Forgotten Eero

-

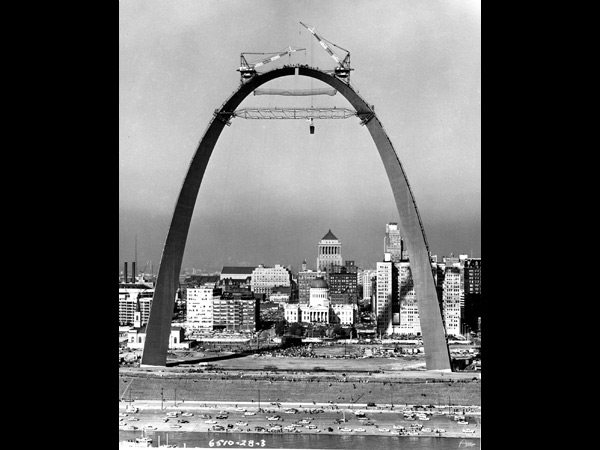

Construction of the U.S. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, 1965. From the Collections of Arteaga Photos Ltd.

Construction of the U.S. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, 1965. From the Collections of Arteaga Photos Ltd.The Gateway Arch in St. Louis is a rare case of a modern memorial that is as instantly recognizable as the Washington Monument or the Statue of Liberty. The 630-foot-tall stainless-steel arch is as grand as any Roman monument yet entirely modern in its pure abstraction. The architect, Eero Saarinen, was only 37 when he designed it, and if he had died right then he might be remembered as the F. Scott Fitzgerald of architecture. Instead, he went on to design more than 100 works, built and unbuilt, and was lionized during his lifetime but largely forgotten after his death (except as a regular clue in the New York Times crossword). Eero Saarinen: Shaping the Future, currently on display at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C., aims to change that. This large show, accompanied by a weighty catalog, attempts to make sense of this creative, complex, and frustratingly mercurial individual. Not an easy task, since while Saarinen was firmly a man of postwar America, he dedicated himself to questioning the orthodoxy of his time.

-

Courtesy Eero Saarinen Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University. Photograph by Scott Hyde.

Courtesy Eero Saarinen Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University. Photograph by Scott Hyde.Eero was born in 1910 in Finland, the son of Eliel Saarinen, himself a world-famous architect. In 1922, Eliel won second prize in the Chicago Tribune Tower competition, came to America, received a commission to build an artists' colony in Michigan (which became the Cranbrook Academy of Art), and stayed. Initially trained as a sculptor, Eero eventually switched to architecture, studied at Yale, and joined his father, working with him and teaching at Cranbrook. This Arts and Crafts version of the Bauhaus was a fertile training ground for the young architect. (Jayne Merkel's excellent architectural monograph provides details of this period.) Two of the people at Cranbrook who became his lifelong friends were architects and furniture designers Charles Eames and Florence Schust. The latter would be instrumental in furthering Saarinen's career as a furniture designer (they are shown at right in a 1957 photo, with the base of Saarinen's celebrated Pedestal Chair).

-

Knoll Inc.

Knoll Inc.Furniture was Eero Saarinen's chance to do something independent of his famous father. In 1940, he and Eames entered a Museum of Modern Art competition for home furnishings and won first prize with a molded plywood chair. Six years later, Florence, now married to Hans Knoll, with whom she had started a furniture company, challenged Saarinen: "I want a chair I can sit in sideways or any other way I want to sit in it," she told him. The result was the Knoll Model 70 Chair, the so-called Womb Chair (right). Since molded plywood proved too heavy, Saarinen devised a two-piece, folded, resin-bonded fiber shell, covering it with foam padding and upholstery. A small pillow supported the back. It is an ingenious solution: economic, comfortable, and pragmatically designed (the fiber shell is perched on a steel frame). Entirely unpolemical compared with some modern chairs, it is also sculpturally beautiful. The Womb Chair was introduced by Knoll in 1948 and has been in production for 60 years.

-

Copyright © 2008 GM Corp. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.

