The End of Gerrymandering

Have California’s citizen commissions killed corruption in congressional redistricting?

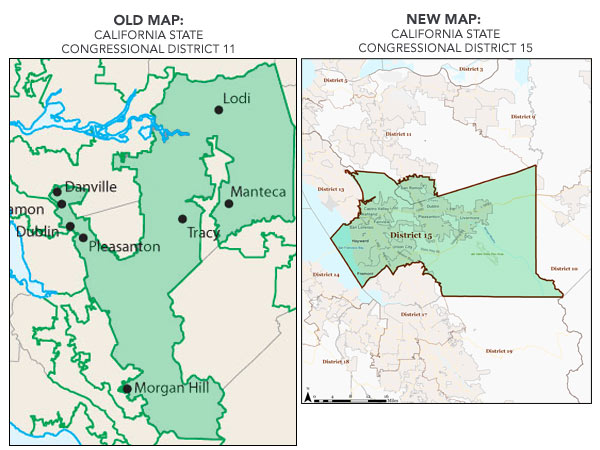

California’s 11th congressional district is green and gently hilly, home to affluent East Bay suburbs like Danville and Dublin. It is also golden and craggy, encompassing a mountainous state park overlooking San Jose, two counties and 60 miles to the south. And it is flat, hazy, and redolent of manure, since it also snakes far into the agricultural Central Valley to take in cow towns like Tracy and Lodi. (Yes, that’s the same Lodi that Creedence Clearwater Revival was always getting stuck in.)

What’s odd about the district isn’t its size—it’s right around the median of the country’s 435 congressional districts in total land area. Rather, it’s the sprawling, three-tendril shape, which has been described as resembling a claw or a hammerhead shark. It also resembles a Rorschach inkblot, which is appropriate: Legislators look at it and see a perfectly valid congressional district, while the average citizen sees an abomination.

The problems with gerrymandered districts such as California’s 11th seem obvious. Drawn by incumbents with the goal of protecting incumbency, they stifle competition, reward corruption, and can leave minorities underrepresented (or, in a few cases, overrepresented). In effect, they allow representatives to choose their voters, rather than the other way around.

After decades of throwing up their hands at state lawmakers’ redistricting shenanigans, California’s citizens recently took the process into their own hands. A proposition on the 2008 ballot set up an independent commission to draw new state legislative and congressional district boundaries following the 2010 census. After a thorough application process followed by a lottery, five Democrats, five Republicans, and four independents won the chance to spend hundreds of hours poring over census data and fielding public input in hopes of reshaping the Fightin’ 11th and other, equally grotesque-looking districts up and down the state.

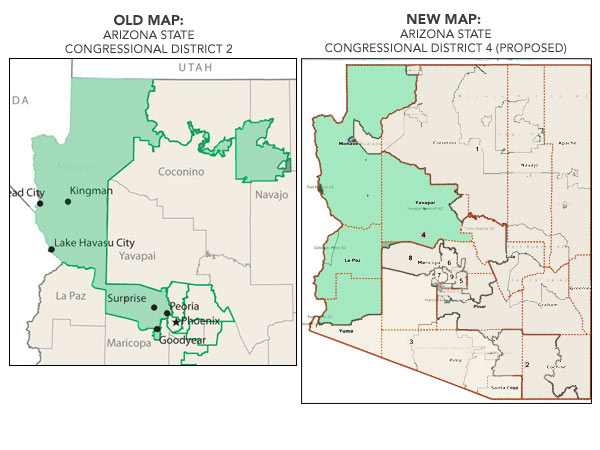

California isn’t alone in relieving its legislative foxes of their henhouse-guarding duties. Several other states, including Arizona, Hawaii, and New Jersey, have set up independent commissions to draw their district maps. Some have even invited members of the general public to try their hand, using online tools that allow you to see instantly how your changes will affect a district’s demographics. Students in a law seminar on redistricting at Columbia University have used geographic information system software to propose new maps for all 50 states. (You can try it yourself here and here.)

