Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Meg Wolitzer and Sarah McGrath

The Slate Book Review author-editor interview.

Sarah McGrath has been editing Meg Wolitzer since The Wife, in 2003. The editor and novelist emailed recently about Wolitzer’s new novel The Interestings, out this month from Riverhead.

Sarah McGrath: Meg, having known you as long as I have, and all the conversations we’ve had in that time about books and writing and careers and also life and friendship and aging, I have the sense that many of the ideas behind The Interestings are things you’ve done a great deal of thinking about. Do you have the same sense that I do, that this is a book that you’ve been building for a long time?

Meg Wolitzer: That’s certainly true, though I don't think I realized it until I was well into it. What I knew initially was that I wanted to write about what happens to talent over time—and do it by following a group of friends who know each other from adolescence through middle age, having met at a summer camp for talented teenagers. But once the essential premise got underway, I saw that maybe it wasn’t an accident that I’d chosen a book that required a big sweep of time. And in fact that choice was related to the way I'd been thinking about life more and more.

McGrath: And what exactly was that way?

Wolitzer: Well, I suppose I’d been focusing on changes that people undergo over years and decades. I’d been thinking a lot about who'd dropped away, who’d become well-known, who’d become lonely, who was dead. There were a lot of obsessive thoughts about who was dead. I’m still shocked at the deaths of friends, even years and years later.

McGrath: The fact that you let more of the city and the world in, along with all the people in this book—and there’s a pretty substantial cast of characters—makes me feel that your whole conception of a novel was changing.

Wolitzer: You know, I started publishing novels very young. I sold my first book, Sleepwalking, when I was a senior at Brown. And it came out the year after I graduated. But I have the sense that even though I started young, I began to mature late.

McGrath: I think your early work is pretty sophisticated.

Wolitzer: Well, I was more intuitive than anything else. I wanted the sentences to be fine, and I cared about style. Those things still do matter to me, of course. But the overarching sense of what a novel could be wasn’t something I thought much about. And it kind of stayed this way for a long time. Pretty much until I started my novel The Wife, at which point I woke up a little, and wanted to challenge myself more in my work, and write a novel that was tighter and, I guess, bolder.

McGrath: This was conscious? That you should write in a different way?

Wolitzer: It was more like, the books I liked reading felt both freer and more focused than the ones I was writing. And I didn’t know why that was. I started thinking that what makes novels work is an imperative that propels them forward, and I hadn’t always had that. And as I’ve gotten “mature”—which makes it sound like I’m talking about going through puberty here in delightful middle age—I guess I mean that I now feel compelled to try and make my books more urgent.

McGrath: What do you mean by urgency?

Wolitzer: I’ve had moments, quite a few pages into reading a book, when I’ll think, irritably, Who the hell are Susan and Jeff, and why am I supposed to care about their marriage? Maybe the writer hasn’t found the imperative. Which isn’t to say that good writing can’t be both good and leisurely.

McGrath: Or beautiful.

Wolitzer: Exactly. Leisurely and beautiful is maybe my dream. But you need to give the reader a sense of why you are “telling them this.” Why they need to become absorbed in your story and your language. It’s really difficult to do; I worry about it whenever I look over new pages I’ve written.

McGrath: As your editor, naturally I’m biased. I feel that The Interestings totally has what you call imperative. Some of the writing is beautiful, too. I wouldn’t call it leisurely, though it’s pretty long, for you.

Wolitzer: My new nickname is William T. Vollmann.

McGrath: But your book is really a “big” novel in all senses of the word. Big in size, broader in its coverage of time, and the changes in people’s lives, and it’s ambitious in scope, and it’s also accompanied by “big book buzz.”

Wolitzer: Oh God … “And all her hopes for the novel were dashed on the rocks below.”

McGrath: Of course, this topic of how fiction is perceived, big or small, is something you wrote about in a now famous essay in the New York Times Book Review almost exactly a year ago. Which came first, the ambition and vision for the book, or the insights that went into the essay?

Wolitzer: I have a chicken and egg answer, I think. I've been absorbed for a long time in questions about men and women and fiction; I tried to address them—or impale them—in The Wife 10 years ago. Since that time, these ideas have sometimes found their way sort of obliquely into my fiction, and other times they've simply made for a passionate conversation.

