New York's Governors Island

-

Aerial View, Governors Island, 2004. © Andrew Moore.

Aerial View, Governors Island, 2004. © Andrew Moore.Governors Island lies half a mile off the southern tip of Manhattan. For more than 150 years, the island served as a military post and in 1966 became home to the U.S. Coast Guard. In 2003, the federal government handed over the decommissioned base to New York state and New York City. The plan is to turn 25 to 40 acres of the 172-acre island into a public park, including a two-mile waterfront promenade and space for unspecified educational uses. "The Park at the Center of the World" is the lyrical name of a current exhibition of five design proposals. The title is a play on The Island at the Center of the World, Russell Shorto's history of the Dutch in Manhattan, and conveys a similar sense of over-the-top civic boosterism. Yet it is not inappropriate. If not exactly in the center of the world, Governors Island is in the center of Upper New York Harbor—with extraordinary views of the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, Ellis Island, and the forest of skyscrapers in lower Manhattan.

-

WRT and Urban Strategies.

WRT and Urban Strategies.Governors Island consists of three parts: a national monument, incorporating Castle Williams and Fort Jay; a landmark district that encompasses many historic buildings and a parade ground; and the old Coast Guard residential area, which is to be demolished. Last January, the Governors Island Preservation and Education Corporation, charged with developing the island, selected five design teams from among 29 international submissions and asked them to prepare "conceptual and illustrative design ideas." The challenge is to turn Governors Island, which is only a seven-minute ferry ride from the Battery, into a high-profile destination for New Yorkers and tourists. The solution by WRT of Philadelphia and Urban Strategies of Toronto provides spaces for a wide variety of year-round activities: wildlife habitats, a working farm, parkland, a children's camp, a tobogganing hill, sculpture gardens, exhibition halls, restaurants, and a high-rise (!) hotel. This grab-bag approach produces a kind of sylvan theme park—something for everyone.

-

WRT and Urban Strategies.

WRT and Urban Strategies.Frederick Law Olmsted's naturalistic parks, with great expanses of greensward, clumps of trees, and irregular sheets of water, were built more than 100 years ago, but they remain the gold standard for landscape design as far as the public is concerned. Many contemporary landscape architects, however, want to get out from under Olmsted's giant shadow. Since the elements of a park have not changed much—trees, grass, and water—one solution is to arrange them differently. WRT's rather mainstream design, for example, replaces picturesque composition with abstract geometry, although the latter would be appreciated chiefly from the air.

-

Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture.

Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture.George Hargreaves, one of the best-known American landscape architects, has recently designed a 100-acre park, Crissy Field, on the site of a U.S. Army airstrip in San Francisco. The Hargreaves/Michael Maltzan Architecture proposal for Governors Island is similarly organized, with passive and active recreation situated in distinctly separate areas. Long diagonals (corresponding to the chief views) divide the open space into four landscapes: dunes and a beach; pines and meadow grasses; grassy athletic fields; and perennial gardens. The last form a backdrop to McKim, Mead & White's 1,000-foot-long facade of Liggett Hall, originally a battalion headquarters and barracks, to be redeveloped for educational or commercial use. An elevated promenade that more or less follows the shoreline loops around and through the different landscapes.

-

Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture.

Hargreaves Associates/Michael Maltzan Architecture.The landscape provides areas such as a pine barrens, overlooking a wind farm and the Statue of Liberty in the distance. In addition to such pastoral experiences, the proposal includes a number of new structures: an arrivals building at the ferry dock, a marine-ecology center, a hotel and conference center, a theater, and an amphitheater. Maltzan's attention-getting architecture, with its sculptural shapes and dramatic cantilevers, is intended to create a unique sense of place, but it threatens to overwhelm its surroundings. Letting the multifaceted landscape come to the fore might have been a better strategy.

-

West 8/Rogers Marvel/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM.

West 8/Rogers Marvel/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM.The third proposal is the work of a large team. Led by West 8, a prominent Dutch landscape and urban-design firm, it includes three architects, Rogers Marvel Architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Quennell Rothschild & Partners, as well as planning firm SMWM. Unfortunately, this multiplicity has not produced a coherent vision—at different points, the proposal speaks of a "paradise island," a "green island," a "national park." While the proposal covers all the bases—ecologically, educationally, and philosophically—and goes into exhaustive detail (there are even designs for a wooden "GI bicycle" for use by the public), it is not clear what it all adds up to.

