The Joy of Footbridges

-

Capilano Bridge, North Vancouver, British Columbia. Photograph by Leonard G., licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. Courtesy CREDIT: www.wikipedia.org.

Capilano Bridge, North Vancouver, British Columbia. Photograph by Leonard G., licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. Courtesy CREDIT: www.wikipedia.org.The Minneapolis bridge collapse earlier this year was a reminder of what a special sort of infrastructure a bridge is—different from a tunnel, a causeway, or an elevated highway. All bridges are to some extent gravity-defying, and some can be inspiring. At least to look at. Crossing a bridge—even a beautiful bridge—by car or train is often a letdown; the world seen through a guard rail. That's why footbridges are so special. You can stop in the center of the span, and with a quick turn of the head experience the illusion of standing in midair. Crossing a suspension footbridge, like the 450-foot Capilano Bridge (right) in North Vancouver, British Columbia, you can even feel the slight swaying of the structure. The venerable Capilano is the simplest of bridges—cedar planks slung onto steel cables—but recent footbridges have found many other ways of getting people from here to there, ways that allow architects and engineers to show off their ingenuity.

-

Millennium Bridge, London. Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

Millennium Bridge, London. Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The design of the Millennium Bridge in London was the result of an international competition won by engineers Arup, architects Foster and Partners, and sculptor Anthony Caro. Since the bridge over the Thames was required to be as light as possible, a suspension-type was called for, but since a low profile was also mandated, the bridge could not have any supporting masts. Instead, the eight suspension cables—four per side—are at the level of the deck. The bridge is more than 1,000 feet long (the longest unsupported span is 480 feet). Initial swaying, caused by the motion of walking people, was solved by installing dampers. The Millennium Bridge is purposeful rather than beautiful, but the real payoff, other than being able to conveniently reach the Tate Modern from the city, is a stirring view of Christopher Wren's dome of St. Paul's.

-

Puente de la Mujer, Buenos Aires, Argentina. PhotographCREDIT: © Alan Karchmer/Esto. All rights reserved.

Puente de la Mujer, Buenos Aires, Argentina. PhotographCREDIT: © Alan Karchmer/Esto. All rights reserved.The Millennium Bridge crosses the Thames without a lot of fuss, but many contemporary footbridges are called upon to be instant landmarks, much like iconic buildings. No one has built more landmark bridges than Spanish architect-engineer Santiago Calatrava. This footbridge crosses over the Rio de la Plata in the port of Buenos Aires. The 525-foot walkway is supported by stay cables strung from a dramatic steel pylon like harp strings. The swing bridge rotates 90 degrees, in order to permit river traffic to pass. As in many of Calatrava's structures, this sculptural solution is not as straightforward as it first appears. Since the mast is leaning over the deck, the open bridge is inherently unbalanced. To support the weight of the bridge, the portion of the hollow pylon beyond the swivel point is filled with concrete and acts as a hidden counterweight.

-

Newport City Footbridge, Newport, United Kingdom. Photograph by Richard Scott-Smith, licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. Courtesy CREDIT: www.wikipedia.org.

Newport City Footbridge, Newport, United Kingdom. Photograph by Richard Scott-Smith, licensed per Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike. Courtesy CREDIT: www.wikipedia.org.This footbridge over the River Usk in Newport, Wales, designed by Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners and the Atkins engineering group, is another example of a dramatic cable-stayed bridge that is the centerpiece of an urban renewal project. The cables carrying the 229-foot span are supported by two A-frame masts that stand on one bank. The frames, in turn, are stayed by two massive 4¾-inch-diameter cables. Landmark bridges often resemble free-standing sculptures; this one recalls the marine cranes that once unloaded sailing ships on the Newport wharves.

-

Crow Creek Bridge, Tulsa, Okla. Photograph courtesy Bing Thom Architects.

Crow Creek Bridge, Tulsa, Okla. Photograph courtesy Bing Thom Architects.This unusual cable-stayed footbridge, designed by Bing Thom Architects of Vancouver, British Columbia, with engineers Fast & Epp, will be the gateway to the Crow Creek Redevelopment, a new district of restaurants, shops, and entertainment venues along the banks of the Arkansas River in Tulsa, Okla. The span is not large—only 100 feet—but the effect is of extreme lightness. The wooden deck is carried by wires, like a suspension bridge, but instead of a supporting cable, thin individual wires lead back to a cluster of turned-log masts on each bank. The wooden deck is intended to flex slightly as people walk across.