Copyright © 2008 GM Corp. Used with permission, GM Media Archive.Shortly before his father died in 1950, Eero took over the family business. His first commission, a vast technical center for General Motors on a 320-acre suburban site in Warren, Mich., would have daunted a lesser talent. Saarinen set aside an earlier design that he and his father had prepared and sought inspiration in Mies van der Rohe's Illinois Institute of Technology campus in Chicago, then under construction. The GM Technical Center owes a debt to Mies, but it is a small one. Saarinen's steel-and-glass-and-porcelain-enamel walls, developed with GM engineers, are high-precision skins, lacking the usual Miesian rhythm of structure and infill, and the overall layout is scaled to drivers rather than to pedestrians. The brightly colored, glazed brick walls (used to identify the six different divisions housed at the center), as well as the stainless-steel dome and water tower, are more sculptural—and more playful—than most '50s modern architecture. The serenity of the monumental basin was disrupted by a fanciful water-ballet fountain designed by Alexander Calder.

-

CopyrightCREDIT: © Balthazar Korab Ltd.

CopyrightCREDIT: © Balthazar Korab Ltd.Saarinen received commissions from some of the largest corporations in the country, building research laboratories for Bell Telephone and IBM, and an IBM manufacturing-and-administrative center in Rochester, Minn. (right). The sprawling, 100,000-square-foot building, housing a factory and offices, was wrapped in a highly refined metal skin only 5/16 inch thick. The enamel-coated aluminum panels were striped in two tones of blue, creating an illusion of depth, and were, Saarinen explained, "a chance to experiment with ornament." In 1956, this was heresy. So was the disassociation of form from function, for the exteriors of the factory and the offices were treated almost identically. Clearly, Saarinen was prepared to push the limits of Modernist dogma. Referring to the Miesian "glass box" idiom popular at that time, he said, "I cannot help but think that it's only the ABC of the alphabet, that architecture, if we're to bloom into a full, really great style of architecture, which I think we will, we have to learn many more letters."

-

CopyrightCREDIT: © Harold Corsini. Courtesy Eero Saarinen Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University.

CopyrightCREDIT: © Harold Corsini. Courtesy Eero Saarinen Collection. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University.Saarinen showed what he meant by "learning many more letters" in his best corporate building: the Deere & Company headquarters in Moline, Ill. Like most office buildings at that time, it was a glass box but was wrapped in a dense sunscreen made of structural steel. The steel, a corrosion-resistant alloy (Cor-Ten) developed for railroads but never before used architecturally, weathered to a rough, rust-colored finish. All those rugged I-beams seemed just right for Deere, a manufacturer of tractors and harvesters. Devising a style to suit a client was another Modernist heresy. Here, Saarinen was following in the footsteps of Raymond Hood, who in the 1920s had built memorable corporate icons for the American Radiator Company, the New York Daily News, McGraw-Hill, and RCA, the last at Rockefeller Center. Young Eero selected Hood as his thesis adviser at Yale, an interesting choice since it was Hood who had bested the elder Saarinen in the Chicago Tribune competition.

-

Photo by Michael Marsland. All rights reserved.

Photo by Michael Marsland. All rights reserved.Each commission was an opportunity to further expand the architectural alphabet; first D-E-F, then G-H-I. In college dormitories for Vassar, Chicago, and Penn, Saarinen created a modern architecture that responded to its historic architectural surroundings. At Yale's Morse and Stiles Colleges, he invented a rough concrete wall that would echo the nearby craggy neo-Gothic buildings (the tower of Payne Whitney Gymnasium is in the background, at right). The picturesque result turned out less neo-Gothic than peasant vernacular, however, and the colleges have often been likened to an Italian hill town. If the IBM manufacturing facility anticipated Norman Foster and the High-Tech movement, Morse and Stiles pointed the way to Charles Moore's Sea Ranch and Postmodernism. It must be said that the inflexible single rooms, basement common rooms, and rather austere architecture of Morse and Stiles have never been popular with Yale students.

