Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Our Minds Are Intricate

Kathleen Collins’ remarkable stories feel like peeking through a keyhole at the inner lives of black women in another era.

Adi Embers

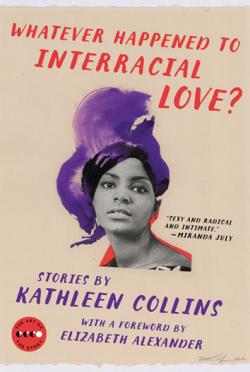

Reading Kathleen Collins’ Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? feels like peeking through a keyhole into the lives of black women in a bygone era. With stories set in the ’60s through the ’80s, Collins weaves fictional narratives about relationships gone awry, illicit love, and strained family dynamics with memoiristic details from her own life. Her stories are intense meditations on love, heartbreak, youthful ennui, gender, and race.

Collins was an award-winning playwright and filmmaker who died in 1988 from breast cancer, at the age of 46. Before the release of Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?, which was compiled by Collins’ daughter Nina, she was best known for her comic film Losing Ground, the story of the struggling marriage between a philosophy professor named Sarah and her painter husband, Victor. The story of one summer in Sara and Victor’s life could have easily been a story in Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? in the way it portrayed the delicate give-and-take in their marriage, the jealousy and the competition, and Sara’s eventual empowerment.

The title story in Collins’ new book, “Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?,” centers on the lives of two young civil rights activists, one black, one white. Recent graduates of elite liberal arts colleges, the two girls are living together in 1963, “the year of race-creed-color blindness,” as the narrator says. The story follows the girls through their respective interracial relationships and self-discovery. Cheryl, the black roommate, is caught between the expectations of her father and the opportunities gradually opening up to her. I imagine she was not unlike many young black women at the time in navigating a political awakening with the era’s respectability politics hanging over their head. It’s an atypical narrative—which is to say, one about a black woman—during an often-explored time in history. Ultimately, it’s a story that makes a sharp point about the era’s naïveté about race relations. In real life, Collins, an alumna of Skidmore College, was involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Albany Movement and spent the summer registering black voters in Georgia. She drew on her Francophilia and Sorbonne education for the story, “How Does One Say,” about a young black female student and her older French professor at a language immersion program in Maine.

Collins pays close attention to the minutiae of love lost. The opening story in the book, “Exteriors,” reads like the script of a relationship’s undoing. Structured as notes on a screenplay, the story ends with the narrator scribbling a note that the woman’s character should be left “in the shadow while she looks for the feelings that lit up the room.” Collins writes bluntly about the racial politics of love and sex. In the story “Stepping Back,” the narrator says:

I’m not trying to flatter myself, but I was the first colored woman he ever seriously considered loving. I know I was. The first one who had the kind of savoir faire he believed in so devoutly. The first one with class, style, poetry, taste, elegance, repartee and haute cuisine. Because, you know, a colored woman with class is still an exceptional creature.

Initially proud of her allegedly nonblack interests and attributes, the narrator ultimately reckons with her own inextricable blackness: “How could I occupy the splendid four-poster bed? Tastefully enough. And make love? Tastefully enough? No colored woman could. No colored woman could. No colored woman could.” Only sex could remove her carefully crafted façade.

The stories in this collection are often conversational and candid, as though the reader has been invited to have a chat with the narrator. I read Collins’ stories and saw glimpses of myself and other black women in my life reflected back. Though separated by three generations from Collins, I related to the experience of being a black woman at a predominantly white college, the ambivalence of my early 20s, and finding my footing during a similarly charged political moment in history. Collins’ characters grapple with the intersection of their blackness and their womanhood, working out what those identities mean for them. Black womanhood is still an unexplored concept in the national imagination; to see this groundwork laid by Collins is refreshing.

There are shades in the intimacy and urgency of Collins’ writing of Lorraine Hansberry and Zora Neale Hurston. Hansberry also died young, at the age of 34, to pancreatic cancer, though she had already reached commercial success with her play A Raisin in the Sun by the time of her death. Zora Neale Hurston was a prominent member of the Harlem Renaissance during the ’30s, but died in obscurity. It is only because of writer Alice Walker’s active interest in rediscovering Hurston’s work in the ’70s that it re-entered contemporary conversation. How many black women and their genius have been nearly, or completely, lost to history?

Kathleen Collins was a black woman who lived at a time, quite simply, when black women’s stories were not valued. Collins once said as much herself when reflecting on how difficult it was to get her movies made: “Nobody would give any money to a black woman to direct a film. It was probably the most discouraging time of my life.” If not for the persistence of her daughter in bringing her work to the world, Collins’ sharp and lovely stories would be lost. As the poet Elizabeth Alexander notes in her introduction:

The very existence of this book feels to me like an assurance that while we may think we have done our archival work and unearthed all the treasures of black thinking women, there is always something more to find. We have literary foremothers who are not just the ones we know we had, who continue to remind us of ourselves: Our minds are intricate. Our desires are complex. We are gorgeously contradictory in our epistemologies. We were not invented yesterday.

Collins’ work will certainly be canonized now, but what a shame that didn’t happen earlier.

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? by Kathleen Collins. Ecco.

Read the rest of the pieces in the Slate Book Review.

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?: Stories

Check out this great listen on Audible.com. Now available in Ecco's Art of the Story series: a never-before-published collection of stories from a brilliant yet little known African American artist and filmmaker - a contemporary of revered writers including Toni Cade Bambara, Laurie Colwin, Ann B...