The Bauhaus

-

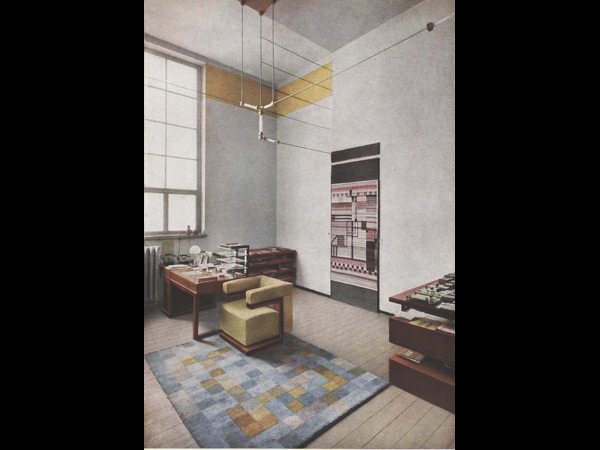

Director's office, Bauhaus, Weimar. Albert Langen Verlag, CREDIT: Bauhausbucher 7, 1925. The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York. © 2010 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Director's office, Bauhaus, Weimar. Albert Langen Verlag, CREDIT: Bauhausbucher 7, 1925. The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York. © 2010 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.The recent Bauhaus show at the Museum of Modern Art did not include this 1923 photograph of founder Walter Gropius' office, but it should have. The room is a quintessentially Bauhaus idea: the total environment. The furniture, carpet, wall hanging, and even the in-out tray were all designed and built at the school. The carpet is by Gertrud Arndt, the wall hanging by Else Mögelin; Gropius himself designed the furniture, as well as the elaborate lighting system. As Reyner Banham pointed out, the table lamp (also a Bauhaus product) was not part of Gropius' original design and was required to augment the ineffective, unshaded tubular lamps. But efficiency was never the point at the Bauhaus, which was always more about aesthetics than performance.

-

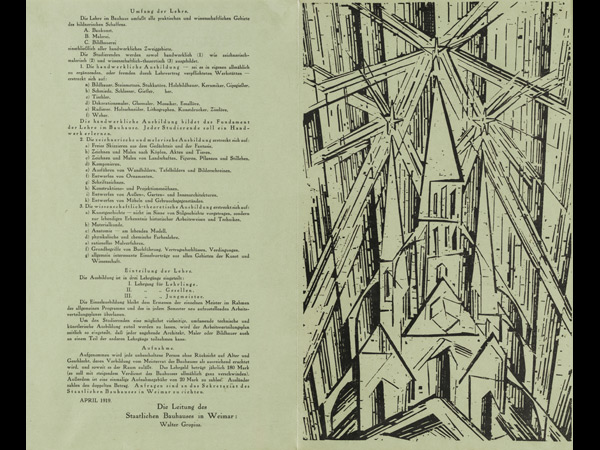

Lyonel Feininger, cover illustration, and Walter Gropius, text. Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the state Bauhaus in Weimar; also known as the Bauhaus Manifesto), April 1919. Woodcut with letterpress on green paper. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Julia Feininger. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Lyonel Feininger, cover illustration, and Walter Gropius, text. Programm des Staatlichen Bauhauses in Weimar (Program of the state Bauhaus in Weimar; also known as the Bauhaus Manifesto), April 1919. Woodcut with letterpress on green paper. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Julia Feininger. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.If the Bauhaus was more concerned with style than with technology, that was largely the result of its heritage. Despite its name—House of Building, which Mies van der Rohe caustically observed was Gropius' best idea—the Bauhaus began in 1919 in Weimar as a state-supported school of applied arts. The romantic ideals of its curriculum are expressed in the cover of a manifesto describing the program (right). The woodcut portrays not a house or a factory, but a stylized medieval cathedral. The artist was Lyonel Feininger, an American and Gropius' first hire. The cathedral—and the guilds that constructed it—symbolized the school's ideal of an integrated creative community. "There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman," Gropius announced.

-

Paul Klee, CREDIT: Maibild (May picture), 1925. Oil on cardboard nailed to wood with original strip frame. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Berggruen Klee Collection. © 2009 Artists Rights Society , New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Paul Klee, CREDIT: Maibild (May picture), 1925. Oil on cardboard nailed to wood with original strip frame. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The Berggruen Klee Collection. © 2009 Artists Rights Society , New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.Gropius, who had an uncanny ability to spot and recruit talent, gathered an extraordinary group of international artists to teach at the Bauhaus: Feininger; Oskar Schlemmer, a German; Paul Klee and Johannes Itten, both Swiss; the Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy; and Gropius' great catch, the Russian Wassily Kandinsky. It is notable that all the early masters, as they were called, were primarily painters, for the emphasis in the early days of the Bauhaus was on visual design, whether in graphics, color studies, posters, or furniture.

