Falling for Fallingwater

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Mount Vernon

House museums come in all shapes and sizes. Mount Vernon (left) and Monticello are preserved because they were the homes of two great men; moreover, Washington and Jefferson actually designed them. Houses where writers and artists lived and worked—Ernest Hemingway in Key West, Fla.; Augustus Saint-Gaudens in Cornish, N.H.; Louis Armstrong in Queens, N.Y.—are fascinating shrines to creativity. Then there are the homes of the super-rich, Hearst Castle in San Simeon, Calif., or Vizcaya in Miami, where one can be a snooping voyeur. Some house museums are neither grand nor particularly old—the Eames House in Pacific Palisades, Calif., Mies’ Farnsworth House in Plano, Ill., Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Conn.—but are architectural landmarks. The granddaddy of modern house museums is surely Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year. A new, superbly illustrated book is a reminder of just why this extraordinary building maintains such a strong hold on the American imagination.

-

Courtesy USPS.

Courtesy USPS.A Fallingwater Stamp

In 1982, Fallingwater appeared on a 20-cent U.S. stamp, part of a block of four, the others commemorating Walter Gropius’ house in Lincoln, Mass., Mies van der Rohe’s Illinois Institute of Technology, and Eero Saarinen’s Dulles Airport. The Gropius house appears outmatched, and although the Mies and Saarinen buildings are important works, they have none of the iconic power of Wright’s masterpiece. In fact, there is a lot more to Fallingwater than this view, but even at stamp size the image captures the geometry of the overhangs, the way that the house seems to grow out of the rock, and, of course, the fact that it sits on top of a waterfall. Wright’s client, Edgar J. Kaufmann, showed Wright his favorite spot on his property at Bear Run, Pa., an immense boulder next to a waterfall. Wright unexpectedly placed the house on the boulder. “E.J., I want you to live with the waterfall, not just look at it,” he told his client.

-

Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library/Columbia University.

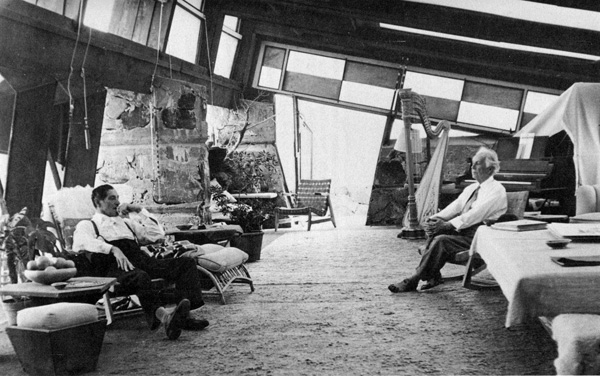

Courtesy Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library/Columbia University.Frank Lloyd Wright and Edgar Kaufmann at Taliesin West

Edgar Kaufmann, a wealthy Pittsburgh department store owner, was introduced to Wright by his son Edgar Jr., who was an apprentice for six months at the Taliesin Fellowship, Wright’s private-school-cum-office. Kaufmann père and Wright, both domineering personalities, hit it off, and the meeting led to several architectural commissions, including the weekend house at Bear Run. This photograph, taken in the 1940s, shows Wright and Kaufmann at Taliesin West, the architect’s winter retreat near Scottsdale, Ariz. This part of the living room was known as the music area; Wright was an accomplished pianist, while the concert harp* belonged to his daughter Iovanna. The roofs of the desert compound were canvas stretched over redwood frames supported by concrete and stone piers. The hassock and coffee table in the foreground are Wright’s design, but the rest of the furniture is charmingly eclectic.

