Theodate Pope's Pioneering Architecture

-

Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.

Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.Only one of the 29 winners of the annual Pritzker Architecture Prize has been a woman. This is a reflection of the fact that only in the last few decades have large numbers of women entered what was traditionally a man's field. Which makes the three American women architects who achieved prominence at the turn of the 19th century that much more remarkable. Julia Morgan (1872-1957), a trained engineer and the first woman (of any nationality) to graduate from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, built William Randolph Hearst's San Simeon and scores of other interesting buildings. Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter (1869-1958) was a talented regionalist, responsible for a series of striking structures in the vicinity of the Grand Canyon. Theodate Pope (1867-1946) was the most original. Almost entirely self-taught, she came to architecture slowly. Her first commission, at 31, was a country house for her parents in Farmington, Conn. Today, Hill-Stead is considered one of the leading examples of Colonial Revival architecture.

-

Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.

Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.Pope was imperious and strong-willed—not bad qualities for an architect—but at the time of designing Hill-Stead, her only experience was the renovation of her own cottage. Her father, a wealthy Cleveland industrialist, suggested that she needed help with the house, and steered her to McKim, Mead, and White, who were building a country house for his business partner. She agreed, but made it very clear who would be in charge. "I expect to decide all the details as well as all more important questions of plan that may arise," she wrote to William Mead. "This must be clearly understood at the outset, so as to save unnecessary friction in the future. In other words, it will be a Pope house instead of a McKim, Mead and White." And a Pope house it is. Despite the monumental Mount Vernon porch, it is really a grand rambling farmhouse, with a long tail of attached outbuildings and barns.

-

Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson. Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.

Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson. Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.The public rooms of Hill-Stead have the openness of Frank Lloyd Wright's contemporaneous Ward Willits house. On the walls of the unusual L-shaped living room hang paintings by Monet, Degas, Whistler, and Cassatt, part of Alfred Pope's outstanding collection of Impressionist artists. Henry James visited the house and compared it to "the momentary effect of a large slippery sweet inserted, without a warning, between the compressed lips." Hill-Stead has none of Stanford White's eclectic theatricality or Charles McKim's geometrical order. Instead, like its Colonial forebears, the house is resolutely—and sweetly—comfortable, made up of domestic bits and pieces, bay windows and porches, chimneys and dormers, but amplified to a larger scale. McKim, Mead, and White went along with all Pope's suggestions, and thought well enough of the project to illustrate it in their famous 1915 monograph (which includes few country houses), but they did not credit her as its designer.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.After Hill-Stead, it would be almost another decade before Pope embarked on a full-fledged architectural career. Her oeuvre is not large: a handful of country houses in Connecticut, a large estate on Long Island, the rebuilt birthplace of Theodore Roosevelt in Manhattan, and three schools. The first of these was Westover School. The girls school, completed in 1909, was contained in a single large building that faces the village green of Middlebury, Conn. The gymnasium, dining hall, library, and assembly hall, as well as classrooms and students' rooms, were arranged around a courtyard landscaped by Beatrix Jones Farrand. The style of the building is Colonial Revival, although unlike most examples, it is made of plastered concrete. (Hill-Stead is fireproof concrete, too, beneath the wood siding.) Pope domesticated the 270-foot-long facade by introducing a houselike form over the central entrance. The tall roof, as well as the squat cupola that contains the school bell, emphasizes the domestic appearance.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.The facade of the center block is long and absolutely symmetrical. Two dissimilar protruding wings contain the headmistress's residence at one end and the chapel at the other. While the style of the building is Colonial Revival, that of the chapel is Gothic. This is a daring move that few architects would attempt. It works here, as it creates the impression of a building that has been added to over the years, yet manages to avoid the cloying picturesqueness of a historical simulation. "I am tired of seeing these fluted flimsy highly colored hen houses going up," Pope once wrote of contemporary architecture. There is nothing flimsy about this solid-looking building.