I knew I wanted to write an essay about this, because it was what I thought about all the time. As I kept playing with ideas about the different ways literature by men and women is often treated, I was also deep into The Interestings. But as I mapped out the essay, I may have also (coincidentally or not) allowed myself to try and put a little more unconflicted muscularity and energy in my novel. I mean, you may not be able to control how your book will be treated, but no matter who you are, you have to write what absorbs and preoccupies you. There's no point otherwise. Thinking directly about gender issues, which do absorb and preoccupy me, I guess—and also looking at the atrocious VIDA numbers—did light something up in me, and at least some of that light was applied directly to my fiction.

McGrath: “Gender issues”—I’m glad you brought that up.

Wolitzer: But I bet you’re not surprised I did.

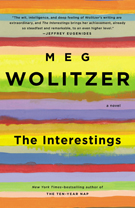

McGrath: No I’m not. One of the elements you mentioned in your essay for the Times was the difference between the jacket designs for novels written by men and those for novels written by women. You wrote about the soft, figurative, domestic-looking covers of novels by some women, and the big-lettered, bolder covers of novels by men. And you suggested that these covers sent varying messages of importance and authority.

Wolitzer: They absolutely do. People have told me that they’ve asked to have more input into how their books look, and I think that’s great. I mean, it’s your book. It has to look like a book you’d be proud to have written. A book that’s not marginalized by its cover, and that both men and women will take seriously.

McGrath: As a result of your piece, we approached the art for this book with particular sensitivity to these ideas, and the art department was given a copy of your essay along with the manuscript. How did we do?

Wolitzer: Wonderfully.

McGrath: Thanks, I’m glad.

Wolitzer: The book is beautiful and inviting, but it’s also gender-neutral, with bold lettering. It's a design-based cover that I really love.

McGrath: Yes, and I also feel that it doesn't seem to warn potential male readers away by using what you described as coded images to tell them that this is a book solely for women.

Wolitzer: I really appreciate the way the art department—and you—worked carefully with what I wanted to express. Not just about gender, but also about intention. This is a book about friendship, envy, and talent. It needed a cover that feels partly young, because the characters are often young in here. And I think it needed a cover that hints at an earlier era—the 1970s, the decade that opens the book, but then it moves back and forth between the present and then—but evokes a feeling of some deep nostalgia and beauty, and makes the reader say, “Let me in.” This cover is like walking into a painting done at summer camp by a very young Mark Rothko.

McGrath: Wow, I will pass that along. That’s a nice—if broad—segue into talking about our relationship: editor and writer. Maybe you could briefly describe how you think we work together—what the process is, from your perspective.

Wolitzer: Sure. As you know, I tend to like to meet with you early on and tell you my "intentions." And then you question some of them, and respond positively to others. I usually scribble pages of notes, some of which are hard for me to understand later. Once, on a scrap of paper from lunch, I scrawled the note, "What does the book mean? And what does it REALLY mean?" Is this very different from how you work with your other writers, Sarah? I mean, I guess you do have other writers, but I don’t like to think about them. That was a joke.

McGrath: I have a very different process with almost every writer I work with, and it all depends on a variety of things, but largely it comes down to the writer’s personal process—whether they find it helpful to discuss the work early, or only when they’ve come out the other side. And whether the part they want or need help with is on the line, structure, story, character, or idea level.

Wolitzer: This sounds very scientific.

McGrath: Oh, it isn’t. You just have to feel the writer out in each case to see what he or she needs, and what will work best. You and I know each other particularly well, having worked on five books over 11 or 12 years.

Wolitzer: That sounds impressive when you put it like that.

McGrath: It is. And I think the trust we’ve built up allows for a liberation from judgment, which lets brainstorming conversations roam especially freely. And because you so clearly convey to me, early on, what you’re trying to achieve with a book, part of my job as we progress through the drafts is not just to make sure the book reads well, but to make sure you’re succeeding in your intentions.

Wolitzer: Listening to you say this, I’m reminded that I’m very, very lucky. I know some people who basically get a few comments left in the margins like little droppings. “Nice!” the editor writes, months after the writer handed it in. Or, “Make her more assertive.” I feel very grateful at how deeply you work, and how patient you are.

McGrath: And I feel grateful that you choose to wrestle with certain big-novel ideas. There was that book by Sheila Heti, How Should a Person Be? You’re like, How Should a Novel Be?

Wolitzer: And when I finally find the answer, you’ll be the first person I will tell.

---

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer. Riverhead.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.