Borrowed Time

-

Photograph by David Monack, licensed per Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.5.

Photograph by David Monack, licensed per Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike 2.5.A fight is brewing in Washington, D.C., between the city administration and preservationists concerning the District's central public library. The architect of the Martin Luther King Jr. Library was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, one of the seminal figures of the Modern movement, and while the '60s-era black box is not one of the master's great works, it is the only library that he ever built. Mies' architecture was intentionally impersonal and meant to be adaptable to future change, yet in 2006, a task force appointed by Mayor Anthony A. Williams found the library to be "an outmoded structure erected long before the advent of the digital world." It recommended selling the building to a developer (who would likely demolish it) and building a new library on another site. Historic preservation aside, this raises an interesting question: What sort of public library does the "digital world" of Google, Wikipedia, and Kindle require?

-

Photograph by Douglas Kaye.

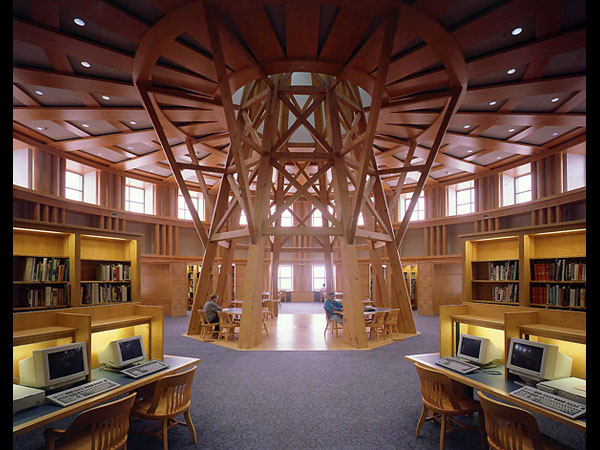

Photograph by Douglas Kaye.During the last two decades, many cities have grappled with this question and provided a variety of answers. One of the first—and the largest—was the Harold T. Washington Library in Chicago, designed by Hammond, Beeby & Babka in 1991. The interior was planned with stacks open to the public and large loft spaces for maximum flexibility—a bit like a department store. The lower levels contained such nontraditional spaces as a video theater and lending library, a gift shop, and exhibition spaces. But it was the exterior that made the strongest impression. The building incorporates many elements of 19th-century loop architecture: heavy stonework, arched windows, and decorative carving, as if Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, and John Root had come back to have another go. The result, massive and monumental, is a slightly forbidding Fortress of Knowledge.

-

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.San Francisco's new main public library (designed by Pei Cobb Freed) opened five years after Chicago's library and took a similar approach: an updated version of an early-20th-century civic monument. The staid Beaux-Arts architecture of the surrounding City Beautiful civic center provided the inspiration for the exterior, which belies an interior that is considerably more Modernistic, with a five-story rotunda and plenty of natural light.

-

© Peter Aaron/Esto.

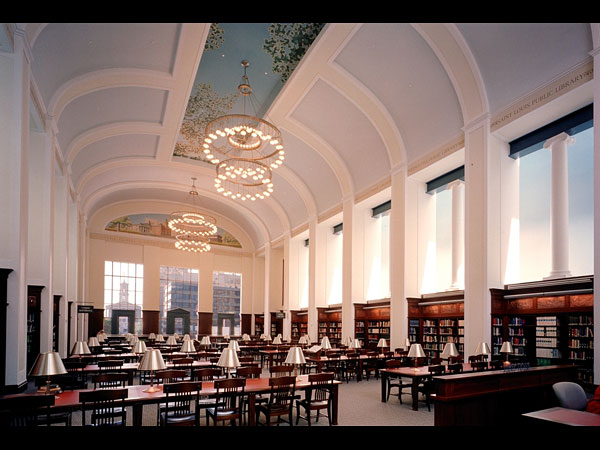

© Peter Aaron/Esto.The concept of the grand downtown library dates from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, when cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Chicago built ambitious public libraries. The chief symbolic space of these buildings was a magnificent reading room. Robert A.M. Stern Architects has recently built several downtown libraries in midtier cities such as Columbus, Ga., and Jacksonville, Clearwater, and Miami Beach in Florida. While designed in a variety of styles, they usually include impressive reading rooms, though few as directly evocative of the past as that of the Nashville Public Library (right), with its frescoed ceiling and traditional reading lamps.