-

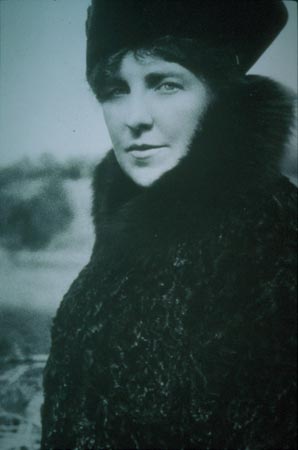

Theodate Pope Riddle, 1915. Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.

Theodate Pope Riddle, 1915. Image courtesy Hill-Stead Museum, Farmington, Conn.The demands of the profession—as well as personal choice—kept both Julia Morgan and Mary Colter single. Theodate Pope married late in life (at 48) to John Riddle, a career diplomat. It was an unconventional marriage—Riddle was ambassador to Argentina, while Pope pursued her own career (under her maiden name)—but she was an unconventional woman. Though wealthy, Pope was an avowed socialist and a suffragette; though a devotee of Arts and Crafts, she owned a Stutz Bearcat. She suffered from bouts of depression but was tough enough to survive the wartime sinking of the Lusitania. (Pope jumped into the ocean, lost consciousness, and was rescued after several hours in the water.) She had a wide circle of friends: Henry James, William James (with whom she shared a passionate interest in spiritualism), Mary Cassatt, architectural critic Marianna van Rensselaer, Franklin D. Roosevelt, John Dewey, and Charles W. Elliot of Harvard. With the last two she exchanged ideas on education.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.The project that consumed the last two decades of her life was founding and building her own preparatory school for boys. For Avon Old Farms School, in Avon, Conn., Pope devised the (nondenominational) curriculum, an original blend of progressive academics, hands-on learning, and old-fashioned rectitude. She replaced athletics—there would be no gymnasium—with farm chores. (The first sport she finally allowed was, characteristically, polo.) Manual crafts were emphasized. A craft tradition informed the construction of the buildings, too. Impressed by the English rural buildings she had seen on her travels and influenced by the writing of William Morris, Pope imported craftsmen from the Cotswolds, and in 1921 she set about creating a campus that included carpentry shops, a forge, and farm buildings. The tall brick structure is not a silo but a water tower. Beyond the academic quad was a sort of village, with the headmaster's house, general store, post office, and—lest the boys forget that they were living in a capitalist society—a bank. To emphasize its nonacademic role, the bank has a classical Doric portico.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.At the height of construction, more than 500 workers labored away using 17th-century techniques: pegging oak frames, forging strap hinges, and laying slates. Despite the atmosphere of Tudor picturesqueness—Hogwarts before the fact—Avon is not a stage set. For one thing, the place is too real. Pope intended the school to be "indestructible," and to that end everything was robustly dimensioned: massive doors, heavy flagstone floors, ponderous hardware. For another, it's all done with a great deal of conviction. A stage set makes you think of the "real thing"; Avon may be quirky, yet it is no facsimile, but resolutely itself.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.Avon opened in 1927, one year after that other visionary school, Walter Gropius' Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany. Pope was well aware of Modernism. The famous exhibition on the International Style at the Museum of Modern Art—which helped to establish architectural Modernism in the United States—was organized by her cousin Philip Johnson. When the exhibition traveled to Hartford, Pope was invited to participate in an accompanying symposium. She said that she considered Modern architecture a failure, because it was purely intellectual and ignored the emotions. "Men who work with machinery during the day might rather not sleep in a machine at night," she observed.

-

Image courtesy the author.

Image courtesy the author.Unlike the defunct Bauhaus, Avon continues Pope's educational vision today. (It closed briefly in 1944 but resumed operations in 1948.) The boys still wear jackets and ties, though no longer the uniforms once specially made for them by Brooks Brothers. They still live in tiny rooms that resemble ships' cabins and attend classes in low-ceilinged parlors (though these are now hard-wired). The original chalkboards are still there, but they're augmented by digital flat screens. The students still eat lunch and dinner together in the immense beamed dining hall, sitting on wooden benches, the masters at the head of the long tables serving out the plates to their charges. The boys also politely address visiting architecture critics, "Good morning, sir." Pope would have liked that.