So have the new citizen-technocrats managed to cleanse the redistricting process of partisan politics and craven self-interest? Have their efforts been hailed far and wide for their fairness and rationality?

Not really, but that’s not for lack of merit.

In Arizona, whose commission comprises two Democrats, two Republicans, and one independent who serves as chair, the partisan members deadlocked and the independent broke the tie in favor of the Democrats’ plan. Republican Gov. Jan Brewer responded by impeaching the chair. (The state Supreme Court later reinstated her.)

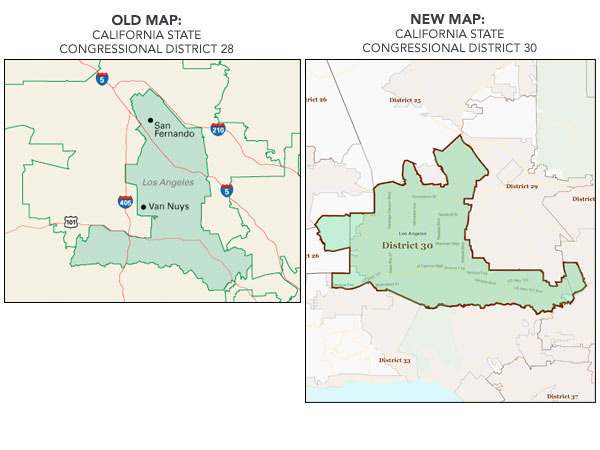

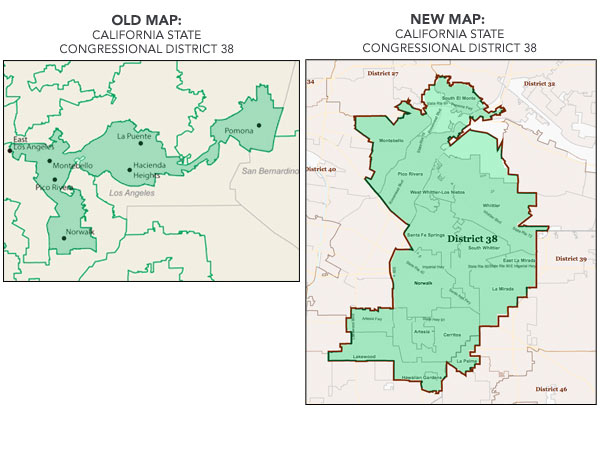

California’s process avoided the tiebreaker pitfall by requiring bipartisan agreement among its commission members. Impressively, they achieved it, approving new maps unanimously. But that didn’t stop Republicans, and some minority groups, from crying foul. Republicans allege that three Southern California districts were rigged to protect Democratic incumbents; some Latinos have complained that the new maps don’t include enough Latino-majority districts. With no gerrymandering legislators to blame, Republicans resorted to criticizing a nonpartisan consultant from UC-Berkeley who helped draw the maps. (“I had never been called a ‘partisan hack’ in my life” before consulting on the redistricting project, the consultant, Karin Mac Donald, told me.) Republican activists filed two lawsuits challenging the redistricting plan in the state Supreme Court. After losing both, they recently reloaded with a new federal suit. Meanwhile, another group of Republicans has raised millions in a bid to put the new maps to a referendum.

As for the various state contests that invite average citizens to submit their own plans, they’ve proven to be mostly for show. No state has yet adopted an outsider’s plan, even though many have been objectively superior to the real maps on criteria such as competitiveness and compactness. A college student won a Michigan redistricting competition this summer with a computer-generated plan that is significantly cleaner than what the lawmakers in Lansing conjured. They ignored it, of course.

The independent commissions, meanwhile, seem to be working, in spite of what the vicious fights in California and Arizona might suggest. If anything, those battles are a signal that the new commissions are working too well for some people’s comfort.