-

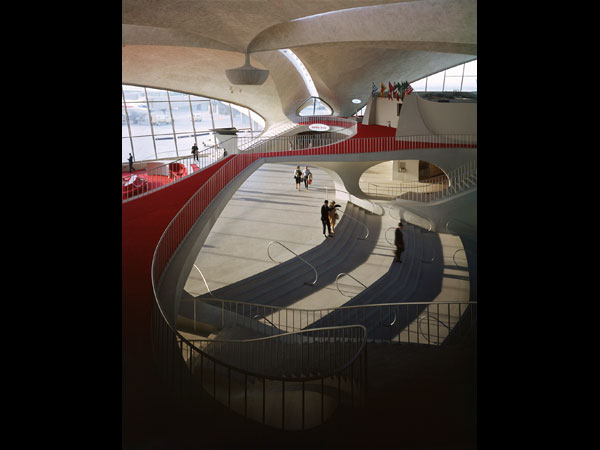

Photograph by Ezra Stoller. Copyright © Ezra Stoller/Esto.

Photograph by Ezra Stoller. Copyright © Ezra Stoller/Esto.Much to the critics' chagrin, Saarinen's work did not follow a straight-line trajectory. Unlike his contemporaries—Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, Minoru Yamasaki, and Edward Durell Stone—he did not stick to one style but went off in different, seemingly unrelated directions. At the same time as he was building Morse and Stiles, for example, he was also designing the most fanciful building of the 1950s, the TWA Terminal in New York's Idlewild (now JFK) Airport. Responding to his client's demand to convey "the spirit of flight," Saarinen, who had earlier designed a thin concrete vault at MIT, combined concrete shell construction with his sculptural training. He said that he always wanted his architecture to make people feel things, and nowhere is this truer than at TWA, which was a throwback to the German Expressionist architecture of Erich Mendelsohn. Another heresy, since modern architects were supposed to look forward, not backward. We now can see that TWA also anticipated the late-20th-century Expressionism of architects such as Greg Lynn and Zaha Hadid.

-

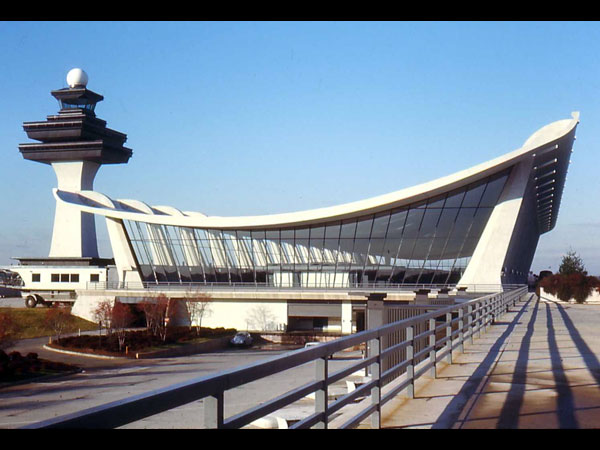

Photograph by John Dalkin.

Photograph by John Dalkin.TWA was not yet finished when Saarinen's office began working on a larger airport building. Dulles International Airport in Washington, D.C., was to be built from scratch, hence it was an opportunity to entirely rethink the way that an airport functioned. Saarinen did away with the long corridors and dispersed boarding gates of conventional airports. Instead, cars dropped passengers off on one side of the building, and so-called mobile lounges—another Saarinen invention—picked them up on the other and took them directly to the plane parked on the tarmac (right). The terminal had the simple axial logic of a Beaux-Arts plan: a large shed, designed to allow extension at either end (the length was doubled in 1996). The concrete roof, slightly higher on one side, was suspended between canted, sculptural columns. While TWA was more striking and had an iconic quality that the public found irresistible—"a bird in flight"—it was Dulles that Saarinen considered his best work, as indeed it is. It is a balanced combination of functional innovation, evocative space, and clear structural expression.

