The Gay Bar

Its new competition.

This series is also available as an e-book for your Kindle. Download it now.

The days—and nights—when gay bars had a monopoly on same-sex social lives are long gone. As much as contemporary queers may romanticize the gay bar as a sanctuary in a lonely world, most of us now have lots of safe spaces, both real and virtual, available to us.

Not convinced? Google "gay group" and the name of your town, and the search engine should cough up a range of organizations from sports leagues to book groups, gay churches to the local men's chorus. (I swear, half the same-sex couples who make it into the New York Times' "Vows" section claim to have met in gay hiking groups.) Over the last three decades, a clean and sober culture has developed as an alternative to the bar scene. New York's Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center hosts at least 12 regular AA meetings, as well as a dozen other 12-step recovery groups, and events like NYC Queer + Sober are designed to "provide a safe and fun experience to the sober LGBT community during Gay Pride."

When it comes to nightlife, gay revelers have more options than ever. Gay men have the circuit party scene—lavish multiday, multivenue annual events, such as the Palm Springs and Miami white parties —where the emphasis is on grand spectacle and production values that exceed anything that would be possible at a neighborhood bar. In some cities, groups use the Web to organize "guerrilla gay bars," a sort of flaming flash mob in which homosexuals descend unannounced on a straight bar and turn it gay for one night only. And in most cities, freelance promoters produce regular "parties" at straight venues as an alternative to the "gay every day" bar scene. The trend took off in the 1980s, when the community's desire for variety outpaced the supply of gay venues, and accelerated after 2000, when it became easier to publicize events via email.

Lesbian party promoters are especially busy: Even in the largest metropolis, lesbians rarely have more than one or two bars to choose from, so it's natural for women to crave new vistas. Maggie Collier, of Maggie C Events, currently runs two weekly women's parties in Manhattan. "Stiletto," on Sundays, is a daytime event at the swank Maritime Hotel, and since it's an outdoor bash, shorts and flip-flops are appropriate. On Wednesday nights at "Creme de la Femme," the code is "dress to impress." When I asked why she set that tone, she told me, "We should set the bar really high for variety. We deserve every possible option. Everything that the heterosexual nightlife community has, we ought to have those options as well."

This sort of event is not popular with gay-bar proprietors. Former owner Elaine Romagnoli told me, "They will empty your room out. Your customers will all go to that event and come back at 3 a.m., when you have an hour to go, and they're already trashed." As easy as it is to understand the bar owners' annoyance at losing their regulars to the irresistible appeal of the new and different, Collier is right when she says, "I don't think that we should stop ourselves from giving women more options just because we respect—and I definitely do—these establishments that have been around forever and that do it every night." And given the appealing economics, these regular parties are probably here to stay. Party promoters generally work on a commission basis, taking a percentage of the bar takings, so naturally their overhead is a fraction of the bars'.

Perhaps the gay bar's biggest new competitors, however, are gay dating sites and apps. "Luke," a gay man in his mid-30s, told me that new technology has been "the single most important development" in the world of gay dating. (Like some other people I interviewed for this series, he preferred not to use his real name when discussing his romantic life.) "From the time I came out in 1993 until about 1999, there was only one reliable place on a given night where you could peruse a catalog of gay men: at the bar or club. Now I have the Internet and Grindr for that."

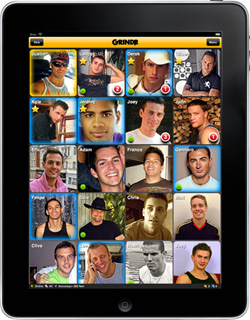

I first heard about Grindr from Irish writer Colm Toibin. At a fancy-pants New York panel on "Authors in the Age of the Internet" sponsored by the London Review of Books last April, then-55-year-old Toibin told a charming, shaggy-dog story about his adventures in gay social media. He described how he'd fantasized about a piece of technology that would marry a gay-dating service with GPS to create a device that would tell you "there's a guy if you turn left." Then he discovered that such a thing exists; it's called Grindr. Grindr is a location-based phone app that displays a grid of photographs of other members in your immediate vicinity, arranged by distance. If you like the look of someone's picture and blurb, you can chat and arrange to get together. I love the directness of the sample chat on the company website: "Hey bud I like your profile." "Thanks man. You too. Where u at?" [Sends map] "Let's meet. Here's a photo." Who said the art of seduction is dead?

Grindr launched in March 2009 and currently has more than 2 million users, one-half of them in the United States. Eight thousand guys sign up for the service every day. Grindr is strictly for Adams seeking Steves, but the company says that Project Amicus, an app for straight and lesbian users, will launch this summer.

