lucas started videotaping off his TV as early as 1973, and the effects team later used his edits as a guide. Ken Ralston, who worked on the movie’s special effects, explained, “We matched frame-to-frame the action on that as closely as we could.”

The final run on the Death Star mirrors almost shot for shot the climax of Michael Anderson’s 1955 WWII thriller The Dam Busters. In Star Wars, Gold Squadron and Red Squadron make a series of small attack runs, flying low through a trench, avoiding the fire of turrets, to fire a single seemingly impossible shot at the Death Star’s only weak spot. In The Dam Busters, 617 Squadron must fly at low altitude through a river valley, avoiding the fire of anti-aircraft guns, to fire a single seemingly impossible shot at the dam’s only weak spot. Lucas seems to have cut-and-pasted some lines almost wholesale from The Dam Busters—just as Tarantino has copied lines essentially verbatim—and Lucas even hired cinematographer Gilbert Taylor, who had worked on The Dam Busters, to work on Star Wars.

“The Complete Tapestry”

“It should look very familiar but at the same time not be familiar at all.”

— George Lucas, 1975

Though it now holds a fraught place in cinematic history, there was little doubt about the greatness of Star Wars in 1977. Time called it “The Year’s Best Movie,” and it was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Director, and won six of them. Though it’s often blamed for today’s culture of sequels and remakes, unlike the nine highest-grossing films that came before it (Gone With the Wind, The Sound of Music, The Ten Commandments, Jaws, Doctor Zhivago, The Exorcist, Snow White, Ben-Hur, and One Hundred and One Dalmatians), it was an original story—albeit one consisting mostly of samples of other stories. Though it was far from the first cinematic pastiche (Leone had made his postmodern Westerns, Lucas’ friend Brian De Palma had begun to riff on Hitchcock movies, Peter Bogdanovich had begun to make homages like the screwball pastiche What’s Up, Doc?, and Godard was doing it at the art house with experiments such as the sci-fi noir Alphaville), it was the most eclectic, and the first to use the technique to forge a Hollywood pop blockbuster—blazing a trail that would later be followed by everything from Lucas and Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark to Blade Runner, Pulp Fiction, the Scream series, and Guardians of the Galaxy.

Viewers at the time understood they were seeing something that sliced and diced cinema history in a new and interesting way. Francis Ford Coppola compared it to a “complete tapestry” woven out of Flash Gordon and “a little bit of Hidden Fortress.” In his review in the New York Times, Vincent Canby called it “an apotheosis of ‘Flash Gordon’ serials and a witty critique that makes associations with a variety of literature that is nothing if not eclectic,” citing everything from Buck Rogers to The Wizard of Oz. In the Guardian, Derek Malcolm called it “an incredibly knowing movie” that “plays enough games to satisfy the most sophisticated”—noting the “direct allusions whipped from everything from The Searchers to the Triumph of the Will.” The article that perhaps best captured Star Wars’ achievements as a pastiche was the critic Roger Copeland’s in the Times. Headlined “When Films ‘Quote’ Films, They Create a New Mythology,” the September 1977 piece identified Star Wars’ debts to The Searchers, dogfighting movies, and Casablanca, and held it up as the most prominent example of a new kind of movie, the “film about other films.” Star Wars was “a film that makes so many references to earlier films and styles of filmmaking that it could just as easily—and perhaps more accurately—have been called ‘Genre Wars.’ ”

In the ensuing decades, the film’s mythology has become so essential to the American pop cultural experience that it has in some cases blotted out the source material on which Lucas drew. Writing of Star Wars’ place in the popular imagination in 1999, the critic J. Hoberman noted that the filmmaker Kevin Smith “remembers encountering classical mythology in school and assuming that the Greeks had ripped off Lucas.” Hoberman also pointed to a Newsweek article that described Campbell as the interpreter of Star Wars, when of course it was the other way around. If you require further evidence of Star Wars’ influence, just look to the movies that have done to Lucas what Lucas did to Kurosawa: Everything from The Fifth Element to Men in Black to Boogie Nights to Serenity to Lost to Up to Star Trek to Tomorrowland has paid tribute.

Image by Slate, posters via 20th Century Fox/Lucasfilm, Marvel

Will the new films honor the style that Lucas pioneered? There’s reason to hope that the franchise is in good hands. Writer-director J.J. Abrams has recently said that, before he started shooting The Force Awakens, he watched John Ford Westerns and Kurosawa’s 1963 High and Low. Rian Johnson, who’s writing and directing Episode VIII, is a filmmaker in the Lucas vein: He made his name with his 2005 film-noir pastiche Brick and remains hyper-referential even when he tries not to be. Since starting work on VIII, he has been screening 1949’s Twelve O’Clock High, one of the dogfighting movies Lucas re-edited for Star Wars, along with 1959’s Letter Never Sent.

If we’re lucky, we’ll discover that Abrams has soldered Episode VII together out of cinematic debris, just like the original. After all, one of the most important lessons of the original Star Wars is to never underestimate a bucket of bolts. Right at the center of the movie is a ship that might not look like much, but she’s got it where it counts—when she holds together, she’s the fastest hunk of junk in the galaxy. Let’s hope that baby’s still got a few surprises left in her.