-

West 8/Rogers Marvel/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM.

West 8/Rogers Marvel/Diller Scofidio + Renfro/Quennell Rothschild/SMWM.The two big landscape moves here are a new canal that bisects the island, allowing access to small ferry boats from Manhattan, and a "vertical landscape" of man-made buttes, some as tall as 17 stories and some hollowed out to include buildings. The aim is to create an exciting and fantastic environment, a sort of architectural Tivoli Gardens. The result could be delightful or kitschy, it's hard to say.

-

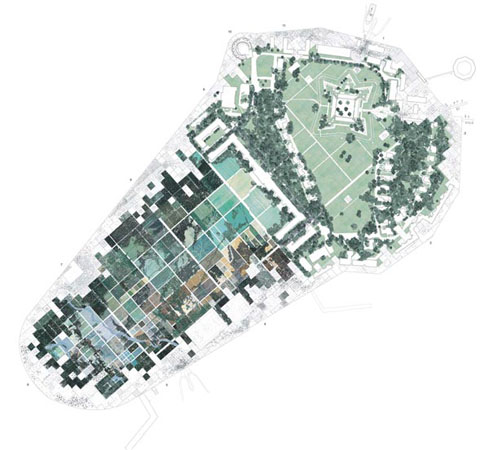

REX/MDP. Image by Luxigon.

REX/MDP. Image by Luxigon.Perhaps the most audacious proposal of the five is by Ramus Ella Architects of New York and Michel Desvigne Paysagistes of Paris. "This is not a landscape proposal. This is a development strategy," they proclaim. The strategy is to develop the perimeter of the island first, leaving the interior for gardening and small-scale agriculture. To this end, the entire area is divided into 55-by-55-foot squares. Given the vagaries of what will actually be built—and when—the giant checkerboard will provide a flexible and adaptable matrix for playing fields, orchards, pastureland, water meadows, pavilions, buildings ... whatever.

-

REX/MDP. Image by Luxigon.

REX/MDP. Image by Luxigon.Michel Desvigne has designed large public parks in London and Bordeaux based on the idea of an "intermediate landscape" that adjusts and changes over time as programmatic needs arise. It is an attractive concept, as the accompanying view shows, and feels like a good approach for Governors Island, whose future is far from secure (the many empty historic buildings, for example, have as yet no tenants, and developers have been leery of committing money to actual projects). Thus, the Ramus Ella/Desvigne proposal is sensibly devoid of fancy architecture, which may or may not come. However, a checkerboard—even when it's referred to as "Jeffersonian"—is a banal organizing device, and 40 acres of giant quilt might soon become wearying. Anyone who has the chutzpah to call Central Park "fake nature imprisoned by a grid," as these designers do, should come up with something more compelling.

-

Field Operations.

Field Operations.The five proposals are currently being exhibited at New York's Center for Architecture on LaGuardia Place in downtown Manhattan and on Governors Island, which is open for visitors Saturdays and Sundays through Sept. 1. A jury is expected to recommend a winner by this fall. Everyone seeing the exhibit will have a favorite; mine is the proposal by Field Operations, working with British architects WilkinsonEyre. (Full disclosure, James Corner of Field Operations is my colleague at the University of Pennsylvania, although in a different department.) These designers have understood something very important about this little island: 40 acres is a very small area for a park. Central Park encompasses 843 acres; at Brooklyn's Prospect Park, the lake alone covers 40 acres. So, instead of subdividing the parkland and cramming in as many features as possible, as the other proposals have done, Field Operations covers the entire southern end of the island with a single undulating meadow of grasses and wildflowers.

-

Field Operations.

Field Operations.The meadow is surrounded by a promenade, which in some places becomes a boardwalk, in others simply a paved bulwark. At one point the promenade turns into a causeway, with water on both sides; at another it is a hanging bridge, dramatic bridges being a WilkinsonEyre trademark. Architecture and landscape go hand in hand here. The mollusklike structures, which contain a weather institute, terraria pavilions, and public shelters, perch tentatively in the windblown, treeless terrain like seashells stranded on a beach. Tiny Governors Island, surrounded by an immensity of water, gives one a strong sense of precarious exposure to the elements, as well as a feeling of vulnerability. This minimalist design preserves and enhances the experience of what its designers call "remote otherness." The result is a distinctly modern park, although I think that Olmsted, who designed public parks in special places—a river island (Detroit's Belle Isle) and a mountaintop (Montreal's Mount Royal)—would have approved.