-

Gatwick Pier Six Air Bridge, London. Photograph courtesy Nick Wood and Wilkinson Eyre Architects.

Gatwick Pier Six Air Bridge, London. Photograph courtesy Nick Wood and Wilkinson Eyre Architects.One of the longest recent footbridges is not a landmark but a functional way to get passengers over a taxiway at London's Gatwick Airport. The glass-enclosed bridge had to be high enough to clear a Boeing 747-400 jumbo jet, but the real challenge was the fact that the busy taxiway could not be closed for long during construction. The 657-foot framed arch truss was prefabricated outside the airport and transported one mile to be hoisted into place over a period of only 10 days. The award-winning design is the work of Arup, with architects Wilkinson Eyre.

-

BP Pedestrian Bridge, Millennium Park, Chicago. Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.

BP Pedestrian Bridge, Millennium Park, Chicago. Photograph by Witold Rybczynski.The BP Bridge spanning Columbus Avenue and linking Chicago's Millennium Park with the lakefront takes bridge design in a different direction. Frank Gehry had participated in the 1996 competition for London's Millennium Bridge, and his bridge in Chicago is equally whimsical. The sinuous shape and the overlapping stainless-steel scales give the bridge a vaguely reptilian appearance, though why a bridge should look like a snake is unclear (Gehry once designed a building in the form of a fish). The shape is pleasing, and the Brazilian-wood deck is attractive, but the design lacks the lift and airiness that one associates with the best footbridges; this is styling rather than engineering.

-

Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, Minneapolis, Minn. Photograph © Chris Gregerson.

Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, Minneapolis, Minn. Photograph © Chris Gregerson.At least Gehry's bridge has a consistent aesthetic. In the mid-1980s, the Walker Art Center commissioned local artist Siah Armajani to design a 379-foot-long bridge linking the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden with Loring Park. The combination of trestle, arch, and suspension bridge is unconvincing and makes little structural sense. Bridges may sometimes be artful, but they should never try to be arty.

-

At first glance, the 266-foot-long footbridge across the Rio Mondego in central Portugal looks like one of those classic concrete bridges designed in the early 1900s by the great Swiss bridge engineer Robert Maillart. But it isn't, quite. The two halves of the bridge are asymmetrical and push against each other where they meet in the center. The design, by Cecil Balmond of Arup, António Adão da Fonseca, and AFAssociados, is both ingenious and, with its central kink, somewhat contrived. As for the balustrades of colored glass, well, sometimes too much is just too much.

-

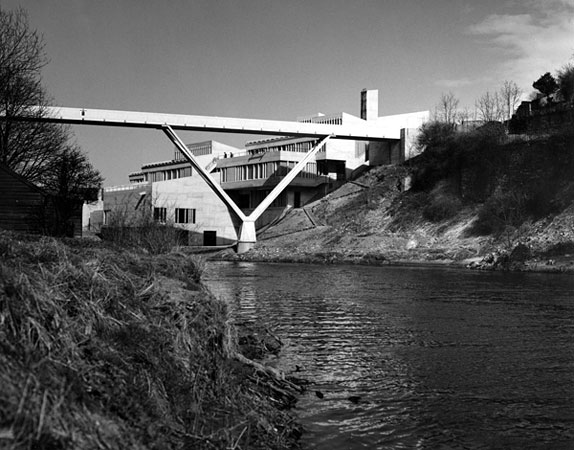

Kingsgate Bridge, Durham, United Kingdom. Arup Associates. Photograph courtesy Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Kingsgate Bridge, Durham, United Kingdom. Arup Associates. Photograph courtesy Architectural Press Archive/RIBA Library Photographs Collection.The British engineering firm Arup has been responsible for many of today's most interesting bridges. Arup was founded by Ove Arup (1895-1988), a Danish engineer who immigrated to Britain, and who collaborated with many notable architects on buildings such as Coventry Cathedral and the Sydney Opera House. Arup also designed a footbridge himself, and it's a beaut. The problem was to span the River Wear, linking two parts of the University of Durham. The budget of £35,000 (in 1961) was barely sufficient to build a short, 120-foot bridge at the bottom of the valley. Undaunted, Arup proposed a bridge whose deck was at the level of the top of the valley, even though this meant a span three times greater. To avoid building expensive formwork across the valley, the two halves of the concrete structure, supported by four slender fingers, were cast in place on the two banks, then swiveled 90 degrees to connect in the middle. Ingenious, inexpensive, and handsome—everything a good bridge should be.