Slate is an Amazon affiliate and may receive a commission from purchases you make through our links.

Bittersweet Tea

Tracy Thompson digs beneath the surface of the “New South.”

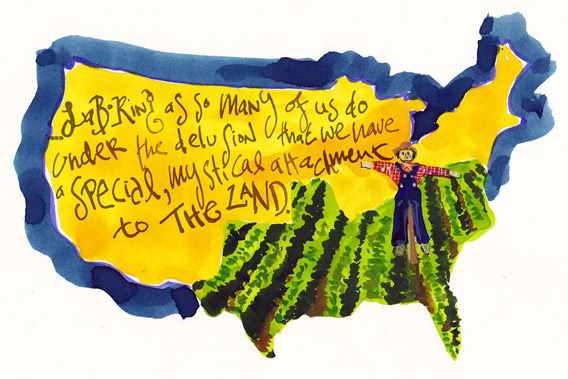

Illustration by Danny Gregory

You can listen to J. Bryan Lowder read this piece:

Growing up in rural South Carolina, I tended a large vegetable garden and a small orchard with my family. The land, given to my dad by his mother as a wedding present, had once been a cotton field. Of the yearly rituals involved with the garden, my favorite was the October tilling. A relative who made his living as a real farmer would come down to the house with his professional till and run it through our ground, turning the brittle old corn stalks and bean vines from the previous harvest under so they could disintegrate and enrich the soil for the coming spring’s planting. There was always something refreshing about it, seeing the topsoil unburdened of all that dead weight—not far off emotionally from the Sunday cycle of confession and forgiveness.

Pardon me for waxing misty about the Lowder family garden. In her quietly brilliant book The New Mind of the South, Tracy Thompson writes that Southerners have—or at least imagine they have—a unique relationship to dirt:

"Southerners may live in the heart of Manhattan, in a penthouse in Pairs, or in a condo in Buckhead—but if they identify themselves as Southerners, it means that somewhere, and probably not very far back, they have a close personal connection to the land: relatives who live in the rural South, a grandfather who farmed, a small town that is the ancestral family home, a cousin up in some holler who still talks with a twang. Lifelong residents of, say, Kansas may also lay claim to agrarian roots, but they don’t celebrate it the way Southerners tend to, laboring as so many of us do under the delusion that we have a special, mystical attachment to The Land."

Thompson knows exactly why I maintain my delusional dirt attachment—my potted herbs in Harlem somehow don’t satisfy it—but that tilling I remember so well gets at another point her book, a rigorous psychological profile told in the easy drawl of a homecoming story, has right about “our” people.

The problem with the modern South, as Thompson sees it, is the region’s desperate, almost pathological desire to till under a whole mess of historical refuse so that it can get on with being and branding itself “new.” But the difference is, these remnants—horrific racial violence, Jim Crow-era indignities, Lost Cause mythology, and, of course, the noxious sludge of slavery itself—will not fertilize the land; they will blight it. Indeed, since they have already been salt on the Southern earth for the 150 years since the Civil War, Thompson hopes that the ongoing sesquicentennial will show her fellow Southerners finally ready to suspend their famed cordiality for a spell in order to honestly, purgatively sort through the trash.

A Yankee couldn’t get away with this book. But Thompson’s upbringing in Georgia allows for an intimacy of insight (not to mention a pleasing front-porch cadence) that tempers her chastisements with a weary strain of compassion. She loves the South and, though she recognizes its many flaws, ultimately wants to see it heal. The medicine required is obvious from the outset: The South must face “the way it has assiduously cultivated, refined, and tended” the “myths, distortions, and strategic omissions” that define its deeply skewed sense of history. Southerners, Thompson notes, echoing the historian Carl Degler, have a peculiar sense of “two-ness”—that is, of cherishing their identity but knowing, if only in their guts, that something is fundamentally amiss behind the sweet tea and yes ma’ams.