-

Marcel Breuer with textile by Gunta Stölzl, "African" or "Romantic" chair, 1921. Oak and cherry wood painted with water-soluble color and brocade of gold, hemp, wool, cotton, silk, and other fabric threads, interwoven by various techniques with twined hemp ground. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Acquired with funds provided by Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung.

Marcel Breuer with textile by Gunta Stölzl, "African" or "Romantic" chair, 1921. Oak and cherry wood painted with water-soluble color and brocade of gold, hemp, wool, cotton, silk, and other fabric threads, interwoven by various techniques with twined hemp ground. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Acquired with funds provided by Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung.This five-legged (!) armchair was designed and fabricated in 1921 by Marcel Breuer; the tapestry-woven seat and back were by Gunta Stölzl, another Bauhaus student. The design of the chair has been linked to peasant furniture from Breuer's native Hungary, although it looks more exotic to modern eyes, and Breuer later referred to it as his "African" chair. Its somewhat mystical, thronelike air probably represents the influence of Johannes Itten, whose introductory design course was a rite of passage for all young Bauhauslers. The charismatic Itten rivalled Gropius in the early days of the school, but by 1923, he had left as the curriculum shifted away from handicraft to industrial design.

-

The Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany; image taken in 2003. This image has been released into the public domain by its author, Mewes.

The Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany; image taken in 2003. This image has been released into the public domain by its author, Mewes.The ideological shift was accompanied by a physical move. In 1925, after the state government reduced funding, Gropius relocated the school to the city of Dessau, which offered not only financial support but also the opportunity to erect a new building. The complex, which housed workshops, an auditorium, a dining hall, and student residences (the teachers had their own Gropius-designed houses, some distance away) was anything but a medieval cathedral: an ultramodern factory, light, airy, transparent, "radiating power and optimism and a love of beauty," as Nicholas Fox Weber puts it in his lively new book, The Bauhaus Group. The building, Gropius' best work by far, was a perfect symbol for the new, industrially oriented Bauhaus.

-

Marianne Brandt, coffee and tea set, 1924. Silver and ebony, lid of sugar bowl made of glass. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Purchased with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Marianne Brandt, coffee and tea set, 1924. Silver and ebony, lid of sugar bowl made of glass. Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Purchased with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.Gropius became convinced that the role of the Bauhaus lay in "educating people to recognize the basic nature of the world in which they live," that is, an increasingly industrialized world. The workshops' output shifted away from handicraft to industrial prototypes—we would call it product design. In his practical way, Gropius hoped to make the school financially self-supporting by licensing Bauhaus designs to commercial manufacturers. This worked better in theory than in practice, but one of the successful exceptions was the work of the immensely talented Marianne Brandt, a student who became master of the metal workshop. Her exquisite designs, such as this silver and ebony tea set, perfectly capture the Bauhaus spirit and have become classics, still in production today.

-

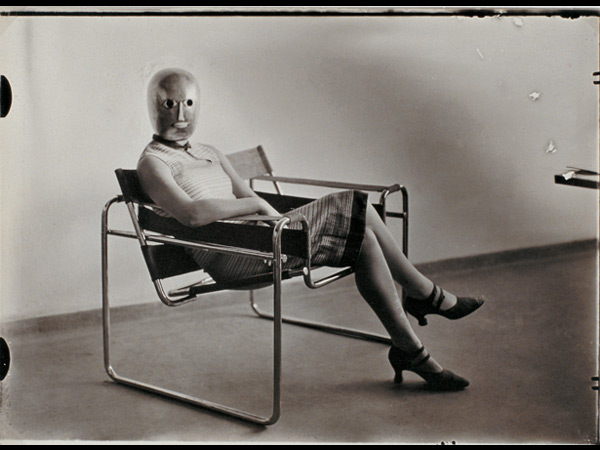

Erich Consemüller, Untitled (Woman in B3 club chair by Marcel Breuer wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer and a dress in fabric designed by Lis Beyer), circa 1926. Gelatin silver print. Private collection. © Estate of Erich Consemüller.

Erich Consemüller, Untitled (Woman in B3 club chair by Marcel Breuer wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer and a dress in fabric designed by Lis Beyer), circa 1926. Gelatin silver print. Private collection. © Estate of Erich Consemüller.The so-called "Wassily Chair," a chromed-steel and textile club chair designed by Breuer and named in honor of his colleague Kandinsky, has also become a classic. Extremely light, aggressively industrial-looking, the highly abstracted armchair—not especially comfortable, as I know from personal experience—epitomizes the Bauhauslers' conundrum. Were they making mass-produced consumer products or art? This 1926 photo emphasizes the latter. The model, who may be Gropius' wife, Ise, is wearing a mask by Oskar Schlemmer, who was in charge of the theater workshop.

