The Golden Age of Skyscrapers

-

Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Cesar Pelli and Associates). Photograph © Jeff Goldberg/Esto.

Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Cesar Pelli and Associates). Photograph © Jeff Goldberg/Esto.Immediately after 9/11, there was widespread speculation that the destruction of the World Trade Center heralded the demise of the tall building. Not so. Five years later, skyscrapers continue to be built in cities around the world. Moreover, skyscraper design itself is undergoing a major evolution. The classic towers of the 1920s took their cue from spires and steeples—they stepped back as they rose (the Empire State Building) and ended in a pinnacle (the Chrysler Building). Modernist skyscrapers, such as the boxy Seagram Building, abandoned the steeple model. Postmodern architects resurrected the spire-top, although they usually combined it with a more-or-less standardized shaft, as in the twin Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur (at right). But even before 9/11, there were signs that new types of skyscrapers were emerging, neither Modernist boxes nor replays of the spire model.

-

Hearst Building, New York (Foster and Partners with Adamson Associates). Image courtesy Foster and Partners.

Hearst Building, New York (Foster and Partners with Adamson Associates). Image courtesy Foster and Partners.The first architect to radically rethink the skyscraper was Norman Foster. At the time—1986—critics hailed his headquarters for the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank as an example of the so-called high-tech style. But later skyscrapers such as the Century Tower in Tokyo and the Commerzbank in Frankfurt show that Foster and Partners is interested in much more than merely exposing structure. They want to reconsider how skyscrapers are built. The Hearst Building (at right), now nearing completion in New York, is a good example. It somewhat resembles a Brancusi sculpture, but the unusual crystalline form, or "diagrid," as the architects call it, has a functional purpose: Thanks to the diagonal bracing, the building uses 20 percent less steel than a conventional structure. If Buckminster Fuller, one of Norman Foster's mentors, had designed a skyscraper, it would have looked something like this.

-

Swiss Re, London (Nigel Young/Foster and Partners). Photograph courtesy Foster and Partners.

Swiss Re, London (Nigel Young/Foster and Partners). Photograph courtesy Foster and Partners.The 40-story London headquarters of Swiss Re, completed in 2004, is even more unusual. Foster and Partners' conical tower has been nicknamed the Gherkin, although to me it looks more like a Jules Verne rocket ship. (There is a private dining room in the nose cone.) The circular plan and tapering cross-section reduce wind loads on the building and also decrease gusting at street level. The tower is divided into six-story sections, incorporating interior light wells and "sky gardens," which were first introduced at the Commerzbank. The result is not merely a striking building but also a more comfortable and energy-efficient work environment. Swiss Re is probably the most technologically advanced office tower in the world today.

-

Torre Agbar, Barcelona, Spain (Ateliers Jean Nouvel with b720 arquitectos). Photograph © El Pais Photos.

Torre Agbar, Barcelona, Spain (Ateliers Jean Nouvel with b720 arquitectos). Photograph © El Pais Photos.Barcelona's 31-story Torre Agbar superficially resembles Swiss Re, but it's really a very different sort of skyscraper. "This is not a tower," architect Jean Nouvel has said. "It is not a skyscraper in the American sense of the expression: It is a unique growth in the middle of this rather calm city. But it is not the slender, nervous verticality of the spires and bell towers that often punctuate horizontal cities. Instead, it is a fluid mass that has perforated the ground—a geyser under a permanent calculated pressure." This overwrought description reflects Nouvel's approach to design, which can be almost operatic. While Foster uses technology to solve problems, in Nouvel's buildings technology is at the service of architectural—usually sensual—effects. The Barcelona tower is a reinforced concrete silo. Not for reasons of energy conservation or security, but so that it can be wrapped in glass-louvers, whose chief function, as far as I can tell, is to create the shimmering effect of a "geyser."

-

Brickell Flatiron, Miami (Taller de Enrique Norten Arquitectos). Image courtesy TEN Arquitectos.

Brickell Flatiron, Miami (Taller de Enrique Norten Arquitectos). Image courtesy TEN Arquitectos.Where the Torre Agbar is hot, the 70-story Brickell Flatiron in Miami is cool. Its name recalls Daniel Burnham's famous Flatiron Building in New York, which occupies a similar triangle-shaped site. But Enrique Norten's design owes nothing to the past. The rounded form reduces wind loads—Hurricanes Katrina and Wilma blew out hundreds of windows in Miami high-rises—and the streamlined result is sleekly sculptural, especially in the top portion of the building, which contains apartments. The bulkier lower floors house offices, parking, and shops.

-

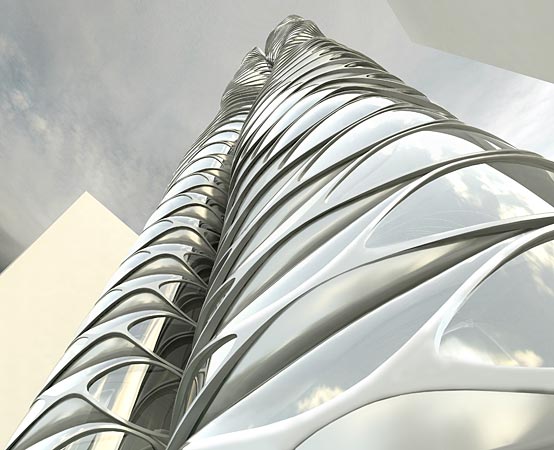

Residential Tower, Dubai, UAE (Ali Rahim and Hina Jamelle/Contemporary Architecture Practice). Image courtesy Contemporary Architecture Practice.