On this diagnostic tour of the South’s kudzu-lined highways, Thompson’s cartographic eye is keen. She notices, for instance, when roads cross the railroad tracks into the black side of town or when they carry her past new megachurches proclaiming a brand of evangelicalism that does not comport with the gentle piety she recalls from her youth. In recounting the experience of feeling singled-out in a Baptist church that should have been welcoming (the day’s theme was about differentiating “true” Christians from poseurs), Thompson notes, with Southern understatement, that “the sermon that morning was enough to make a person wonder.”

Thompson also worries about how many roads now pass by Big Agra tracts instead of family farms and through hazy suburban sprawl instead of more sensibly—and sustainably—arranged communities. Most powerfully, she demands we remember that, not so long ago, people traveled in droves down from Atlanta to witness “the spectacle of a human being hacked up into pieces and roasted alive.” Southern roads, Thompson shows us, are haunted by the heat shimmers of the past and potholed by uncertainties in the present—and we must grapple with both if we’re ever going to get anywhere.

Courtesy of Dayna Smith

Some patch-jobs should be easy. For example, though many Southerners have been flustered by the influx of “Mexicans” (no matter the diversity of their actual national origins) into states like North Carolina over the past 20 years or so, Thompson points out the irony of rejecting a group of people whose conservative, family-centered morals almost exactly match a Southern ideal that is quickly in decline among whites. It may turn out that the much-maligned Mexican is more Southern than shrimp and grits—all that’s necessary, as Thompson jokes in a chapter title, is the addition of a little salsa.

Demographic shifts aside, Thompson’s analysis is most incisive—and heartfelt—when she turns to the South’s “Big Lie.” In high school, I encountered this lie from the well-meaning mouth of a history teacher (who spent his weekends as a Civil War re-enactor—go figure). Having been primed by a steady and totally disproportionate diet of “South Carolina history” (read: Civil War history) since elementary school, I was more than happy to accept the notion that the “War of Northern Aggression” was an equally valid title for the period of American history between 1861-1865 and that slavery was really only a minor issue in the decision to go to war. Abraham Lincoln was also a terrible president, constitutionally speaking (that part is somewhat true), and secession was and is a completely legal option in the toolbox of, you guessed it, states’ rights. Thompson uses fascinating archival research to show how upsettingly common my indoctrination into “Lost Cause” mythology is across the South to this day, thanks primarily to the curriculum-setting efforts of the founding members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

And I’m still not free of it, as I was reminded when I viscerally bristled at recent discussions surrounding Spielberg’s Lincoln in which no quarter was given to the idea that some of the South’s actions after the war might be excused by vengeful treatment at the hands of the Union. Presented with that kind of response, my high-school self suffers visions of Sherman burning Columbia. And then the familiar whispers of it wasn’t really only about the slaves and many of them were actually treated nice start to creep in. Only when my adult brain intervenes am I reminded that, oh yes, there are historical facts to contend with—like the fact that those fires may well have been set by Confederates.

But then, historical facts and historical feelings are difficult to marry. “A corollary to the lack of historical awareness is a certain lack of self-awareness,” Thompson writes. So many of us Southerners do not know—or are not willing to know—the factual truth of our own history (even as, ironically, many of us are family-Bible-obsessed with a feeling of the past), and so we do not know ourselves very well either.

Thompson knows that we are a capable, adaptable people but that we all too often think on a small, immediate scale. We love our families and close friends fiercely—these days, whatever color they are—and yet we cannot seem to address the larger problems of racial inequality and poverty corroding the steel roots of cities like Atlanta. We value personal property, private space, local autonomy, and the support of our neighbors and community, but those same values blind us to the fact that some struggles require cooperation on a larger, dare I say it, governmental scale. To truly refresh the land and make it ready for growth, we Southerners, white and black alike, must clean up some big, nasty, unpleasant shit. If we heed Thompson’s plea, if we can try together to finally detoxify those battlefields of the heart and mind, then maybe the South can actually be “new”—not merely rise again, but truly bloom.

---

The New Mind of the South by Tracy Thompson. Simon & Schuster.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.