-

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Lilly Reich Side chair, circa 1931. Tubular steel painted red with cane seat. Courtesy the Neue Galerie, New York. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe with Lilly Reich Side chair, circa 1931. Tubular steel painted red with cane seat. Courtesy the Neue Galerie, New York. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.In 1928, worn out by a decade of endless financial woes at the school (to which he contributed more than three-quarters of his salary), Gropius left the Bauhaus. His anointed successor was the architect Hannes Meyer, whom Gropius had brought in to lead the newly established architecture department. (For most of its life, the Bauhaus did not teach architecture.) Meyer lasted only two years. An outspoken Marxist ideologue, he alienated many of the teachers (Breuer, Moholy-Nagy, and Schlemmer left), as well as the Dessau city council, which asked for his resignation. His replacement was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (who had been Gropius' first choice). Mies restored order and discipline—and elegance, typified by this sidechair that he designed in 1931 with Lilly Reich, his mistress who also headed the weaving workshop.

-

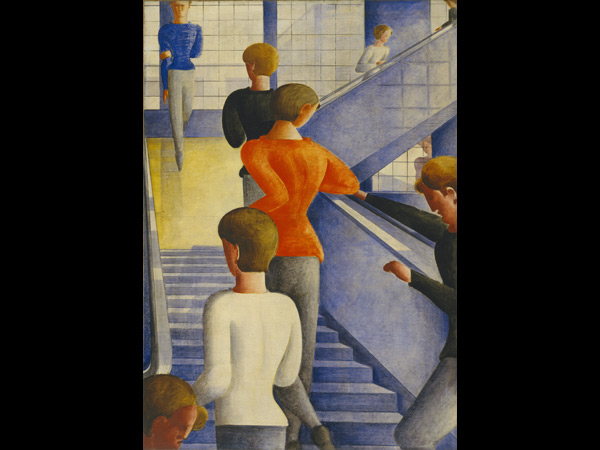

Oskar Schlemmer, CREDIT: Bauhaus Stairway, 1932. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Philip Johnson.

Oskar Schlemmer, CREDIT: Bauhaus Stairway, 1932. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Philip Johnson.Schlemmer's 1932 painting Bauhaus Stairway captures a fleeting moment in the life of the Bauhaus: students hurrying up the stairs between classes. In fact, there was very little time left. Later that year, after the Dessau city council discontinued funding, Mies moved the school to Berlin. There were now fewer students and fewer teachers—of the original masters, only Kandinsky remained. After nine months, and facing increasingly vocal Nazi opposition, the faculty voted to dissolve the school. It had existed a brief 14 years.

-

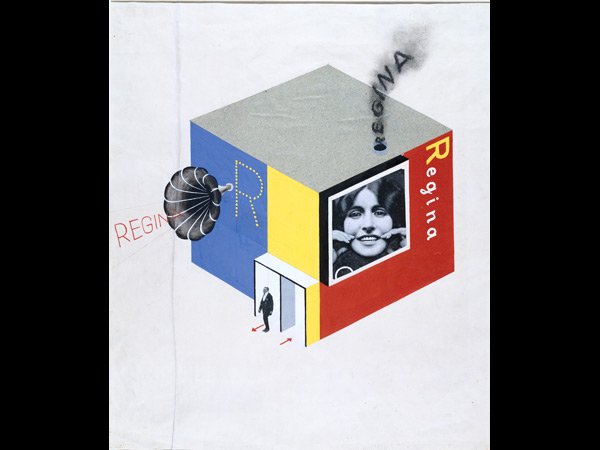

Herbert Bayer, design for a multimedia building, 1924. Gouache, cut-and-pasted photomechanical elements, charcoal, ink, and pencil on paper. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of the artist. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Herbert Bayer, design for a multimedia building, 1924. Gouache, cut-and-pasted photomechanical elements, charcoal, ink, and pencil on paper. Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of the artist. © 2009 Artists Rights Society, New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.Go into any IKEA superstore and you will see a sort of Bauhaus-Lite: knock-down shelving, lightweight furniture, geometrical lamps, bright colors, abstract patterns. While Gropius and his colleagues would have denied that there was a Bauhaus style, there was certainly a Bauhaus look. Light and spare, urbane, boldly embracing modern life in all its aspects—not only technological but even brashly commercial, as in this example of Reklame-Architektur (advertising architecture) with its loudspeaker, flashing sign, rear-projected movie, and smoke machine. The continued fascination exerted by the Bauhaus is due, no doubt, to its illustrious faculty and their imaginative output, whether paintings or teapots, but there is also the attractive image of a creative community bound together by art and design. Mies was wrong; that was Gropius' best idea.