Residential Tower, Dubai, UAE (Ali Rahim and Hina Jamelle/Contemporary Architecture Practice). Image courtesy Contemporary Architecture Practice.Digital architecture, as it's sometimes called, represents not merely a technique for producing forms using computer software, but a particular visual taste. It is best summed up by the word "seamless." Everything morphs into everything else: floors, walls, columns, beams, structure, furniture. This approach owes something to early German Expressionists such as Eric Mendelsohn, and to Eero Saarinen (in his TWA mode). So far, the much-ballyhooed digital revolution in architecture has produced many long essays and a few short buildings. That will change when the 45-story residential tower (at right), designed for Dubai by Ali Rahim and Hina Jamelle of Contemporary Architecture Practice, is built. Their challenge will be to translate the pristine computer-generated image into real-life messy building materials.

-

Turning Torso, Malmö, Sweden (Santiago Calatrava SA). Photograph © Barbara Burg + Oliver Schuh, www.palladium.de.

Turning Torso, Malmö, Sweden (Santiago Calatrava SA). Photograph © Barbara Burg + Oliver Schuh, www.palladium.de.Ever since William Van Alen concocted the Chrysler Building, skyscrapers have served as icons, instantly recognizable symbols of a corporation—or a place. That is the market force driving the current generation of eye-catching towers. When the small Swedish city of Malmö wanted to get on the map, it brought in Santiago Calatrava to build an unusual 54-story apartment tower. The form is a Modernist box that has been torqued 90 degrees from top to bottom. Calatrava is an engineer-architect, but this has little to do with construction—it's Art. In case you miss the point, the building has a portentous title: Turning Torso.

-

Museum Plaza, Louisville, Ky. (Office for Metropolitan Architecture). Image courtesy Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

Museum Plaza, Louisville, Ky. (Office for Metropolitan Architecture). Image courtesy Office for Metropolitan Architecture.Louisville wants an icon, too. The recently unveiled design for Museum Plaza rises 61 stories, though it's not exactly a skyscraper. Joshua Prince-Ramus, the head of Office for Metropolitan Architecture Office for Metropolitan Architecture's New York operation, has likened it to a chair. "One leg will contain the hotel, another lofts, the third a vertical elevator, the fourth the angled glass elevator. Two towers will have luxury condos, the third an office tower." The seat of the chair, more than 20 stories up in the air, houses a museum of contemporary art. This spectacular composition will dominate Louisville's skyline, which also includes (at right) one of the last 1960s-era gridded boxes to come from the office of Mies van der Rohe—sandwiched here between Philip Johnson and John Burgee's domed neoclassical tower and Michael Graves' controversial Postmodern icon, the Humana Building, now looking rather tame.

-

New York Times Building, New York City (Frank O. Gehry & Associates in association with David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill). Image courtesy Gehry Partners, LLP.

New York Times Building, New York City (Frank O. Gehry & Associates in association with David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill). Image courtesy Gehry Partners, LLP.Some skyscraper designers are taking another, very different direction, and it appears first in the work of that great iconoclast, Frank Gehry. In the summer of 2000, Gehry took part in an invited competition for the new headquarters of the New York Times. He had never built a skyscraper, which may be why he teamed up with David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. The Gehry/Childs 45-story tower is roughly square in plan, but the top erupts into sculptural mayhem that vaguely recalls the Times' logo. The effect is nothing like a spire; it's more a jack-in-the-box. Halfway down, the façades peel away from the building and slip to the sidewalk in rumpled confusion. This proposal was never built—Gehry withdrew from the competition—yet, for many architects, his unfettered design pointed toward a new way to think about tall buildings. Pandora's Box has been opened.

-

Fiera Milano, Milan (Zaha Hadid Architects, Arata Isozaki & Associates, Studio Daniel Libeskind, Pier Paolo Maggiora). Image © Stack!

Fiera Milano, Milan (Zaha Hadid Architects, Arata Isozaki & Associates, Studio Daniel Libeskind, Pier Paolo Maggiora). Image © Stack!The sense that the old rules no longer apply is evident in this trio of office buildings in a prize-winning proposal for the old Fiera Milano site in Milan. Arata Isozaki's saillike form, on the right, appears to be a relatively conventional interpretation of the Modernist slab, until you notice the odd-looking props at the base. The skewed planes of Zaha Hadid's twisted tower on the left, while more elegant than Calatrava's, have the same forced structural logic. So does Daniel Libeskind's bowing, curving skyscraper. (Since elevators move in straight lines, there is a freestanding elevator core, just visible in the rear.) As new as this may be, it all feels a little forced. Being iconic is getting harder all the time.