-

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.The Denver Public Library, designed by Michael Graves, likewise has an impressive room: the Western History Reading Room. While Graves' slightly cartoonish, stripped Classicism lacks the self-conscious gravitas of Stern's design, it sends a similar message: Knowledge Is Important. Like the other new downtown libraries, the Denver Public Library sends another message: We Are Still Here. The library building boom of the last two decades is closely tied to efforts to rejuvenate downtowns. Cities can't re-create the department stores, movie palaces, and manufacturing lofts that once made downtowns the vital centers of American metropolitan life, so they build convention centers, ballparks, museums, and concert halls instead. Retro ballparks have enjoyed success with the public, but I'm not sure that trying to re-create the library-as-monument has an equal appeal.

-

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.Operating on the principle that the grand library of the past cannot be simply resurrected, some cities have taken a different tack. Seattle's new library, for example, doesn't have a reading room at all. Instead, Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Prince-Ramus of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture have designed a single, freewheeling space inside a giant, multilevel greenhouse. This is the library conceived as a drop-in center, filled with computer terminals, magazine and newspaper racks, lots of comfortable seats, and, yes, even bookshelves. Like most modern libraries—and unlike most traditional libraries—the stacks are open to the public, although as books become digitized, this part of the building is likely to shrink. The Seattle Public Library has the rough urban chic of a converted loft. When I visited, the users were a mix of students, tourists, and street people—many reading newspapers, even more using the computer consoles, very few in the stacks.

-

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.

Photograph by Timothy Hursley.Seattle's public library, unlike those of San Francisco or Chicago, was designed to be a downtown hangout, with something for everyone, as if you crossed Starbucks with a mega bookstore. Salt Lake City's public library goes one step further and adds a touch of the shopping mall. The architects, Moshe Safdie & Associates, made the focus of the building a skylit lobby-concourse, known as the "Urban Room." Like Milan's Galleria—the granddaddy of shopping malls—the dramatic space is a sort of indoor street, lined with shops. The library houses a cafe and a deli, a florist and a comic-book store, as well as an NPR station and a writing center. The book stacks and reference areas are on the left of the concourse; individual study carrels and reading nooks rise on the right. The result manages to be grandly civic and familiarly commonplace at the same time.

-

Photograph by Leonard G., licensed per Creative Commons ShareAlike 1.0.

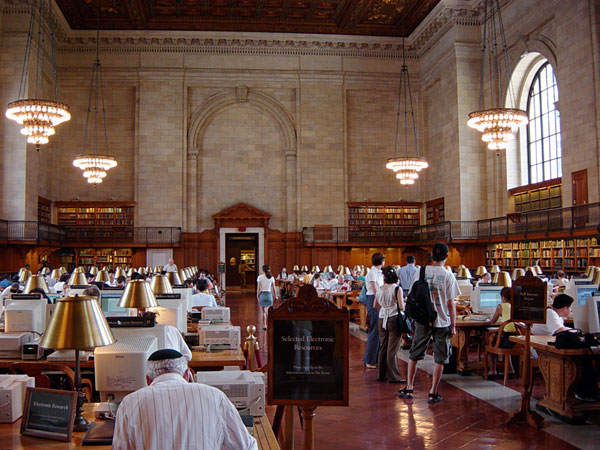

Photograph by Leonard G., licensed per Creative Commons ShareAlike 1.0.It's a long way—and almost 100 years—from Carrère & Hastings' inspiring reading room at the New York Public Library (right) to Safdie's "Urban Room" in Salt Lake City. Ross Dawson, a business consultant who tracks different customs, devices, and institutions on what he calls an Extinction Timeline, predicts that libraries will disappear in 2019. He's probably right as far as the function of the library as a civic monument, or as a public repository for books, is concerned. On the other hand, in its mutating role as urban hangout, meeting place, and arbiter of information, the public library seems far from spent. This has less to do with the digital world—or the digital word—than with the age-old need for human contact.