Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Or and Or

Carl Phillips’ poetry is haunted by all that cannot co-exist.

Illustration by Peter Bagge

Bruised past ripeness, all the action offstage, overwhelmed with beauty and always threatening to dissolve, Carl Phillips’ Silverchest is an unlikely candidate for my favorite book of the year. Yet I doubt any new poetry collection has given me as much pleasure as this unusually—generously—slender, wintering tome.

Part of that comes down to abundance: Phillips just writes so damned well, a rich ear interlocking his phenomenal powers of perception and imagination. Take for example the almost violent metonymy in the first words of the three-lined poem “Brace of Antlers:” “Abbreviation for the animal’s head.” He observes gulls in a snow storm, “the wind in sudden gusts/ lifting their feathers,/ then the feathers finding again/ those positions that make flight, for a time, look/ possible.” In another poem the moods and moments give way to each other with such terrible speed that the result, in spite of what he describes, is closer to awe than despair—and closer to absolution than erasure:

the grass and

the imaginary conversation it makes

with itself…

Or any man in tears, whispering If

I go down on whoever tells me to, is it prayer,

isn’t it, did I pray

enough?

Waves,

then waves in reverse—

maybe that’s all we’re given.

But damned good somehow never seems like enough to justify poetry’s inbuilt isolation—its typographic and temperamental incompletion. As that last excerpt’s persistent entangling suggests, it’s Phillips’ inability that makes his poems take root: his inability to ever pull free of the counterweight hanging on to his ideas, a kind of gravity that measures significance by the very strength of its resistance to anything he hopes to mean. Even as he argues in favor of investing in illusion, he seems compelled to do so with scrupulous honesty:

As for the so-called waters of persuasion,

why not cast what’s left of belief

upon them?

As when we come to love a thing

for no better reason than that we have found it,

and find it wants for love. Have you ever

done that?

For Phillips, a classics scholar and the author of 11 collections of poems before this one, Silverchest is a book of active ambivalence. It’s a book, that is, of “or”—a word that appears 38 times in Silverchest’s 35 very short poems. Looking out from the haunted aftermath of love (the death of a lover seems to lurk in the background, though it’s never definitively named), Phillips struggles with the persistence of desire after the demise of belief. That desire frequently leads to “fucking” but only rarely summons thoughts of “love,” and those haunted ors register his refusal to choose between things that cannot co-exist, that sometimes cannot exist at all, as in the concluding iambic sentences—the latter an exact pentameter—of “So the Mind Like a Gate Swings Open”:

What’s

wrong with me, I used to ask, but usually too late, and not

meaning it anyway. He touches me, or I touch him, or don’t.

The haunting starts with the book’s very first line, “There’s a weed whose name I’ve meant all summer,” a sentence that manages to reach persuasively and tantalizingly beyond the brim of comprehension. (How do you mean a name?) But just past the line-break, the possibility of such meaning retracts: “There’s a weed whose name I’ve meant all summer / to find out.” The richer, more elusive significance gives way to a simple declaration of complacency, and yet its prospect stays intact, as does the more general sense in this book of decommissioned meanings running alongside and against the life that remains.

Phillip has a gift for making a sentence into a dramatic act, relentlessly unfolding some new and sometimes contradictory significance just beyond the next pause, so that the destructive offices of time and vulnerability also become a creative force:

I know a man who routinely asks

that I humiliate him. It’s sex, and it isn’t—

whatever. For him, it’s a need, the way

brutality can seem for so long a likely

answer, that

it becomes the answer—

a kindness, even, and I have always

been kind, for which reason it goes

against my nature to do what he says, but

there’s little in nature that won’t, with

enough training, change…

Those lines inaugurate one of the longest poems here, “Anyone Who Had a Heart,” which clocks in at 33 lines. It ends with them watching the horses in the man’s stables after sex. Standing on the other side of so much harm, including the harm that has hardened into kindness in the lines above, Phillips concludes, “Like broken kings, / they lower their heads, then raise them.”

As with so many of the moments in Silverchest, that final image of redemption exists only inside the terms of defeat. Many of Phillips’ most beautiful phrases turn out, when you go back and look again, to be unreal; they bloom deep inside a complex syntax in which they’re subordinate, already negated or merely a metaphor for something else. Many begin with “the way,” a generalizing phrase that Phillips often follows with his most specific descriptions.

Dinty W. Moore

It’s syntax as a model of survival. Set primarily in leaf-fall, ice and snow, these poems map a slow and peculiar resurrection: of the lover who lives on, rather than the dead lover who took an image of the speaker’s body into the earth with him. (In the title poem, Phillips refers to him as “the dark that nothing, not even the light, displaces.”) Phillips eventually chooses life—and achieves significance—but only by declining the richer significances that turned ghostly somewhere before the book began.

Partway through the stunning “My Meadow, My Twilight,” he writes:

But to look up from the leaves, remember,

is a choice also, as if up from the shame of it all,

the promiscuity, the seeing-how-nothing-now-will-

save-you, up to the wind-stripped branches shadow-

signing the ground before you the way, lately, all

the branches seem to, or you like to say they do,

which is at least half of the way, isn’t it, toward

belief—whatever, in the end, belief

is…

The rest of the poem—another 13 lines—occupies a single sentence, too intricate to quote in less than full. Hovering over it all, the double “my” of the title feels like an important concession. The providence, here, when there is provision, is not so much in the world that Phillips describes as it is in the challenged art of description itself. Phillips’ humility brings him to beauty. And his inability to account for his place among the living has allowed him to make the interplay between illusion and awareness into the one book this year that most richly and persuasively, at least for me, reinstates the possibility of finding meaning in a world that is forever ready to revoke the sources of meaning in our lives.

---

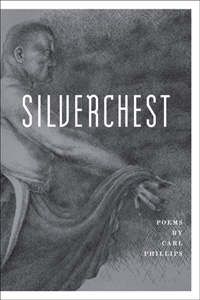

Silverchest by Carl Phillips. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.