How Campaigning for President Became a Socially Acceptable Thing to Do

-

Painted by T.H. Matteson, engraved by H.S. Sadd/Library of Congress.

In the early days of the presidency, no man worthy of the office would have dared campaign for it. Now, as I write in my series How to Measure for a President, the strength of a candidate’s campaign is used as proof of his fitness for office. Here, with the help of Gil Troy’s See How They Ran is a tour of how we got here.

George Washington and his compatriots would never have trusted a man who actively sought the presidency. First Viscount Bolingbroke, a key intellectual source for the Founders, wrote that "a patriot king,” in a republic “was above faction and party and governed in the interests of the entire nation rather than carrying out the desires of narrower interests." When Washington responded to the letter announcing his unanimous selection, he wrote that he had “concluded to obey the important and flattering call of my Country.” Future generations would try to maintain this ambition-free posture while privately plotting and planning for high office.

Pictured: Washington delivering his inaugural address in April 1789, in the old City Hall, New York. -

Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts.

The election of 1800, the third in the nation’s history, proved that nastiness is in our heritage. The candidates did not advocate for themselves, but in a foreshadowing of the super PAC, their political parties and allies savaged the other side on their behalf. In this cartoon, Jefferson kneels before the altar of Gallic despotism as God and an American eagle attempts to prevent him from destroying the U.S. Constitution. He is depicted flinging a document labeled "Constitution & Independence U.S.A." into the fire. Jefferson was referred to as “a mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father,” wrote one Federalist. Another newspaper warned that if Jefferson were elected "murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood." Jefferson’s opponent, John Adams, was called “a blind, bald crippled toothless man" who imports mistresses from Europe and possessed a "hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman."

Pictured: The Providential Detection depicts Jefferson attempting to destroy the Constitution. Artist unknown. 1797-1800. -

Painted by Thomas Sully/Library of Congress.

In the election of 1828, Andrew Jackson was the first candidate to claim popular endorsement by the people. His election was called “the rise of the common man” and as a result, he declared that, contrary to tradition, he owed the people some account of his policy positions. "It is incumbent on me, when asked, frankly to declare my opinions upon any political or national question pending before and about which the country feels an interest." Jackson wasn’t campaigning for office per se, but he did help establish the connection between the people and the selection of their president. The election of 1828 also saw an escalation in personal attacks. The “Coffin Handbills” accused Jackson of murdering several deserters during the War of 1812.

Pictured: Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson, president of the United States, around 1820, Philadelphia. -

Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images.

Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images.The election of 1840 saw the birth of a number of campaign techniques we would recognize today. Though William Henry Harrison was born to great wealth, a team of spin doctors portrayed him as a man of the frontier, a sign that popular opinion was starting to creep into the presidential contest. In 1836, Kentucky Rep. Sherrod Williams demanded that the presidential candidates answer questions about where they stood on certain questions and in a nod to these demands, William Henry Harrison’s “correspondence committee” issued the first press release about his positions. His campaign also offered one of the first slogans, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,” referring to Harrison’s victory at the battle that took place at Tippecanoe, Ind., and his vice presidential nominee. The phrase “keep the ball rolling,” originated during this campaign from a gigantic canvas ball Harrison’s supporters rolled across the country in support of his effort.

Pictured: Presumably D.E. Brockett in 1888 leaning against a gigantic campaign ball rolled for Benjamin Harrison. The phrase "get the ball rolling" comes from a campaign publicity activity that began in 1840 with rowdy men and boys rolling a large ball from town-to-town to bring attention to their candidate. -

Currier & Ives/Library of Congress.

Though a candidate’s supporters could whip up the crowds for him, it was still considered bad form for a candidate to openly campaign too much. In 1860, Stephen Douglas pretended that he was on a trip to visit his mother in order to cover up his political campaigning. A political cartoon poked fun of him and the notion of going out on the “stump.” “Gentlemen, I’m going to see my mother,” Douglas says in the cartoon, “and solicit a little help for in running after a nomination.” Lincoln is depicted leaning on the fence saying “stumping won’t save you.”

Pictured: "Taking the stump" or Stephen in search of his mother, around 1860. A satire on Douglas's July 1860 campaign tour of upstate New York and New England. -

Library of Congress.

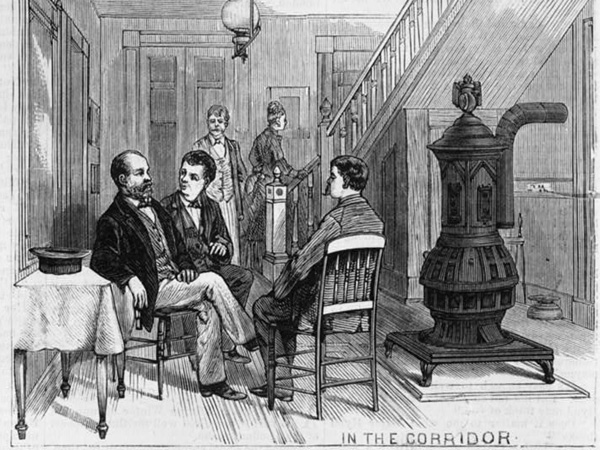

Library of Congress.James Garfield ran the first successful “front porch” campaign in 1880, running for office from his home, which often meant greeting well-wishers on his front porch. Garfield’s advice was to "sit crossed legged and look wise until after the election.” In a cabin elsewhere on his property, his campaign office contained a telegraph that delivered the news that he had won one of the closest elections in the nation’s history. In 1888, Benjamin Harrison ran his own front-porch campaign, and in 1896 William McKinley perfected the technique.