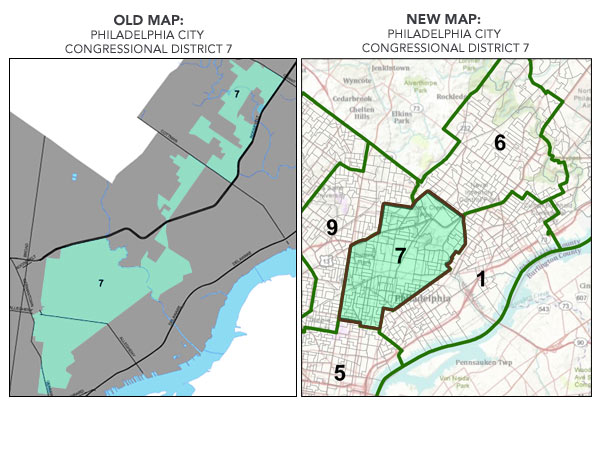

Often, congressional gerrymanders are the result of bipartisan compromise—an agreement that allows the majority party to solidify its hold on the state while throwing bones to the minority party’s incumbents. (An online redistricting game that lets you draw lines in a fictional state gives a great feel for how this plays out.) That’s how the byzantine shape of California’s old 11th district came about. Democrats excised the liberal stronghold of Stockton from what was then Republican Rep. Richard Pombo’s district to bolster one of their own. In exchange, they let Pombo’s district snake into a neighboring valley to pick up Republican-leaning suburbanites. The Democrats were happy, and Pombo had no complaints, as his new constituents were presumed to have deep pockets.

Such back-scratching was absent from the citizens redistricting commission’s process. It dispensed with the old maps entirely, drawing new districts that look less like abstract doodles and more like, well, districts. One result is that Democrats appear poised to pick up a few seats in California in 2012, assuming the new maps stand. Another is that some unlucky incumbents, including Democrats, have been drawn out of their own districts—a grim fate normally reserved only for those who have egregiously offended higher-ups within their own party as well as the opposition. The prominent Southern California Democrats Brad Sherman and Howard Berman, for instance, have been thrust into the same district, setting up a costly Berman/Sherman primary showdown. No wonder the commission has taken heat from all sides.

Arizona’s commission actually had an explicit mandate to promote competition between parties, almost assuring that its plans would meet resistance. It threatens to upset the current 5-3 Republican House majority with a map that leaves four seats safe for the GOP, two for the Democrats, and three up in the air.*

Cutting out the partisan horse-trading doesn’t make redistricting any easier. Compliance with the Voting Rights Act, which requires fair representation for minorities, can be tricky. Then there are disagreements over what, exactly, makes for a good district. Is it more important to keep the lines clean, to foster competition, or to abide by natural boundaries? There are so many factors to take into account that even seasoned mappers can overlook important features. Nathaniel Persily, who teaches the Columbia law seminar on redistricting, recalls helping to draw up new lines for New York only to be confronted by an unhappy Rep. Anthony Weiner (in the pre-Weinergate days). Weiner was miffed that Persily had cut an unpopulated swamp out of his district. To Persily’s computers it made no difference, but Weiner pointed out that he had important environmental projects going on there.

Still, the experiments of states like California and Arizona show that, if nothing else, citizen commissions can draw lines that look and feel fairer than what state lawmakers tend to come up with. If the results hold up in court, both states are likely to see more contested races in 2012 than they have in years past. And despite the hassle and inevitable backlash, other states will probably follow suit. Eventually best practices will evolve and take root.

While the decline of gerrymandering would be welcome, it won’t keep the country’s politicians from finding ways to choose their voters. They may just have to work a little harder. Jerry McNerny, the Democrat who replaced Richard Pombo in California’s 11th, was one of those drawn out of his district by the citizens commission. No problem: He announced shortly after the maps were unveiled that he’d be picking up stakes and following his district eastward. His explanation: “After spending so much time in San Joaquin County, it truly is my home.”

Correction, Dec. 19, 2011:This story originally miscounted the number of seats considered safe for Republicans in the latest draft of Arizona's congressional redistricting maps. Four of nine total seats are presumed safe for the GOP, not two of seven. (Return to the corrected sentence.)