-

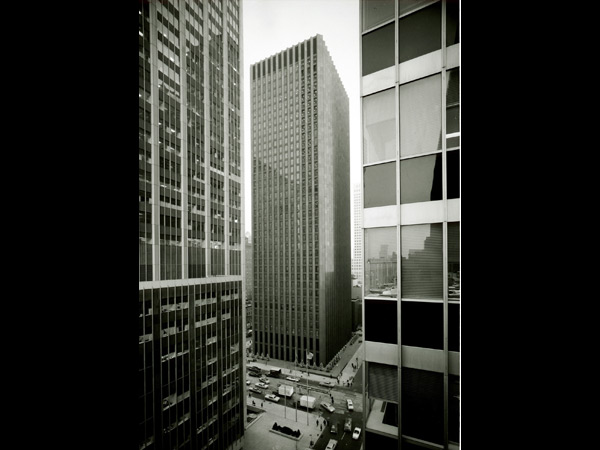

© CBS/Landov.

© CBS/Landov.The CBS Building in New York was Saarinen's first skyscraper. "I want to build a simpler building than any that's ever been built, including the Seagram Building," he told Philip Johnson, who had recently assisted Mies van der Rohe on the Seagram Tower. CBS is undoubtedly simple, a black extrusion that shoots straight up out of the ground, 38 stories. But its simplicity is also its failure; not for the first time, Saarinen's insistence on reinventing the wheel was his undoing. As Johnson once pointed out, the CBS Building lacks a top and a bottom. It also lacks a proper entrance; prosaic revolving doors are squeezed into 5-foot spaces between the V-shaped columns. Like Seagram, the building has a podium, but unlike almost any building anywhere, it is not elevated but unpleasantly sunk—2 feet below the sidewalk. New Yorkers call the building "Black Rock," referring to the dark tinted glass and rough black granite. It is a nickname that also captures the building's implacable, gloomy, and slightly threatening presence.

-

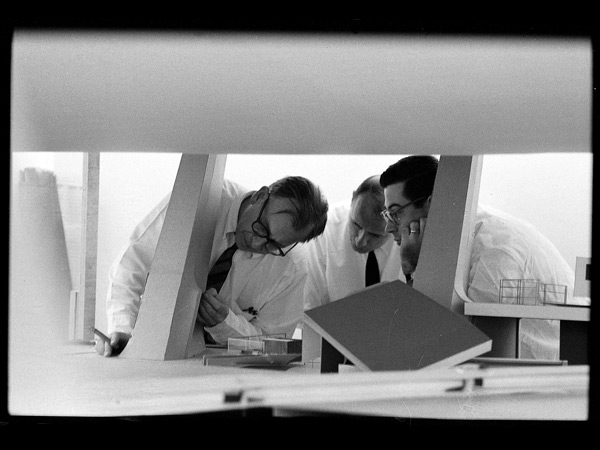

Eero Saarinen, with architects Kevin Roche and Norman Pettula and a model of Dulles International Airport, November 1959. Courtesy Richard Knight. From CREDIT: Saarinen's Quest: A Memoir.

Eero Saarinen, with architects Kevin Roche and Norman Pettula and a model of Dulles International Airport, November 1959. Courtesy Richard Knight. From CREDIT: Saarinen's Quest: A Memoir.In 1961, Saarinen died unexpectedly at 51 of a malignant brain tumor. Yet in only a dozen years he built more—and more memorably—than any of his contemporaries. Despite failures such as CBS and less-than-successful projects such as Morse and Stiles, he created several masterpieces, including the Womb Chair, the Gateway Arch, Deere, TWA, and Dulles. Yet what it all adds up to remains slightly perplexing. Having rediscovered Saarinen, where to put him in the architectural batting order? Certainly higher than Johnson and Rudolph, perhaps not as high as Louis Kahn, although there is a generosity of spirit in Saarinen's best work that is absent in Kahn's more guarded designs. Saarinen's restless talent, technological optimism, and broad range as an industrial designer and a sculptor seem out of step with our world. We prefer our architectural stars in discrete categories: artist, technician, corporate practitioner. Saarinen, a chameleon, could be all three.