Pictured: In the corridor of James A. Garfield's home, at Mentor, Ohio, wood engraving, 1880. -

Library of Congress.

In 1896, William McKinley’s front-porch campaign contrasted with the arrival of the modern stump speech performed by his voluble rival William Jennings Bryan. When a Bryan supporter bragged that he gave 19 speeches a day, an opponent asked, “When does he think?” Bryan, a three-time loser as a Democratic presidential candidate, was also the first candidate to campaign by car.

Pictured: William Jennings Bryan delivers a campaign speech, July 3, 1908. -

George Luks, lithograph, Published in CREDIT: The Verdict, March 13, 1899.

McKinley’s campaign manager, Mark Hanna, is considered the first great political Svengali to orchestrate the action behind the scenes. The two men had been plotting to take the office for at least four years before the election, a long way from the standard Washington set 100 years earlier. Hanna prepared the way for other political men who became famous like FDR’s Louis Howe, Bush’s Lee Atwater, Clinton’s James Carville, Bush’s Karl Rove, and Obama’s David Plouffe. Hanna is also credited with deploying vast wealth to win an election. Presidents still didn’t campaign for the job, but to combat Bryant’s campaign, which criss-crossed the nation, Hanna hired an army of 1,400 campaign workers and enlisted surrogates to campaign in targeted areas.

Pictured: The infamous Republican Party boss "Dollar" Mark Hanna sneering to McKinley, "That Man Clay Was an Ass. It's Better To Be President than to be Right!" -

Western History/Genealogy Dept., Denver Public Library via Library of Congress.

Western History/Genealogy Dept., Denver Public Library via Library of Congress.In 1932, FDR flew a plane to the Democratic Party Convention. Not only was this a risky use of the new mode of transportation, but it also destroyed an obsolete tradition. Candidates had waited to be informed of their party nomination in a “notification ceremony,” a vestige of the tradition of selecting men who didn’t campaign. But the pick was no longer a surprise, so FDR ended the charade by showing up in person at the convention. “You have nominated me and I know it,” he said. “And I am here to thank you for the honor.” In 1936, Roosevelt would do away with another nicety, defending his office while still in it. His cousin Teddy had lamented in 1904, “I have continually wished that I could be on the stump myself. … I have fretted at my inability to hit back, and to take the offensive.” FDR did hit back, using radio and public opinion polls extensively.

Pictured: Colorado Go. William H. "Billy" Adams rides with Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt on his visit to Denver, Colo., on the campaign trail for the president. They are leaving Union Station in a automobile caravan or parade. -

CREDIT: Photo by Thomas D. Mcavoy/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

CREDIT: Photo by Thomas D. Mcavoy/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.In 1948, Harry Truman launched a whistle-stop train tour to defend his presidency. He still had to maintain the fiction, as President Obama does today, that the trip he was taking was for official business. It was a hard act to keep up though, and eventually Truman let everyone know he was in on the joke. Never before had an incumbent worked so hard to keep the office.

Pictured: President Harry Truman, with wife Bess and daughter Margare, waving from train during whistle-stop at Pocatello, Idaho, June 1948. -

YouTube still.

In 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was the first presidential candidate to air a television commercial. Awkward and often staring off-

Pictured: A 1952 televised commercial featuring Dwight Eisenhower. -

Photo by Joseph Scherschel/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

Photo by Joseph Scherschel/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.The 1960 Kennedy vs. Nixon debates are perhaps the most iconic moment of the modern presidential campaign. Kennedy, who was a far less experienced politician than Nixon, appeared impressive on television. By 1960, approximately 90 percent of American homes had televisions, and an estimated 70 million people watched the first contest. Perceptions of Kennedy’s performance led to the widespread view that his television skills won him the presidency. He even believed it himself. Scholars dispute whether Kennedy’s public charisma gave him the victory, but there’s no doubt that it changed the way campaigns were run. From then on, television was king.

Pictured: Sen. John F. Kennedy, right, and Vice President Richard Nixon, left, during the fourth Nixon-Kennedy TV debate. -

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.In 2004, George W. Bush’s re-election campaign incorporated the most effective analysis of voter data ever seen, according to Sasha Issenberg’s The Victory Lab. By measuring consumer patterns like the alcohol people drank and the car they drove, the campaign was able to target likely voters in order to persuade and motivate them. Both parties are now using these data-driven techniques to locate every last vote.

Pictured: George W. Bush holds up a baby during a campaign rally at Lancaster Airport in October 2004 in Lititz, Pa. -

Photo by Sergio Dionisio/Getty Images.

Photo by Sergio Dionisio/Getty Images.Though the 1996 election was the first one in which the presidential campaigns used the Internet, it was a novelty more than a tool until the election of 2008. The Obama campaign used social networking for voter turnout, community development fundraising and advertisements. The campaign posted thousands of videos on YouTube and at one point, Obama ads were even running within video games.

Pictured: American students celebrate the victory of President-elect Barack Obama at the Election Day Spectacular at the University of Sydney in November 2008.