*Correction: The article originally referred to the concert harp as a Celtic harp.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.The Fallingwater Living Room

Wright’s interiors are like landscapes in which the scattered groups of furniture resemble natural features. The polished flagstone floor of Fallingwater’s living room (left), which mimics the wet rocks in the stream outside, reinforces the metaphor, especially where it turns into a rock outcropping at the fireplace. The streamlined shapes above the fireplace are metal shelves that continue around the room and across the windows. The red spherical shape is a cast-iron kettle on a hinged arm that swings into the fire and was used for mulling wine. “You’ll hear the hiss,” said Wright. When not in use the kettle sat in a niche in the sandstone wall. Unlike most architects, he continuously varied the ceiling heights throughout, but the low ceiling of the living room, about 7 feet, is a surprise. Most of the rooms in Fallingwater have even lower ceilings. This has less to do with his stature—5 feet 8 inches—and more with the proportion of the exterior, and creating a sense of release as you move from inside to outside.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.Liliane Kaufmann’s Bedroom

The largest of the four bedrooms belonged to Kaufmann’s wife, Liliane. Her desk, like so much of the furniture, is built-in. All the Wright-designed furniture in the house is made of marine-quality plywood (to avoid warping) veneered with North Carolina black walnut. The Kaufmanns—wisely—resisted using Wright’s designs for sitting furniture, however, and except for his hassocks and built-in ottomans, the rest is a richly diverse mixture of modern designs (by Bruno Mathsson, Jorge Hardoy, László Gábor) and rustic pieces like the three-legged Florentine backstools in the living room, or this English peasant armchair. Wright designed the dramatic fireplace specifically to hold the 15th-century Madonna and child sculpture. The Kaufmanns’ interest in Native American crafts, such as this basket, was stimulated by trips they took in the Southwest with Wright and his wife, Olgivanna.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.Stairs to Nowhere

At one end of the living room, a sliding-glass panel that resembles a ship’s hatch provides access to a staircase that descends to the rushing stream and is one of Fallingwater’s trademark features. Initially conceived as a bathing platform, this function was obviated when it proved impractical to blast out the rocky streambed, which at this point is shallow. The Kaufmanns questioned the practicality of a stair that went nowhere, but Wright knew better; the stair links the house to the water in an almost mystical way. When the hatch is open, air from the stream cools the interior and the sound of the falls permeates the room. Although the stair appears to be suspended, it actually rests on the stream bed and the steel columns reinforce the structural “bolster” (visible on the right of the photograph), one of a series that support the cantilevered living room above.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.Exterior View

Fallingwater is a house of theatrical effects, but one of its charms is that there is no backstage. Whether you are on the stair going down to the water, sitting on one of the six outdoor terraces, or walking along the driveway (left), the house is integrated with its woodland setting. The three massive beams sitting on—or is it in?—the moss-covered boulder, support the terrace that leads off Edgar Kaufmann’s bedroom.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.Entrance

Fallingwater signaled a comeback for Wright. He was 67 when he designed the house and had been practicing for almost 50 years, but after his halcyon Prairie style period, his career hit several bumps, and many considered him a has-been. The public’s attention had been drawn to the so-called International style of a younger generation of Europeans: Richard Neutra, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius. According to Wright biographer Franklin Toker, when Wright saw the waterfall site at Bear Run on a preliminary visit, he told apprentice Cornelia Brierly, “Well, Cornelia, we are going to beat the Internationalists at their own game.” And he did. The pin-wheeling plan has been compared to Mies and the terraces take a cue from a California house by Neutra. The painted concrete appears International style (although it is painted light ochre rather than refrigerator white), and so does the abstract composition of planes, as in the entrance (left). On the other hand, there is nothing remotely machinelike about the house; it is a cave for living in.

-

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.

Photograph by Christopher Little/Rizzoli.The Iconic View

What makes this iconic view of Fallingwater so compelling is the crisscrossing terraces that appear to hover magically in the air, especially the upper one on the right, which Wright lengthened by 10 feet at the last minute. Once built, the lower terrace showed signs of sagging almost from the beginning, although Kaufmann, assured by Wright that the structure was sound, took no action. In 1995, alarmed at the cracks that continuously reappeared in the lower terrace, the conservancy that oversees the house commissioned an investigation. The engineers found that while the concrete was good quality, there was insufficient reinforcing in some of the supporting girders. They also discovered that although the upper terrace appeared to be hovering, it was actually partially supported by the lower terrace, thus adding to its load. To rectify the situation—and to prevent a catastrophic collapse—the beams under the lowest terrace were reinforced with post-tensioned cables. We can be thankful for modern technology, yet nothing can take away from the old magician’s accomplishment. Happy birthday, Fallingwater.