"John," a 47-year-old D.C.-area man, has been using Grindr—along with other similar apps like Scruff—for about two years. He observed that guys in the 18-to-25 age range seem to use the app for social networking, but for older gentlemen, it's all about sex. "After all," John said, "if you're just there to meet people in a nonsexual context, why aren't you wearing a shirt in your picture?" For all his appreciation of Grindr's efficiency, John frets that it almost makes hooking up too easy: "There's very little prep work. At its basest, it's, 'Hey, I think you're hot, do you want to have sex?' 'Yeah, sure, let's do it.' "

John has never cared for bars, so Grindr hasn't replaced the gay bar for him; instead, it has provided another reason not to go there. But don't other Grindr users meet in bars once they've established that they'd like to get together? For the people I spoke with, at least, that doesn't seem to be the case. Luke, who frequently travels for work, told me that he had met Grindr dates at: "my home, his home, my hotel room, an Apple store, a bookstore, a straight hipster bar, a movie theater, and a food truck." John usually has Grindr dates come to his place, "because I'm kind of lazy." At more conventional online dating sites, people generally meet at neutral locations "so that if they find you're absolutely hideous, they're not in an awkward situation," John said. "With Grindr, there doesn't seem to be that hesitation; people seem to be more willing to just do it. That reinforces my theory that it's by and large about sex. You put pictures up; people ask for more pictures—which could be of other body parts, let's say. You supply those pictures, and that's how people make their determination about whether they'd like to meet."

John does have some qualms about Grindr: He worries that someone could set up a profile and use it to lure people to their homes for gay-bashing or robbery, though that hasn't happened to anyone he knows, perhaps because the app is still largely unknown outside the gay community. (And it should be noted that most gay people know of someone who has been physically harmed by a guy he willingly left a bar with.) When it comes to health concerns, John says that the majority of his Grindr interactions include the question, "Are you DDF?"—meaning "drug- and disease-free." Most people answer yes, though some have disclosed health issues. "I'm going to have safe sex anyway," John told me. "But it does provide some reassurance."

Location-based apps aren't just for dating. At first, Mike Atkinson of Nottingham, England was skeptical about Grindr. He told me that he was initially opposed to all forms of online dating: "I've seen many friends sucked into the vortex of [dating site] Gaydar.co.uk, wasting hours, days, weeks, and months. It seemed to me an awful lot of effort for very little reward. I mean, it's basically all about arranging a shag. It's killing gay bar culture for a particular generation. You'll find now, certainly in Nottingham, the gay scene these days is either under 25s, who like going out anyway, or over 40s, because they've always gone out. But the people in the middle think, 'Why should I go to the effort to put a nice outfit on and leave the house in the vain hope of copping off with someone, when I can just order in on Gaydar?' I think it's a terrible degradation of our community. I had Grindr bracketed in the same category."

Eventually, though, he discovered that Grindr has some alternate uses. After reading a feature in a Sunday newspaper, Mike and his civil partner Kevin downloaded the app just to see what the fuss was about. Almost immediately it led to them reconnecting with old friends—they could ignore each other in real life, but not when they showed up in the Grindr grid. "We hadn't spoken for 10 years. We fell out over something really silly and trivial. And there they were, and it seemed rude not to acknowledge each other's presence, since they only live about 300 meters away."

Several people told me that Grindr had been particularly useful when traveling, and that was certainly true when Mike went to work in the Philippines for a month. On the night he arrived, he switched on Grindr, and within an hour and a half, more than 40 men had said hello. Some of the conversations led to convivial platonic evenings, and some turned into dates. "Dates" is one of the Grindr "looking for" options, along with chat, friends, networking, and relationship, and according to Mike, date is "polite-speak for sex." (Mike and Kevin have an open relationship, though Mike told me he has since "resolved the latest midlife crisis" and isn't currently seeing other people.) At the time, Grindr only worked on iPhones, and since the only people in Manila who owned iPhones were professionals, he got to meet doctors, lawyers, and designers. Without Grindr, he would've been doomed to spending his leisure time drinking in the expat sports bar, the sole social outlet for many of his straight colleagues. Couldn't he have just gone to a gay bar? "There was a small gay scene," he told me, "but it was a half-hour cab ride away. And I'd have been standing on my own."

There's one key way that Grindr mimics the bar scene, though: Whereas online dating is a narrowing process—you can choose to see only the profiles of people whose educational achievements, income bracket, and musical tastes match your preferences—Grindr reflects the world in all its messy serendipity. It's not quite as wide open as walking into a bar, where the only "filter" is who is in the room, but Grindr's only default exclusions are proximity and age; everyone else pops up on your grid.

So maybe gay bars aren't doomed; instead they're moving into our phones.